Let's rely on science, not ideology and propaganda, when planning solutions to urban unaffordability. Look for credible evidence in the peer-reviewed publications referenced here.

Few issues cause more blood to boil than debates about the causes and solutions to housing unaffordability. On this issue, many people lead with their opinions followed by whatever evidence they can muster. The results can get ugly, particularly for those of us who prefer information to be credible.

My latest column, "A Critical Review of 'Sick City: Disease, Race, Inequality and Urban Land'" included a critique of Professor Patrick M. Condon's article, "Density, Affordability, & The 'Hungry Dogs' of Land Price Speculation," published in The Planning Report, a Los Angeles-based trade publication. I contacted the editor-in-chief, David Abel, to discuss my counterpoint to Condon's article.

In response, Mr. Abel sent links to Planning Report interviews of leading supply skeptics, including "UCLA’s Michael Storper on Squaring Urbanism & Density" and "Exporting California's Housing Challenges? Michael Storper & Patrick Condon Correct the Record on Out-Migration."

In my view, these articles present a narrow perspective and lack critical analysis, thus raising an epistemological question: How should we evaluate research quality in the field of planning and urban development?

Of course, everybody is entitled to their own opinions, but not their own facts. Some publications are little more than propaganda—information presented only if it supports a predetermined conclusion. Good planning requires comprehensive, objective, accurate, and transparent information that allows policy-makers, practitioners, and the general public to make informed decisions. Here are a few rules to help evaluate research quality:

- It should have a well-defined research question.

- It should include a review of previous related research.

- Data sources and analysis should be clear and available for review.

- It should discuss critical assumptions, potential biases and omissions, contrary findings, and alternative interpretations.

- It should be peer reviewed.

- It should acknowledge and respond to legitimate criticism.

Let's evaluate the quality of research used by proponents of various housing policy ideologies.

Housing Policy Ideologies

There are three main housing policy ideologies: free market proponents, planning experts, and supply skeptics. Let's examine the quality of their evidence.

Free Market Proponents

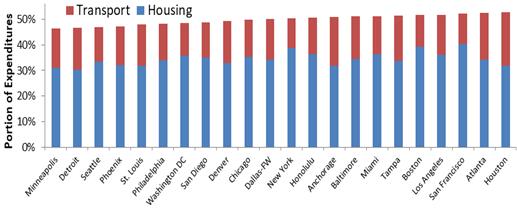

Free market proponents such as The Heritage Foundation, Joel Kotkin, and Wendell Cox blame housing unaffordability on regulations that limit urban expansion and therefore the construction of single-family housing. As evidence, they point to International Housing Affordability Survey data showing lower housing prices in sprawling cities such as Houston and Atlanta compared with more compact cities like New York and San Francisco. However, as discussed in my column, "True Affordability: Critiquing the International Housing Affordability Survey" and my more detailed critique, that report is incomplete and biased. The study appears to oversample single-family housing (we can't be sure because the analysis is not transparent), which exaggerates unaffordability in compact cities where a large portion of lower-priced housing is multifamily. It also ignores other costs besides houses prices, such as utility and transportation expenses. When these costs are considered, compact, multimodal cities such as Minneapolis, Seattle, and Philadelphia turn out to be more affordable overall than sprawled, automobile-dependent cities such as Atlanta and Houston, as illustrated below.

Free market advocates also tend to misrepresent consumer demands and land use restrictions. They assume that almost all households want to live in single-family houses in automobile-dependent suburbs, although housing preference surveys indicate that a growing majority of households want to live in mixed-use, walkable urban neighborhood and lead multimodal lifestyles. They also assume that anti-sprawl restrictions are common and the primary cause of housing price increases, but as Michael Lewyn and Kristoffer Jackson demonstrate in "How Often Do Cities Mandate Smart Growth or Green Building?" such regulations are actually uncommon and weak, while regulations limiting affordable infill are extremely common.

The Quality of Their Evidence

Free market advocates tend to publish through pro-market, industry-supported think tanks that have low standards of evidence. They seldom publish in peer reviewed journals. My critiques of their publications, such as "Evaluating Criticism of Smart Growth," "True Affordability: Critiquing the International Housing Affordability Survey," and "Response to Putting People First," identify substantial omissions, biases and errors in their analysis, which they seldom acknowledge or correct. They ignore evidence concerning various costs of sprawl including high transportation costs, increased housing foreclosure rates, and reduced economic mobility (i.e., the opportunity for children to become more economically successful than their parents).

