New research shows that excessive vehicle travel reduces economic productivity, and that less mobility provides more productivity. Yes, you read that right.

Most transportation policies — including urban highway expenditures, off-street parking mandates, and low fuel taxes — are based on the assumption that faster, cheaper and more vehicle travel will increase economic productivity and community prosperity. It's time to critically examine that assumption. My latest research, described in The Mobility-Productivity Paradox, shows that, on the contrary, economic productivity tends to decline with more vehicle-miles and urban lane-miles, lower fuel prices, and cheaper parking.

Certainly, some motor vehicle travel is very productive. Farmers, carpenters and visiting nurses usually accomplish more by automobile than by using other modes. However, motor vehicle travel also imposes large costs to users (to own and operate vehicles), governments and businesses (for roads and parking facilities) and communities (from congestion, crash risk and pollution damages imposed on other people). As a result, as per capita driving increases, an increasing portion is economically inefficient. Its marginal costs exceed its marginal benefits. Our economy becomes more efficient if that driving is eliminated.

Let me show some of the evidence here. You can see the report for more details.

The Great Decoupling

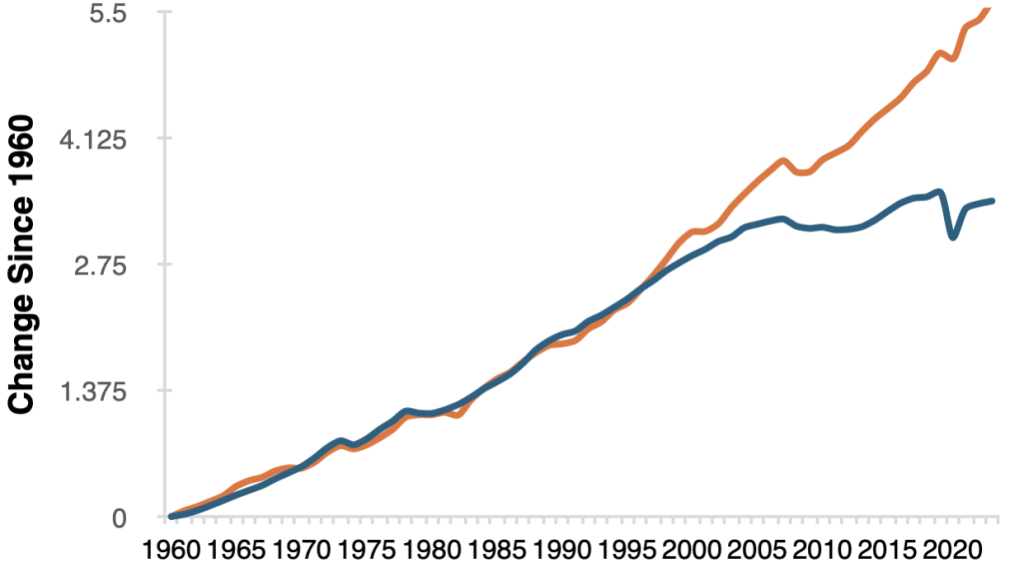

During the twentieth century, vehicle travel and economic productivity were closely aligned. But in the twenty-first century, vehicle travel peaked while productivity continued to grow and new efficiencies and technologies reduced the amount of vehicle travel required for economic activities. The following figure illustrates these trends.

U.S. Productivity and Vehicle Travel Tends (FHWA and BEA Data)

