Remaking streets into attractive and successful places can be a challenge. But following a few straightforward checklists can simplify the process. Amber Hawkes and Georgia Sheridan guide the way, in this final article in their series on Remaking the Streetspace.

Our series on Rethinking the Streetspace has discussed the changing perception of the role of the streetspace and the steps cities are taking to regulate streets more sensitively. This final article presents a checklist of considerations for cities and stakeholders who are undergoing the process of creating new street design approaches, policies, and manuals.

Our series on Rethinking the Streetspace has discussed the changing perception of the role of the streetspace and the steps cities are taking to regulate streets more sensitively. This final article presents a checklist of considerations for cities and stakeholders who are undergoing the process of creating new street design approaches, policies, and manuals.

When re-conceptualizing approaches to street design, municipalities need to be mindful of both process-related and content-relatedconsiderations. While "process-related" refers to the "how" - the collaboration, the methodology, and the means by which new manuals and policies come into practice, "content-related" refers to the "what" - the themes, the materials, and the content within the policies and manuals themselves.

Process-Related Checklist:

- Find a Strong Leader or Voice

Having a strong leader whose voice can motivate agencies to move forward collectively and who can articulate a clear vision is a key component of the process, which was emphasized by of the planners with whom we spoke. Political muscle and high-level vision is necessary to establish a unifying agenda among distinct departments, agencies, and stakeholders.

- Determine Time, Staff, and Funding

Consider your timeframe for completion, staff availability, staff skill sets, openness to using an outside consultant, and funding sources. San Francisco was able to bring money together from various agencies (including Metro Transit Authority, Public Works, Public Utilities Commission) to fund the Better Streets Plan, using consultants to help city staff complete the draft plan within a year.

- Set an Inter-Disciplinary Vision and Agenda

Begin inter-disciplinary coordination early on at the goal setting stage wherein various departments involved in the design, operations, and maintenance of the streetspace set a common agenda. As Emily Gabel-Luddy and Simon Pastucha, Urban Designers from the City of Los Angeles Urban Design Studio described, creating new street design approaches not only involves new ideas for the streetspace itself, but also a "new culture at City Hall" to coordinate separate departments. Setting the agenda may involve unweaving deeply entrenched decision-making patterns. At times, it can feel like shifting a tanker.

- Understand the Larger Policy Framework

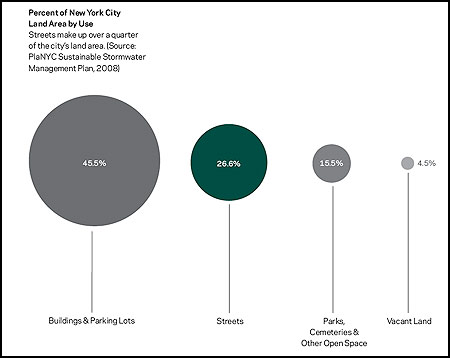

Review your overarching planning documents to identify supportive planning policies that will give the street design manual both legal and political support. San Francisco's "Better Street's Plan" was assisted by the City's "Transit First" policy, which was legislated. New York City has few legislative requirements related to street design, but does have the force of PlaNYC, a document developed by Mayor Bloomberg that outlines the City's long-term infrastructure and sustainability plan, explained Michael Flynn, Director of Capital Planning for New York City's Department of Transportation. To ensure new street design standards would be supported by the city's transit policies, the City of Seattle rewrote their Strategic Transportation Plan to help set the agenda for multi-modal, multi-purpose streets before beginning their street design manual. Staff also reviewed the City's Comprehensive Plan to understand if the abstract goals could be translated into political will to move forward with street design improvements. Similarly, Los Angeles Planners developed a set of Citywide Urban Design Principles simultaneous to the preparation of new Street Standards to ensure that design principles support a new design approach in the public right-of-way.