Housing Experts

Most housing experts that I work with take a nuanced view of housing unaffordability problems and solutions. We define housing problems broadly to include homelessness, the problems facing low-income households (first income quintile, who are mostly renters), and the lack of affordable housing options for moderate-income households (second and third income quintile) in high-accessibility, high-opportunity neighborhoods. We consider total housing and transportation costs when evaluating affordability.

We support reforms to allow developers to build more affordable housing types (e.g., multiplexes, townhouses, and mid-rise multifamily) with unbundled parking (parking rented separately from housing, so car-free households are no longer forced to pay for costly parking spaces they don't need) in walkable urban neighborhoods, including large-scale upzoning, eliminating parking minimums, reducing development fees and approval requirements for moderate-priced infill, plus subsidizing housing for families with special needs.

Most planners also support innovative home ownership models, such as housing cooperatives and co-housing, modest inclusivity requirements (not so high that they reduce housing production), subsidies for households with special needs such as disabilities and very low incomes, and, sometimes, special regulations such as rent controls to limit rent increases.

The Quality of Their Evidence

An extensive body of peer-reviewed research supports planning experts' position. This evidence is summarized in a recent report by professors Shane Phillips, Michael Manville, and Michael Lens, "Research Roundup: The Effect of Market-Rate Development on Neighborhood Rents," and discussed in several of my previous columns including "A Critical Review of 'Sick City: Disease, Race, Inequality and Urban Land,'" "Can Upzoning Increase Housing Supply and Affordability?," "How Filtering Increases Housing Affordability," "Dynamic Planning for Affordability," and "Smart Growth C’est Bon," plus this recent news article, "New Developments Lower Rents in Surrounding Neighborhoods, Study Says."

If that’s not enough, I’ve listed below several high-quality peer-reviewed publications which indicate that large-scale upzoning tends to increase affordability for both moderate- and low-income households through filtering, as some households move from existing, lower-priced housing into the new units. This does not eliminate the need for housing subsidies, but can significantly increase affordability for moderate-income households that don't quality for subsidies, and increases the number of families that can be housed with a given subsidy budget.

Brian J. Asquith, Evan Mast and Davin Reed (2019), Supply Shock Versus Demand Shock: The Local Effects of New Housing in Low-Income Areas, Working Paper 19-316 W. E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research. (Subsequently published by The Review of Economic and Statistics)

Jake Blumgart (2021), How Does New Construction Affect Nearby Housing Prices? City Monitor.

Vicki Been, Ingrid Gould Ellen, and Katherine O’Regan (2019), “Supply Skepticism: Housing Supply and Affordability,” Housing Policy Debate.

Bethel Cole-Smith and Daniel Muhammad (2020), The Impact of an Increasing Housing Supply on Housing Prices: The Case of the District of Columbia, 2000 -2018, District of Columbia Government.

Hongwei Dong (2021), “Exploring the Impacts of Zoning and Upzoning on Housing Development: A Quasi-experimental Analysis at the Parcel Level,” Journal of Planning Education and Research.

Xiaodi Li (2019), Do New Housing Units in Your Backyard Raise Your Rents?, NYU Furman Center.

Evan Mast (2019), The Effect of New Luxury Housing on Regional Housing Affordability, W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research.

Andreas Mense (2020), The Impact of New Housing Supply on the Distribution of Rents, Beiträge zur Jahrestagung des Vereins für Socialpolitik, Gender Economics, ZBW - Leibniz Information Centre for Economics.

Leah Platt Boustan, et al. (2019), Does Condominium Development Lead to Gentrification?, Working Paper 26170, National Bureau of Economic Research.

Dowell Myers and Jung Ho Park (2019), “A Constant Quartile Mismatch Indicator of Changing Rental Affordability in U.S. Metropolitan Areas,” Cityscape, Vol. 21/1, pp. 163-200.

Dowell Myers and Jungho Park (2020), Filtering of Apartment Housing between 1980 and 2018, National Multifamily Housing Association Research Foundation.