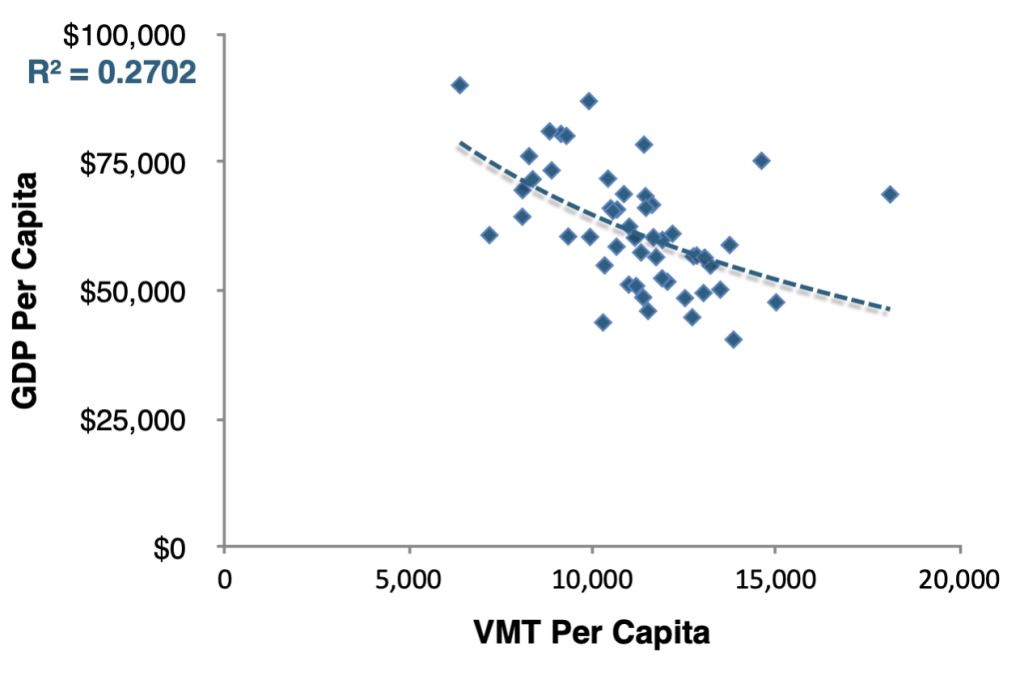

The following figure shows the negative relationship between mobility and productivity for U.S. states: productivity tends to decline as vehicle-miles increase, the opposite of what people usually assume.

Productivity and Vehicle Travel For U.S. States (FHWA 2020, PS-1)

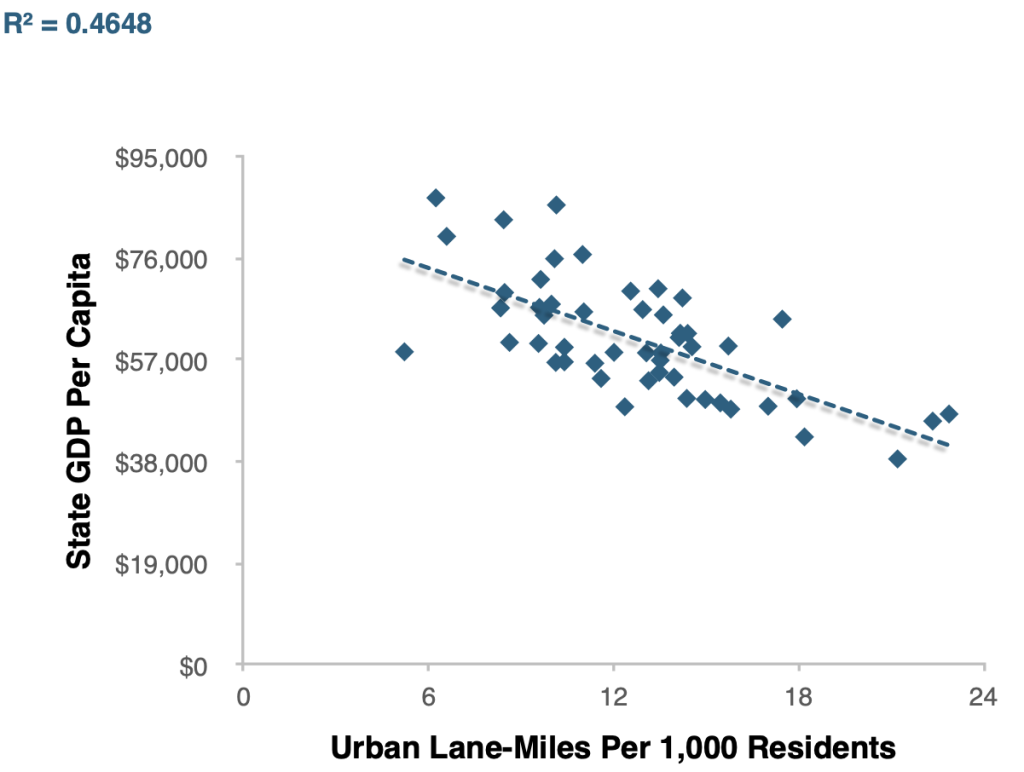

Productivity Versus Urban Lane Miles (USDOT 2024)