- Identify and Address Key Issues and Obstacles

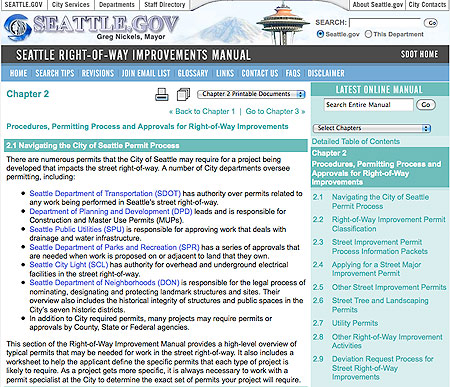

Identify regulatory barriers in the application and approval process that may slow or prevent new street standards from being implemented. For example, before developing the Right-of-Way- Improvements Manual, Barbara Gray from the City of Seattle Department of Transportation, interviewed staff from various departments to pinpoint regulatory impediments. Based on interviews, she wrote a series of issue papers that were presented to management staff during inter-department meetings. The issue papers highlighted problems that some departments were not aware of, and identified policy areas where greater discussion and inter-department coordination was needed. For example, an issue paper on natural drainage led to a discussion and formal agreement between the Department of Transportation, which agreed to manage grey water, and Public Utilities, which agreed to maintain green infrastructure. Getting into the nitty-gritty early on helps streamline the implementation process since agreements about infrastructure, operations, and maintenance had already been reached.

- Define the Regulatory Framework

Understand how the new street standards and designs will fit within current codes and policies. How the new policies will relate to existing codes and regulations helps shape the public engagement process and the staff advisory process. A looser, more conceptual plan will require less vetting and inter-department coordination than one that is adopted as code and used as a legally-binding document.

- Determine the Level of Community Engagement

Discuss the level of community engagement needed. This can depend on several things: timeframe for project completion, resources, political support, staff enthusiasm, and the culture of engagement within the community. Timing is also key. New York developed its Street Design Manual on a fast timeline with input mainly from government agencies and outside technical reviewers, with the expectation that the Manual's release would kick off a wider dialogue with all public and private stakeholders that would inform future updates to the relatively flexible document. On the other hand, San Francisco, a liberal city known for its vocal citizenry, has held numerous community meetings at various stages of the process for feedback, made possible, in part by a large project team, relative to some other cities.

- Coordinate a Decision-Making Team

Outline the decision-making team and its roles. One of the most critical parts of the process is creating multi-disciplinary teams for inter-agency collaboration. Deciding who is on the decision-making team should be based on the intended users of the new policies and manual. Seattle created a Management Team, a Staff Team, and an external Advisory Group composed primarily of developers and contractors. The Staff Team drafted the manual's original content, which was revised by the Management Team and vetted by external Advisory Group, then sent back to the staff team for changes- an iterative process. Similarly, San Francisco created a Policy Group Team, composed of the Directors from different departments to make decisions when the inter-department Staff Team, who met bi-monthly, could not agree. Public input was addressed by a Citizen Advisory Committee of 15 community members (including landscape architects, transportation professionals, and at-large community stakeholders) who met with staff throughout the development process. In Los Angeles, the Downtown Design Guide helped create a new decision-making model for development in the City, in which Planning, Transportation, Engineering, and the Redevelopment Agency meet together to review new development projects in Downtown. During the meeting, each department can give input on the design of the project and how it supports the mission of their respective departments. As important as developing inter-agency relationships is cultivating them among junior staff so that a culture of collaborative decision-making is nurtured over time as passed on to the next generation of planners.

- Train Staff

Provide staff with ample training to feel comfortable with new materials and techniques. Simon Pastucha (Los Angeles) explained that staff comfort levels are critical in avoiding "fear-based planning"; staff need to hear that new goals and principles are also being articulated by their managers. They also need examples of where things have worked and why the city is embarking on a new approach so that they are armed with information when people ask them questions.

- Remember the User

Create an easy-to-use format and monitor how it is being applied. Seattle, one of the earliest cities to begin rethinking their streetspace in the 1990s, created a successful web portal, cited by many of the Planners with whom we spoke, which was tested and evaluated through user surveys to ensure ease of use. LA has linked the Downtown Design Guide to an accessible City website in the Engineering Bureau called 'NavigateLA' where the user can navigate through a map of Downtown streets, click on the relevant centerline, and view new street standards.

- Educate, Advocate, and Publicize

Share the manual with the public through workshops, press releases, and articles. Public perception is critical in how people will accept new approaches. Don't underestimate the power of publicity.

- Talk to Other Cities as Resources

Pick up the phone, read other manuals, check out city websites. Share your stories and ask other planners for lessons learned.

Content-Related Checklist:

- Include Incremental Changes That Can Happen Quickly

Identify small, visible projects that can have immediate effects. Creating visual indicators of change helps building community awareness and support for larger policy initiatives. Small projects build confidence within the community who can literally see that change is possible. Both New York and San Francisco have created "pop-up" plazas with inexpensive street furniture and planters for temporary landscaping.

