To support equity goals, planners must accommodate diverse ideological perspectives, including political environments that focus on functional fairness rather than demographic categories.

Greetings from the city of Baltimore, where I’ve spent the last few days at the TRB Conference on Advancing Transportation Equity. It was worth the substantial time and money costs; I’ve enjoyed seeing old friends and making new ones, and having many productive discussions that would not be possible with online conferences.

I am passionate about this subject. I’ve been working on transportation equity research for decades, I’ve been a member of TRB committees related to transportation justice and equity, and my reports, Evaluating Transportation Equity and Fair Share Transportation Planning, are widely cited by peers.

The presentation I gave yesterday, titled Fair Share Transportation Planning and Funding, examines ways that current planning prioritizes speed over other community goals, and so favors automobile travel over slower but more affordable, inclusive, and resource-efficient modes. (Here is a slideshow for a presentation I gave on the subject at a conference earlier this year.) Those planning practices are inherently unfair to people who cannot, should not, or prefer not to drive, and are therefore regressive (they harm lower-income households).

This perspective was exceptional. The other four presentations at the session, and most discussions at the conference, focused on social justice, addressing the needs of specific disadvantaged groups such as racial and gender minorities. It may be time for advocates and practitioners to give more attention to horizontal and less to vertical equity analysis, particularly if they are working in a politically conservative environment. Let me explain.

The table below summarizes my equity analysis schemata. It identifies five main types of transportation equity analysis. The first two are horizontal, meaning they assume that people who are considered similar in need and ability should be treated similarly, while three are vertical, meaning they assume that public policies should favor disadvantaged groups.

Types of Transportation Equity Analysis

Type |

Description |

|

Horizontal |

Similar people should be treated similarly |

|

Fair Share |

Each person receives a fair share of public resources. |

|

External costs |

Travellers minimize the costs they imposed on others. |

|

Vertical |

Public policies should favor disadvantaged groups |

|

Inclusivity |

Ensure that everybody enjoys basic mobility and accessibility. Reduce mobility disparities. |

|

Affordability |

Lower-income households can afford basic mobility. Provide affordable travel options. |

|

Social Justice |

Everybody is treated with fairness and dignity. Past injustices are corrected. |

There are various ways to evaluate transportation equity. Comprehensive analysis should consider all of these impacts and respond to community priorities.

In general, ideologically conservative people tend to focus on horizontal equity (everybody should be treated equally) while those who are ideologically progressive tend to focus on vertical equity (public policies should favor disadvantaged groups). These are not mutually exclusive — it is unnecessary to choose one approach over others — because they often overlap. In particular, policies and planning practices that favor auto over non-auto travel are both unfair (horizontally inequitable) and unjust (vertically inequitable).

I believe that transportation equity analysis should be comprehensive: all five impacts should be considered, and the results should be tailored to the context. For example, in ideologically progressive jurisdictions the analysis can lead with vertical equity analysis, examining how policies affect disadvantaged groups, while in ideologically conservative jurisdictions the analysis can lead with horizontal equity, identifying biases that unintentionally favor more exclusive and expensive modes, and therefore drivers over non-drivers, and higher income over lower-income travelers.

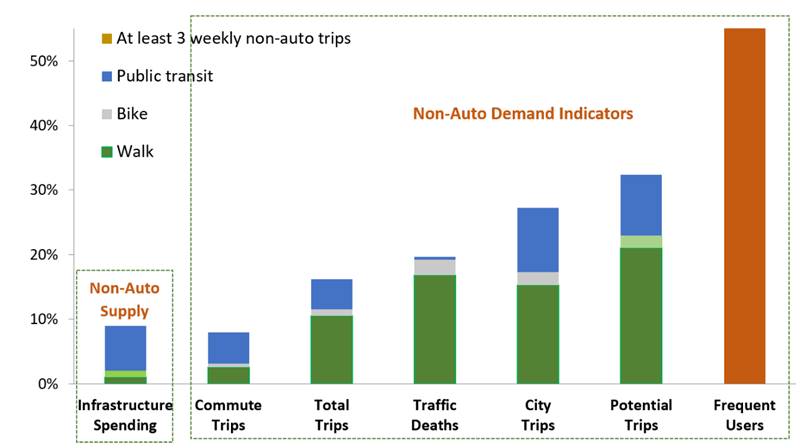

More multimodal planning and funding are justified for fairness and economic efficiency sake. My research indicates that in typical North American communities, less than 10 percent of transportation infrastructure spending is devoted to non-auto infrastructure (sidewalks, bikeways, and public transit subsidies), which is significantly less than non-auto mode shares (15 percent), the portion of non-auto traffic deaths (20 percent), or the portion of travelers who cannot, should not, or prefer not to drive and will use non-auto modes if they are convenient, comfortable, and affordable.