Shane Phillips, Shane Phillips and Michael Lens (2021), Research Roundup: The Effect of Market-Rate Development on Neighborhood Rents, UCLA Lewis Center for Regional Policy Studies.

Stuart S. Rosenthal (2014), “Are Private Markets and Filtering a Viable Source of Low-Income Housing? Estimates from a ‘Repeat Income’ Model,” American Economic Review, Vo. 104, No. 2, pp. 687-706. (DOI: 10.1257/aer.104.2.687).

Miriam Zuk and Karen Chapple (2016), Housing Production, Filtering and Displacement: Untangling the Relationships, Institute of Governmental Studies.

Housing Supply Skeptics

Housing supply skeptics, such as The Planning Report, Andrés Rodríguez-Pose and Michael Storper, and Patrick M. Condon, blame high housing prices on "fiscalization," greedy speculators, and capitalism. They reject the idea that upzoning can increase housing affordability and economic opportunity, arguing that it only benefits the rich, harms the poor, and leads to gentrification. To increase affordability they recommend coop housing, housing subsidies, public housing, inclusionary requirements, plus new taxes and price control regulations.

Supply skeptics seldom acknowledge the potential downsides of these policies. For example, excessive inclusivity requirements can reduce new housing production, which reduces future housing affordability, rent controls can discourage rental housing investments, and public housing can concentrate poverty and discourage families from moving to new areas that have better economic opportunities but market-priced rents.

The Quality of Their Evidence

Supply skeptics often use anecdotal evidence, such as high prices of new high-rise condominiums after a single parcel was upzoned, that do not reflect proposed polices, such as large-scale upzoning. As previously mentioned, Planning Report editor David Abel sent me various articles ("The limits to deregulation and upzoning in reducing economic and spatial inequality," "Residential Upzoning Risks Unintended Consequences," and "Build More Housing' Is No Match for Inequality") that he believes justify supply skepticism, but they are all interviews or opinion pieces that lack critical analysis or peer review. Some actually indicate that upzoning generally does increase affordability but emphasizes constraints and uncertainties, pointing out that upzoning alone cannot solve homelessness, and benefits vary depending on specific conditions, which they then claim demonstrates that upzoning is totally ineffective and harmful.

These publications often cite and misrepresent Yonah Freemark's study, "Upzoning Chicago: Impacts of a Zoning Reform on Property Values and Housing Construction," which found that property values increased, and few new units were built, after some Chicago transit station area parcels were upzoned. Supply skeptics claim that this proves that upzoning cannot increase supply or affordability, but that misrepresents the research. The study area was a tiny portion (less than 2%) of the city’s residential area. As Freemark stated about his study: "In no way is it suggesting that increases in the number of housing units won’t eventually lead to lower prices overall."

Supply skeptics ignore this conclusion. Anybody who claims that Freemark's study proves that broad upzoning is ineffective at adding supply and drives up housing prices is either ignorant or dishonest. Read the study!

A few older academic studies do suggest that increasing housing supply is ineffective at increasing affordability. Richard Applebaum and John Gilderbloom's 1983 study, "Housing Supply and Regulation: A Study of the Rental Housing Market," found that increasing rental housing construction does not necessarily reduce rents, and Andrejs Skaburskis' 2006 study "Filtering, City Change and the Supply of Low-priced Housing in Canada" concluded that the filtering process is too slow to significantly reduce low-income households housing burdens. However, those studies are old and did not account for important confounding factors. For example, rental housing growth tends to be greatest in cities that also have more population and employment growth that drives up housing costs; their rent increases would probably have been higher with less housing supply growth, as Cole-Smith and Muhammad found.

The only recent quantitative study I’ve seen that supports supply skepticism is Rodríguez-Pose and Storper's article, “Housing, urban growth and inequalities: The limits to deregulation and upzoning in reducing economic and spatial inequality" published in Urban Studies in 2019. It uses stained arguments and questionable evidence to conclude that upzoning only benefits affluent people and harms the poor. For example, it finds that regional economic growth rates are not significantly affected by the degree of housing regulation (ignoring all possible confounding factors), and so concludes that deregulation does not increase economic opportunity. That is terrible logic, and an example of quality of their analysis. That paper was subsequently criticized by professors Michael Manville, Michael Lens, and Paavo Monkkonen in "Zoning and Affordability: A Reply to Storper and Rodríguez-Pose." They point out numerous inaccuracies and technical problems with Storper and Rodríguez-Pose’s research. James Brasuell discussed these opposing claims in a column published a few months ago, "An Academic Debate with Very Real Consequences: Land Use Regulations and the Cost of Housing." I suggest that anybody who wants to understand this debate review these articles.