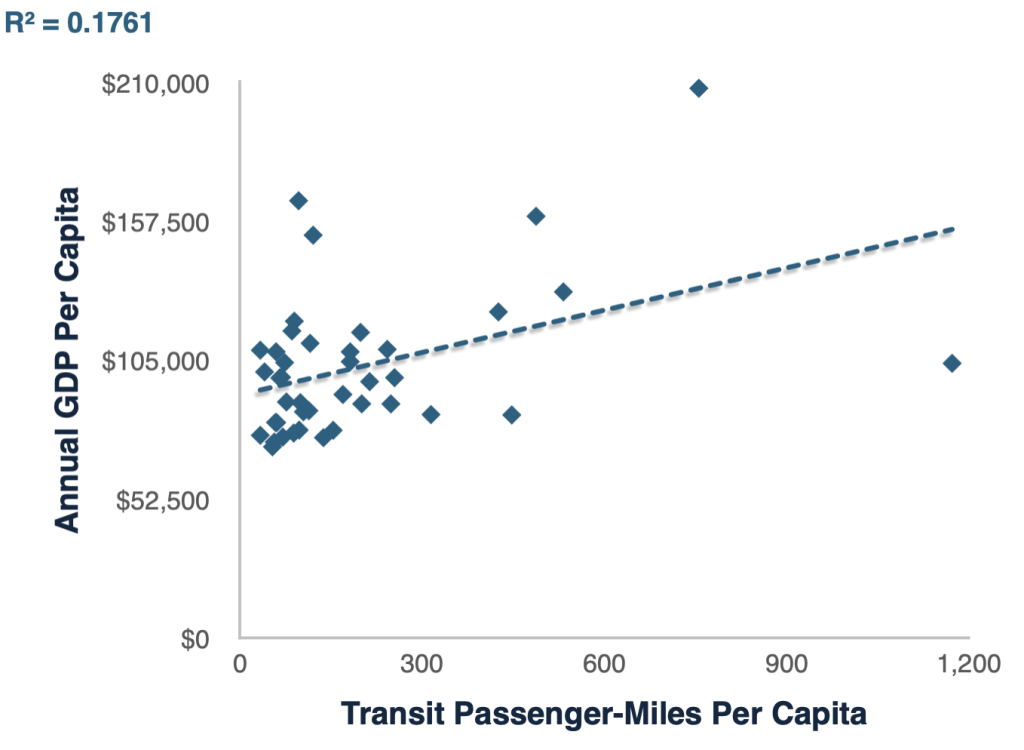

The figure below shows that regional productivity tends to increase with transit ridership. This reflects the ability of high-quality transit to increase urban transportation efficiency and encourage more compact development.

Productivity Versus Transit Ridership (APTA 2020 and BEA 2024)