Non-Auto Spending Versus Demand Indicators

In general, progressives tend to support programmatic solutions that provide special support for specific disadvantaged groups. Conservatives tend to support policy reforms that respond to specific functional conditions such as mobility impairments, low incomes, and access to economic opportunities.

Below are perspectives and arguments that can be used to support more equitable planning outcomes in a politically conservative community:

- Basic mobility, and therefore more inclusive and affordable transportation planning, is critical to allow people, including those with disabilities and low incomes, to access education, employment, and other economic opportunities. It is a hand-up, not a handout.

- Improving non-auto access expands the pool of potential employees and customers available to businesses, supporting economic opportunity to disadvantaged workers and economic development to communities.

- Improving and encouraging non-auto modes is often the most cost-effective way to reduce traffic congestion and parking problems, and therefore helps governments and businesses save money on road and parking infrastructure.

- Improving active modes improves public fitness and health, addressing health problems such as obesity and diabetes that plague many politically conservative regions.

- Improving non-auto modes can be an effective traffic safety strategy. Traffic safety strategies such as graduated driver’s licenses, special senior driver testing, and anti-impaired driving campaigns become more effective and politically acceptable if matched with improved travel options for youths, seniors, and drinkers.

- Surveys indicate that many households want to live in walkable neighborhoods, and many travelers would prefer to drive less and rely more on non-auto modes, provided that those options are convenient and affordable. The principle of consumer sovereignty requires that public policies respond to those preferences, for example, by improving walking conditions, increasing allowable densities and eliminating parking minimums in walkable neighborhoods.

- More efficient transportation and parking management can reduce impervious surface area and therefore stormwater management costs.

Planners have a responsibility to respond to community needs. Regardless of what happens in this year’s federal election, we should develop more equitable and responsive transportation policies that can gain support in any jurisdiction regardless of its political ideology.

For more information

Kristin N. Agnello (2018), Zero to 100: Planning for an Aging Population, Plassurban.

America Walks Mobility Justice Resources provides various information on transportation social justice issues.

Samikchhya Bhusal, Evelyn Blumenberg and Madeline Brozen (2021), Access to Opportunities Primer, UCLA Institute of Transportation Studies.

Ralph Buehler and Andra Hamre (2015), “The Multimodal Majority? Driving, Walking, Cycling, and Public Transportation Use Among American Adults,” Transportation 42, 1081–1101.

Felix Creutzig, et al. (2020), “Fair Street Space Allocation: Ethical Principles and Empirical Insights,” Transport Reviews (DOI: 10.1080/01441647.2020.1762795).

Fie Li and Christopher Kajetan Wyczalkowski (2023), “How Buses Alleviate Unemployment and Poverty: Lessons from a Natural Experiment in Clayton County, GA,” Urban Studies.

Todd Litman (2022), “Evaluating Transportation Equity: Guidance for Incorporating Distributional Impacts in Transport Planning,” ITE Journal, Vo. 92/4, April.

Todd Litman (2023), Transportation Market Distortions: A Survey, Victoria Transport Policy Institute.

Todd Litman (2024), Fair Share Transportation Planning, Victoria Transport Policy Institute.

Opportunity Atlas measures economic opportunity for U.S. communities based on average incomes, rents and employment rates.

Transport Equity Analysis is a European Union program to provide practical guidelines for assessing the equity impacts of transportation projects and policies.

Maui's Vacation Rental Debate Turns Ugly

Verbal attacks, misinformation campaigns and fistfights plague a high-stakes debate to convert thousands of vacation rentals into long-term housing.

Planetizen Federal Action Tracker

A weekly monitor of how Trump’s orders and actions are impacting planners and planning in America.

In Urban Planning, AI Prompting Could be the New Design Thinking

Creativity has long been key to great urban design. What if we see AI as our new creative partner?

King County Supportive Housing Program Offers Hope for Unhoused Residents

The county is taking a ‘Housing First’ approach that prioritizes getting people into housing, then offering wraparound supportive services.

Researchers Use AI to Get Clearer Picture of US Housing

Analysts are using artificial intelligence to supercharge their research by allowing them to comb through data faster. Though these AI tools can be error prone, they save time and housing researchers are optimistic about the future.

Making Shared Micromobility More Inclusive

Cities and shared mobility system operators can do more to include people with disabilities in planning and operations, per a new report.

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.

planning NEXT

Appalachian Highlands Housing Partners

Mpact (founded as Rail~Volution)

City of Camden Redevelopment Agency

City of Astoria

City of Portland

City of Laramie