Patrick Condon's new book, "Sick City: Disease, Race, Inequality and Urban Land" recommends tax reforms and housing subsidies to create more affordable and inclusive communities. It is attractive propaganda that deserves critical analysis.

In a new, free book, Sick City: Disease, Race, Inequality and Urban Land, and an associated article published by The Planning Report, "Density, Affordability, & The 'Hungry Dogs' of Land Price Speculation," Professor Patrick M. Condon argues that current development policies drive up housing prices, creating inequity and public health problems. Most planners would agree.

However, Condon oversimplifies the problems and oversells his solutions. He blames housing unaffordability entirely on current tax policies, and recommends only two solutions, land value taxes and more social housing. Most planners will be intrigued but need objective and credible evidence to be persuaded. Condon fails to deliver. Instead he plays an ugly game called, "my solution is better than your solution, so your solution is useless." In particular, he argues with great certitude but inaccurate evidence that upzoning cannot increase affordability, ignoring an abundance of contrary research.

When defining the problem, Condon confuses cause and effect. Yes, urban housing prices are increasing faster than inflation or incomes, and some types of housing have been "fiscalized," meaning that large corporations invest in them for profit, but most economists recognize these as symptoms of artificial scarcity caused by restrictive development policies. Large corporations find housing investments profitable in communities that prevent developers from building the types of homes that consumers demand, driving up prices. This demonstrates, once again, the law of supply and demand

Condon presents land value taxes as a panacea for unaffordability, inequity and ill health. He bases his recommendations on 140-year-old theories by Henry George. Most economists agree with the basic concepts, with caveats. The problem with Georgist theory is a lack of empirical evidence. Weak forms have been implemented in a few jurisdictions, including Hawaii and Pittsburgh, but it has never been fully applied. Even if the theory is sound, it faces significant practical, institutional, and political obstacles.

Smart taxes and fees are lower on socially beneficial goods, such as healthy food and basic housing, and high on socially harmful goods, such as tobacco and alcohol. To improve affordability and resource efficiency, property taxes, development fee and project approval requirements can be structured to favor lower-priced infill housing. Many of these reforms can be implemented quickly. For example, a municipal government can reduce development fees and expedite project approvals for compact, moderate-priced, housing projects in walkable urban neighborhoods to reflect their lower public service costs, traffic impacts and pollution emissions compared with low-density urban fringe housing.

Condon advocates affordable housing subsidies and inclusivity requirements without discussing their risks and limits. These strategies can usually satisfy only a small portion of affordable housing demand, and by increasing development costs they often reduce total housing production and therefore overall affordability, particularly over the long run. As Emily Hamilton explains,

While inclusionary zoning provides large benefits for a small number of low- and middle-income households, most empirical evidence indicates that it drives up prices for others and reduces access to housing overall. The policy’s emphasis on providing below-market-rate housing in new construction that’s identical to market rate housing means that resources dedicated to social housing won’t go as far — or be distributed as equitably — as they could be if they were targeted to low-income individuals as housing vouchers or cash.

For example, if the cheapest housing units cost $200,000 to build, and regulations require that 10% be priced at $100,000, the nine other units each bears an additional $11,111 ($100,000/9) cost. This is small for high-priced housing (1% of a million dollar unit) but large for lower-priced housing (5% of a $200,000 unit). This can significantly reduce the number of moderate-priced homes built.

As described in Joe Cortright's recent column, Inclusionary Zoning: Portland’s Wile E. Coyote moment has arrived, Portland, Oregon's 20% inclusivity mandate caused affected housing development to decline by two-thirds. In markets with lots of latent demand for high-priced housing, a portion of these costs will be capitalized into land values.

Like any medicine, inclusivity requirements should be implemented with caution. Condon actually recommends (p. 115) that Portland and other affluent cities impose 50% inclusivity requirements. This is unrealistic, it will lead to less housing being developed, particularly moderate-priced units, and so harm moderate-income families.

While we wait for the land value tax revolution, Condon recommends building lots of social housing, as they do in Vienna. He offers planning pornography: lovely images of beautifully designed and maintained working-class housing blocks, backed with strong rent controls and affordable housing mandates. However, Condon fails to provide context: many other factors contribute to Austria's relatively affordable housing, particularly development policies that favor production of compact multi-family housing over single-family sprawl. Since compact housing has lower land, construction and operating costs, this reduces the total costs of producing both market and social housing. Even if U.S. cities significantly expand social housing production, it would take decades for a North American city to build the quantity that exists in Vienna.

Condon ignores problems that poorly planned social housing can cause. There are many examples of well-intended social housing programs that result in shoddy homes that are suboptimal in design and location, fail to meet occupants' needs, concentrate and isolate poverty, impose high transportation costs, and discourage families from moving to neighborhoods with better economic opportunities. Without the upzoning that Condon criticizes, social housing tends to be excluded from high-opportunity neighborhoods, contributing to poverty concentration. Let me offer an example I happen to be familiar with.

Iran's revolutionary government established the Maskan-e-Mehr (Kindness Housing) program to supply affordable homes for low-income families. It built high-rise housing at the urban fringe where public infrastructure and services are lacking. A study I co-authored found that due to this isolation, residents were forced to rely on motorized transport (private cars, taxis, and public transit) for virtually all errands, causing average households to spend about 70% of their income on housing and transport combined. This type of social housing is not really affordable or suitable to most households, so many moved back to older private housing in the city center.