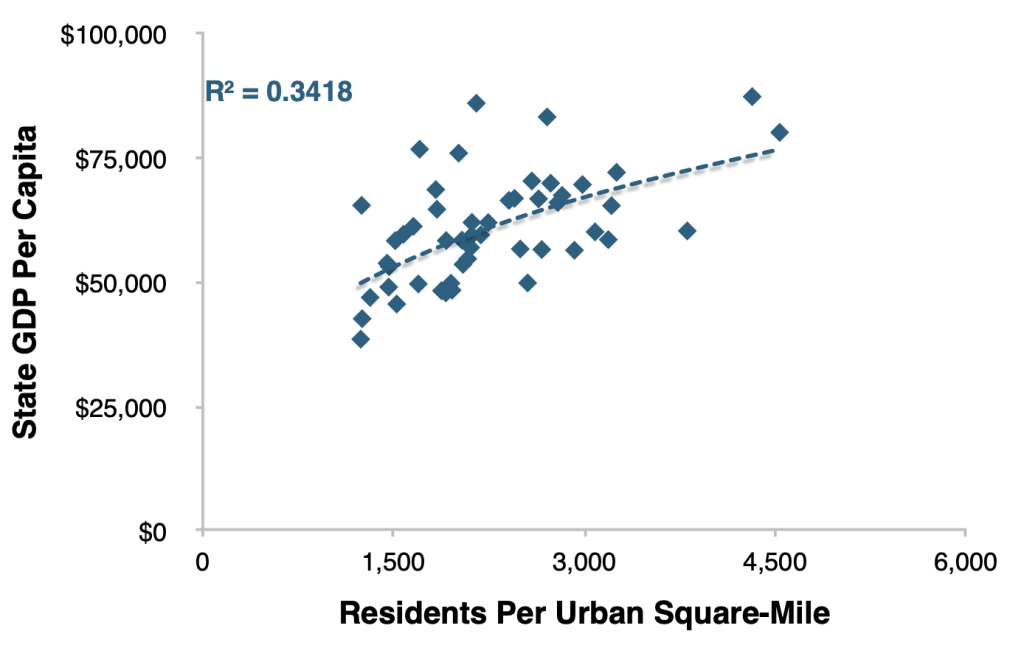

The figure below shows that productivity tends to increase with regional population density, an effect called agglomeration efficiencies. This reflects the benefits of increased proximity (reduced travel distances) and travel diversity (better non-auto travel). It indicates that policies that allow and encourage compact urban development tend to increase productivity, and those that increase sprawl are economically harmful.

Productivity Versus Urban Density (USDOT 2024)

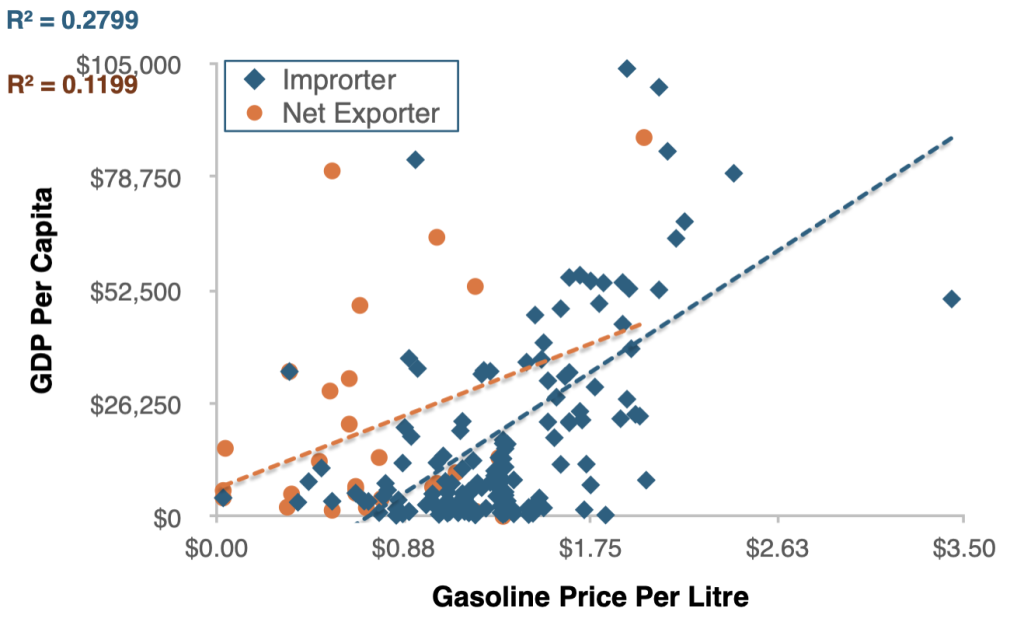

Many people assume that higher fuel prices reduce economic productivity by increasing producer and consumer costs but the relationship is actually positive; higher fuel prices are associated with more economic productivity, as illustrated in these two graphs. This suggests that by encouraging more efficient energy use and transportation, higher fuel prices help increase productivity.

