It's the old left, many home-owning seniors, against the younger left, many renter millennials when it comes to housing, according to an NBC report that looks at the local political dynamics underpinning the expensive California housing market.

"[T]he need for more affordable housing is provoking an intense ideological struggle, and in this left-leaning state, one that pits liberals against liberals," reports James Rainey in an extensive article for NBC News on Feb. 28.

On one side are old-style liberals who lean against development and do not want to see construction cranes building high-rise apartments in their neighborhoods. On the other side are progressives who support such building efforts and focus on the effect of long commutes on the environment, particularly from cheaper exurban areas with little mass transit.

However, one not need be a millennial to take the "yes in my backyard" (YIMBY) side, as readers of Friday's post, "Debunking the Politics of Progressive NIMBYism," based on a column by the editor of the East Bay Express, would recognize. For a contrasting perspective, read "Scott Wiener’s war on local planning," in 48 Hills, a successor blog of the former alternative weekly, San Francisco Bay Guardian.

By contrast, Rainey attempts to present both sides of the debate fairly.

The Yimby newcomers, many of them millennials, have run smack into old-guard liberals, often baby-boomers or older, who cut their political teeth during an era when one could be staunchly progressive and adamantly “slow growth.” The collision has not been a happy one.

Origins of the housing debate set the stage for current tension

To his credit, Rainey provides an historical basis for the state's chronic housing shortage, beginning with the state's population growth since 1960.

For decades, California mostly left local communities to their own devices when it came to land-use planning. But in 1969, recognizing the “vital statewide importance” of providing enough housing, the state Legislature enacted a law that required each community to include a “housing element” in its general plan. [In turn, the requirement by cities to plan for housing for lower income residents per a "regional housing needs allocation" was created.]

Rainey points to the landmark law, SB 375, the Sustainable Communities and Climate Protection Act of 2008, sometimes termed anti-sprawl or smart growth due to its focus on reducing transportation emissions by reducing vehicle miles traveled (VMT) rather than by improving vehicle technology. But the law was directed at the state's 18 metropolitan planning organizations to reduce VMT, rather than the state's metropolitan cities and counties to build denser, transit-oriented housing that would reduce driving.

Housing legislation adds to tension

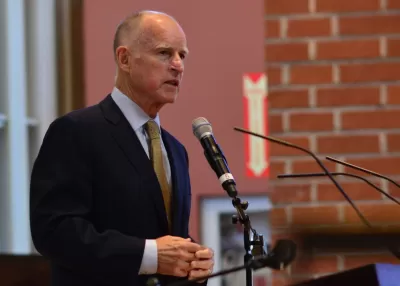

Among the 15 housing bills signed into law last year by Gov. Jerry Brown, Rainey singles out two that are contributing to tensions between state and local governments:

- SB 35, a 'by-right' housing bill by Sen. Scott Wiener (D-San Francisco) requires minesterial approval of eligible residential projects (see 11-point checklist [pdf]).

- SB 167: The Housing Accountability Act, aka "anti-NIMBY law," fines cities $10,000 per housing unit for failure to comply.

Just as housing has divided liberals in otherwise progressive California, SB 35 split the environmental community, though not unusual by itself.

"[O]ld-line liberals, including the Sierra Club, joined many city councils in saying the law does too much to help developers and takes away the long-sacrosanct right of cities and counties 'to make smart local decisions about development,' as a Sierra Club spokesperson said," writes Rainey. "But other environmental groups, like the Natural Resources Defense Council, supported the proposal."

Divisions continue with Wiener's current bill, SB 827, that mandates denser and taller zoning near transit Rainey reports that Wiener agreed to add amendments (accepted on March 1) to "ban destruction of rent-controlled units and keep in place the ability of cities to order that a certain percentage of units in new buildings be set aside for low-income tenants."

The changes make explicit that cities will retain their right to block demolitions of existing structures. When buildings are torn down, displaced tenants will have to be guaranteed equivalent housing during construction and the right to live in the new building, at their old rent.

Hat tip to Steve Birdlebough.

FULL STORY: California’s housing crunch has turned liberals against one another

Planetizen Federal Action Tracker

A weekly monitor of how Trump’s orders and actions are impacting planners and planning in America.

Restaurant Patios Were a Pandemic Win — Why Were They so Hard to Keep?

Social distancing requirements and changes in travel patterns prompted cities to pilot new uses for street and sidewalk space. Then it got complicated.

Map: Where Senate Republicans Want to Sell Your Public Lands

For public land advocates, the Senate Republicans’ proposal to sell millions of acres of public land in the West is “the biggest fight of their careers.”

Maui's Vacation Rental Debate Turns Ugly

Verbal attacks, misinformation campaigns and fistfights plague a high-stakes debate to convert thousands of vacation rentals into long-term housing.

San Francisco Suspends Traffic Calming Amidst Record Deaths

Citing “a challenging fiscal landscape,” the city will cease the program on the heels of 42 traffic deaths, including 24 pedestrians.

California Homeless Arrests, Citations Spike After Ruling

An investigation reveals that anti-homeless actions increased up to 500% after Grants Pass v. Johnson — even in cities claiming no policy change.

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.

Heyer Gruel & Associates PA

JM Goldson LLC

Custer County Colorado

City of Camden Redevelopment Agency

City of Astoria

Transportation Research & Education Center (TREC) at Portland State University

Camden Redevelopment Agency

City of Claremont

Municipality of Princeton (NJ)