Comparing Research Quality

The table below compares these three ideologies.

|

|

Free Market Advocates |

Housing Experts |

Supply Skeptics |

|

Who they are |

Advocates of free markets and deregulation, and pro-sprawl industry-supported organizations. |

Planning professionals and urban economists. YIMBY activists. |

Marxist activists and some academics. |

|

Who they blame |

Urban growth boundaries and other Smart Growth policies. |

Zoning regulations that limit affordable housing types, and other policies that favor expensive over lower-cost housing. |

Large corporations, greedy speculators, the rich, and capitalism. |

|

What they recommend |

Eliminate restrictions on urban expansion, and allow more sprawl so developers can build on cheap urban fringe land. |

Reform regulations to allow more compact infill, favor moderate-price housing, improve infrastructure in walkable urban neighborhoods, and subsidize housing for families with special needs. |

Significantly increase government subsidies, public housing projects, inclusivity requirements, land value capture taxes, and rent control regulations. |

|

Quality of their evidence |

Poor. Mostly published by advocacy organizations. Little peer review. |

Good. Many high quality peer-reviewed publications. Ongoing research to address uncertainty. |

Poor. Mostly anecdotal evidence, and some highly criticized and disputed studies. |

This suggests that both Free Market Advocates and Supply Skeptics rely on poor quality evidence, and that neither ideological extreme offers comprehensive solutions to unaffordability problems; their prescriptions are only appropriate in specific, limited situations. Housing experts have solid research that can help guide planners to develop the combination of policies that can achieve affordability and opportunity goals.

There is, I believe, a positive message here. If we follow the science we can identify excellent solutions to unaffordability problems. There is abundant credible evidence that large-scale upzoning to allow more affordable housing types in walkable urban neighborhoods can significantly increase housing and transportation affordability for low- and moderate-income households. To accomplish this, it must be sufficient in scale to create a competitive market for upzoned parcels, as discussed in a previous blog.

For example, if a neighborhood needs 100 new units per year to meet population growth and a typical infill project adds four units, and on average a parcel is sold once every ten years, it needs 25 annual infill projects, which requires upzoning at least 750 parcels that so each year there are at least 75 parcels for sale that are suitable for infill. To maximize affordability, development policies should favor lower-priced housing, with lower development fees and approval requirements, and reduced parking requirements for moderate-priced houses, investments in affordable transport modes, more mixed development, plus housing subsidies for households that need them. Put this all together and we can have affordable, accessible, and inclusive high-opportunity communities.

Readers, please help identify any credible overlooked evidence. If you know of recent peer-reviewed studies that use original, quantitative analysis to demonstrate that large-scale upzoning that allows significantly more lower-priced housing types (multiplexes, townhouses and mid-rise apartments with unbundled parking) in attractive, high-population growth cities fails to increase housing affordability, please post them in the comments section below.

Planetizen Federal Action Tracker

A weekly monitor of how Trump’s orders and actions are impacting planners and planning in America.

Chicago’s Ghost Rails

Just beneath the surface of the modern city lie the remnants of its expansive early 20th-century streetcar system.

San Antonio and Austin are Fusing Into one Massive Megaregion

The region spanning the two central Texas cities is growing fast, posing challenges for local infrastructure and water supplies.

Since Zion's Shuttles Went Electric “The Smog is Gone”

Visitors to Zion National Park can enjoy the canyon via the nation’s first fully electric park shuttle system.

Trump Distributing DOT Safety Funds at 1/10 Rate of Biden

Funds for Safe Streets and other transportation safety and equity programs are being held up by administrative reviews and conflicts with the Trump administration’s priorities.

German Cities Subsidize Taxis for Women Amid Wave of Violence

Free or low-cost taxi rides can help women navigate cities more safely, but critics say the programs don't address the root causes of violence against women.

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.

planning NEXT

Appalachian Highlands Housing Partners

Mpact (founded as Rail~Volution)

City of Camden Redevelopment Agency

City of Astoria

City of Portland

City of Laramie