National Productivity Versus Fuel Prices, Global (Global Petrol Prices 2025)

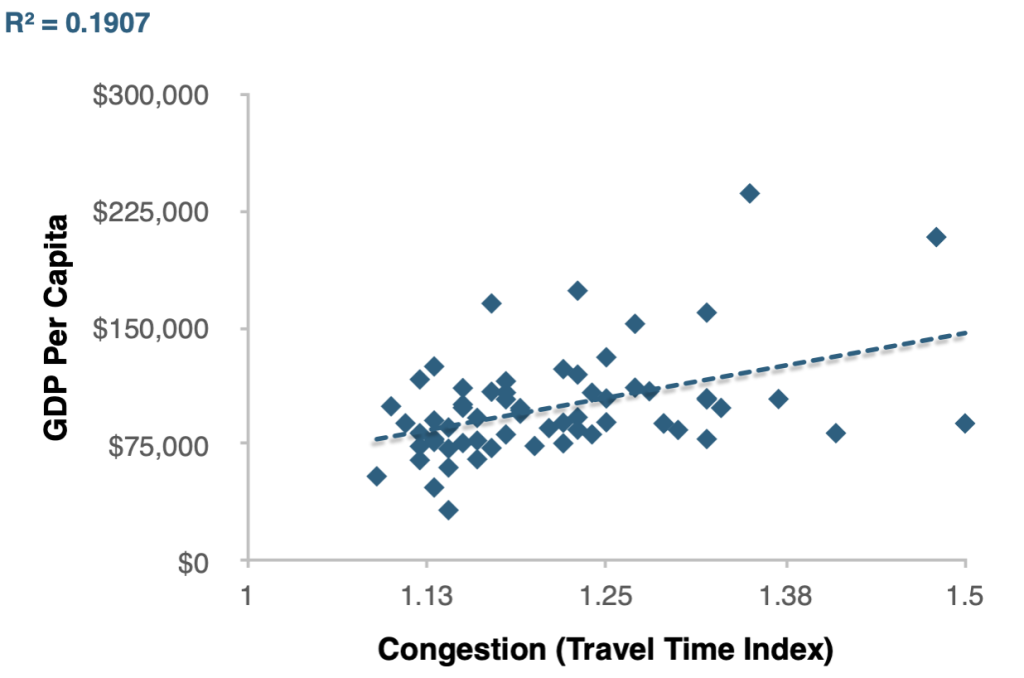

The congestion paradox

Conventional planning assumes that traffic congestion is economically harmful and urban roadway expansions increase productivity, but the figure below indicates the opposite: productivity tends to increase with congestion intensity. As previously indicated, productivity tends to decline with more urban lane-miles, indicating that efforts to reduce congestion by expanding roadways tend to be economically harmful overall; their costs exceed their benefits.

Productivity Versus Traffic Congestion (USDOT 2024 and TTI 2023)

Productivity tends to increase with urban traffic congestion. This contradicts claims that traffic congestion significantly reduces productivity. It suggests that urban roadway expansions tend to be economically harmful overall; their costs exceed their benefits.