- Identify Strategies That are Appropriate for Your City

Capitalize on your city's assets and methods; every city has its own tested approaches to implementing new policy initiatives. Seattle is famous for its pilot projects and has used various pilot programs to test out street design recommendations that later became standards. Los Angeles, a city of many different neighborhoods, decided to take a macro approach to urban design before delving into the specifics. The Los Angeles Urban Design Studio developed a set of overarching design principles, rather than specific design strategies.

- Think About an Appropriate Level of Flexibility

Consider what city operations in the streetspace require uniformity for safe and successful functioning and what operations might benefit from more context-sensitive design. Make a document that can change over time and celebrate the concept of a "work in progress," allowing for user feedback and changing materials and technologies to help update the street design manual. Pilot projects are a great way to test out new techniques before making them standard. As the New York Street Design Manual explains, "specific treatments may be added, updated or removed, as appropriate, over time."

- Link Concepts with Tools and Graphics

Provide design tools and graphics, not just concepts and narrative. It is useful to add simple, clear graphics to help explain engineering standards as well as more abstract design issues such as "maintaining a human scale", "creating street enclosure", or "improving texture and color." The City of New York's Street Design Manual is especially easy to navigate and understand, using photos as examples to describe key concepts, along with simple text. Consider creating a toolkit of options so that planners and designers understand the multiple approaches that they can use to arrive at desired goals. Someone should be able to pick up the manual and understand its intent and strategies with a brief read through, rather than a detailed study of the entire document.

- Don't Forget the Buildings

Consider regulating the street edge in addition to the streetspace. Many street design manuals create grand visions for the streetspace that stop at the street edge, where the building meets the sidewalk. Great streets rely on a complementary relationship between the public and private realm. Los Angeles' Downtown Design Guidelines, for example, incorporate the design of building frontages, scale, and massing into its discussion and guidelines for great streets.

- Delegate Operations and Maintenance

Explain who is responsible for construction, maintenance, and operations. Great streets require upkeep. Create a flow chart of agencies involved in the streetspace. Describe who does what and how, outline funding streams to streamline the planning process. This step is dependent on understanding how new street manuals fit into a city's regulatory framework.

- Include Indicators of Success

Assign related indicators of success to new policies for the streetspace to determine how well the new standards are functioning. Defining indicators of success and crafting a methodology to examine successes and failures will help create accountability.

- Explain Ties to the Bigger Picture

Help build the argument for "Why Design Matters" by describing how your manual fits with in the larger movement to rethink the streetspace. Building public awareness and support in one city helps increase attention and understanding at the local, regional, and federal level, in terms of policy and funding.

Amber Hawkes and Georgia Sheridan are Urban Planners and Designers working in Downtown Los Angeles at Torti Gallas and Partners. They have lectured at conferences and universities and have worked in a variety of capacities that inform their planning and design work, from behavioral art therapy, social work, and historic preservation, to health law policy, green building policy, and journalism.

This article is part of a four-part series looking at street design and policy. The first part of this series looks at why street design matters and where we are today in terms of designing the "street space." The second part of this series review the history of street design and look to the future. The third part reviews street design manuals and toolkits.

Planetizen Federal Action Tracker

A weekly monitor of how Trump’s orders and actions are impacting planners and planning in America.

Map: Where Senate Republicans Want to Sell Your Public Lands

For public land advocates, the Senate Republicans’ proposal to sell millions of acres of public land in the West is “the biggest fight of their careers.”

Restaurant Patios Were a Pandemic Win — Why Were They so Hard to Keep?

Social distancing requirements and changes in travel patterns prompted cities to pilot new uses for street and sidewalk space. Then it got complicated.

Platform Pilsner: Vancouver Transit Agency Releases... a Beer?

TransLink will receive a portion of every sale of the four-pack.

Toronto Weighs Cheaper Transit, Parking Hikes for Major Events

Special event rates would take effect during large festivals, sports games and concerts to ‘discourage driving, manage congestion and free up space for transit.”

Berlin to Consider Car-Free Zone Larger Than Manhattan

The area bound by the 22-mile Ringbahn would still allow 12 uses of a private automobile per year per person, and several other exemptions.

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.

Heyer Gruel & Associates PA

JM Goldson LLC

Custer County Colorado

City of Camden Redevelopment Agency

City of Astoria

Transportation Research & Education Center (TREC) at Portland State University

Camden Redevelopment Agency

City of Claremont

Municipality of Princeton (NJ)