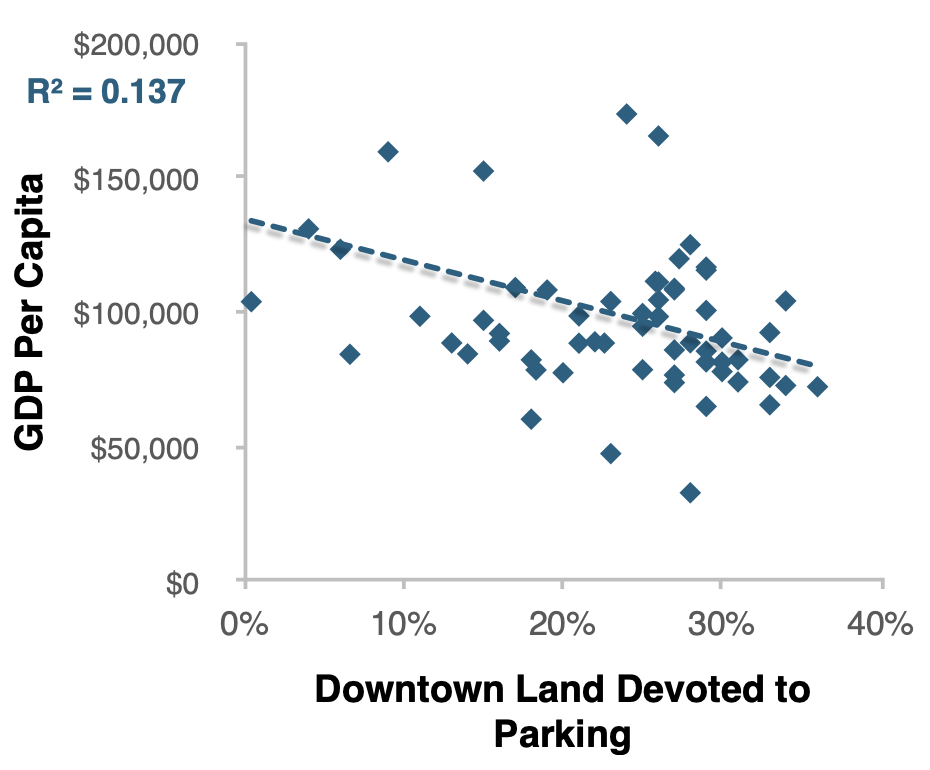

Businesses often argue that commercial districts need abundant and free parking, but productivity tends to increase with less city center parking and higher parking prices. Reducing parking supply and increasing fees can improve urban efficiency by freeing up urban land for more productive uses and encouraging more resource-efficient travel.

Productivity Versus Parking Supply and Price (PRN 2023; USDOT 2024)

In the past, businesses often assumed that motorists are better customers and workers, so assumed that improving automobile travel supports economic development. This research indicates otherwise. Many cities are attracting economically successful residents who prefer non-auto travel and want less vehicle traffic. More compact and multimodal urban neighborhoods tend to attract more residents, customers, and workers by increasing development density and mix, improving multimodal accessibility, reducing vehicle traffic and reducing infrastructure costs. For example, in auto-dependent areas where most customers and workers drive, parking subsidies represent about 20 percent of rents; in multimodal areas where only half drive, rents can decline about 10 percent, and the pool of potential workers increases 10-30 percent, consisting of potential workers who cannot drive.

As a result of these savings and benefits, productivity, business activity and property values tend to increase with Walk Scores, proximity to transit, complete streets, and bikeways.

Explaining the paradox

My research identifies ways that increased vehicle travel can reduce economic productivity, as summarized in the table below.

Summary of Ways that Vehicle Travel Can Reduce Productivity

Factor |

Effects on Productivity |

Accessibility Impacts |

|

User costs |

Households spend less on other goods, including education and housing that increase future productivity. |

Reduces access to economic opportunities such as jobs, particularly for lower-income people. |

|

Infrastructure costs |

Vehicle infrastructure subsidies increase taxes, rents and the costs of other goods. |

Wider roads and larger parking lots degrade walking and bicycling. |

|

External costs |

Vehicle traffic causes congestion, crashes and pollution that reduces productivity. |

Congestion delays cars and buses. Risk and pollution degrade active travel. |

|

Reduced non-auto mobility options |

Reduces non-drivers’ economic opportunities and increases chauffeuring costs. |

Reduces non-auto accessibility. |

|

Sprawl-related costs |

Increases travel and public service costs, and reduces agglomeration efficiencies. |

Reduces accessibility, particularly for non-auto modes. |

|

Less productive expenditures |

Vehicle and fuel purchases generate fewer local jobs and less business activity than most other expenditures. |

Sprawl encourages regional shopping, reducing local services and jobs. |

|

Neighborhood attractiveness |

Heavy traffic and ugly parking lots make an area less attractive to residents and customers. |

Wider roads and increased traffic degrade walking and bicycling access and transit efficiency. |

This table summarizes ways that vehicle travel can reduce productivity and accessibility.

This indicates that increased motor vehicle travel tends to reduce productivity by increasing costs, reducing accessibility, and making neighborhoods less attractive to residents, customers and workers. These impacts can be large. For example, compared with a compact, multimodal community, automobile dependency and sprawl add many thousands of dollars in annual user, infrastructure and external costs and, by increasing trip distances and chauffeuring burdens, add hundreds of hours in additional annual travel times. Similarly, in automobile-dependent areas businesses must subsidize customer and employee parking, have fewer potential customers and workers (those who cannot drive), and operate in less attractive environments. More compact, multimodal communities provide savings and benefits that filter through the economy, increasing productivity, affordability, economic opportunity, property values and tax revenues.

This research suggests that optimal vehicle travel is about 4,000 annual vehicle-miles per capita and 50 percent auto mode shares, more in rural areas and less in cities and lower-income areas. Interestingly, recent research finds that Americans who rely on driving for more than 50 percent of their out-of-home trips tend to have decreased life satisfaction: too much driving is bad for your happiness as well as your wallet.

Finding balance

It's time to question assumptions about the ways that transportation policies affect economic development. Transportation agencies spend many tens of billions of dollars every year to expand urban roadways based on the assumption that will reduce congestion delays, which will save travel time, which will make workers more productive, which will increase community wealth, which will make everybody happier. Forget those assumptions; they are unjustified.

This research indicates that urbanization improves accessibility, reduces costs, and provides agglomeration efficiencies. Policies that support urbanization increase economic productivity and opportunity; those that contradict urbanization are economically harmful. This is not to suggest that economic productivity requires everybody to live car-free in high rise apartments. On the contrary, some of the largest benefits appear to result from moderate reductions in vehicle miles travelled and small increases in non-auto mode shares, from households owning one rather than two cars, and from moderate increases in density.

Mobility is like salt in cooking — you want some, but not too much. This research indicates that the best economic development strategy is to improve transportation efficiency so economic activities needs less vehicle travel. This requires a diverse transportation system to accommodate diverse travel demands, plus policies that favor higher-value trips and space-efficient modes over lower-value trips and space-intensive modes. This can be achieved with multimodal planning and incentives for travellers to choose the best option for each trip — walking and bicycling for local errands, transit when travelling on busy corridors, and driving when it is truly optimal — plus development policies that create compact communities. This also helps achieve many goals, including affordability, equity, health and safety and environmental quality.

Planetizen Federal Action Tracker

A weekly monitor of how Trump’s orders and actions are impacting planners and planning in America.

Map: Where Senate Republicans Want to Sell Your Public Lands

For public land advocates, the Senate Republicans’ proposal to sell millions of acres of public land in the West is “the biggest fight of their careers.”

Atlanta Bus System Redesign Will Nearly Triple Access

MARTA's Next Gen Bus Network will retool over 100 bus routes, expand frequent service.

Platform Pilsner: Vancouver Transit Agency Releases... a Beer?

TransLink will receive a portion of every sale of the four-pack.

Toronto Weighs Cheaper Transit, Parking Hikes for Major Events

Special event rates would take effect during large festivals, sports games and concerts to ‘discourage driving, manage congestion and free up space for transit.”

Berlin to Consider Car-Free Zone Larger Than Manhattan

The area bound by the 22-mile Ringbahn would still allow 12 uses of a private automobile per year per person, and several other exemptions.

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.

Heyer Gruel & Associates PA

JM Goldson LLC

Custer County Colorado

City of Camden Redevelopment Agency

City of Astoria

Transportation Research & Education Center (TREC) at Portland State University

Camden Redevelopment Agency

City of Claremont

Municipality of Princeton (NJ)