Condon marshals two bits of evidence to claim that increasing allowable density cannot increase housing affordability. First, he states (footnote 147), "Sadly, the evidence suggests that increasing allowable density, as many public officials propose, in order to increase affordability, can have the opposite effect. One study from Chicago drew much attention for providing strong evidence of the counter-intuitive consequence of increasing apparent housing ‘supply’ to meet ‘demand’ and thus lower prices. It did not. It raised per square foot housing prices instead."

Condon cites a column by Richard Florida, "Does Upzoning Boost the Housing Supply and Lower Prices? Maybe Not," which in turn cites Yonah Freemark’s study, "Upzoning Chicago: Impacts of a Zoning Reform on Property Values and Housing Construction."

But Freemark’s study is very specific and limited. It examined changes in property values after a small portion of Chicago land (less than 2% of the total) was upzoned. Freemark stated that the study does not invalidate the basic laws of supply and demand. "In no way is it suggesting that increases in the number of housing units won’t eventually lead to lower prices overall," he wrote.

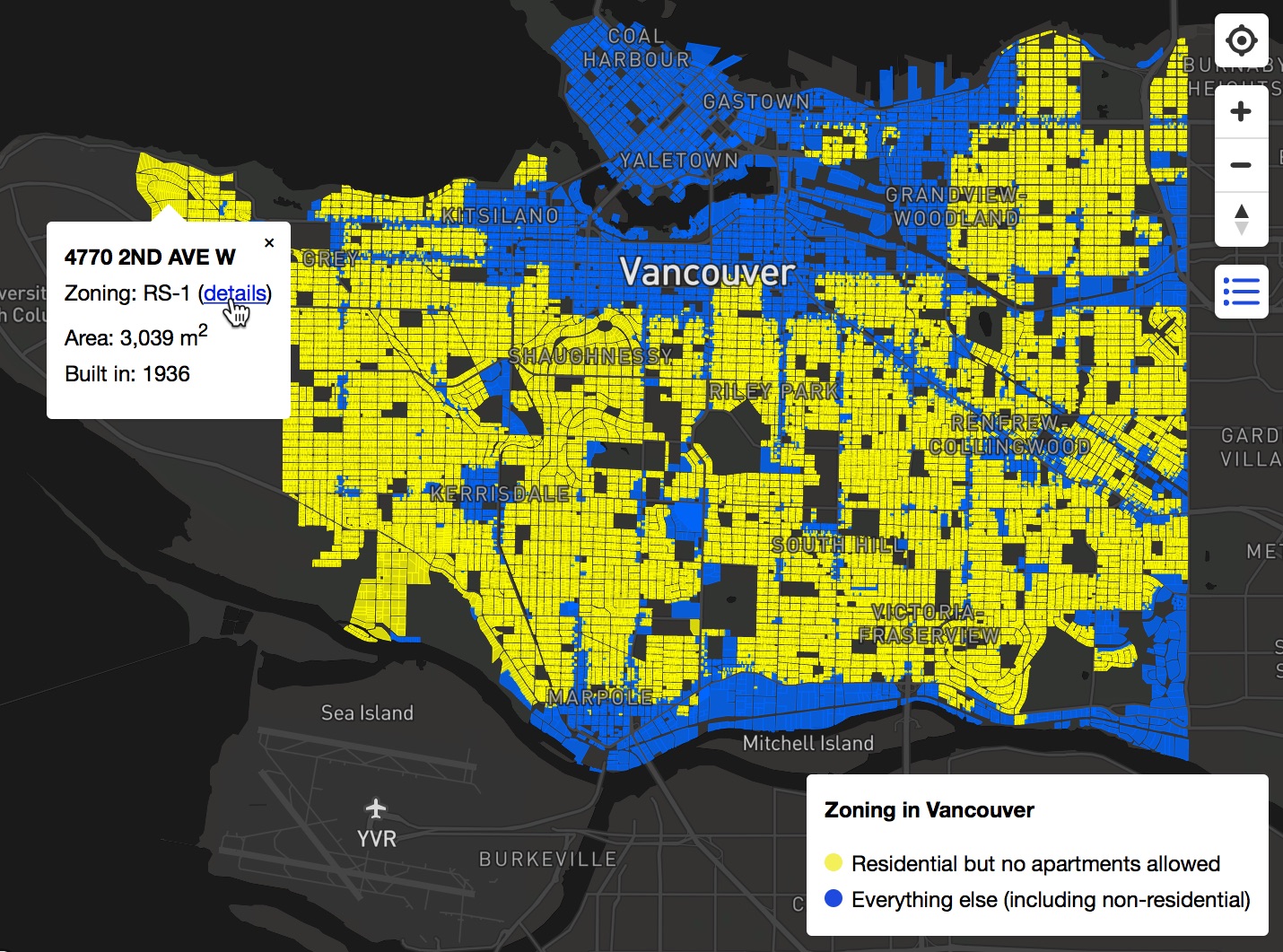

Condon similarly misrepresents evidence from Vancouver. During the last two decades, the city approved numerous high-rise downtown apartments. Such housing is attractive but costly to build and maintain, and represents a tiny portion of total regional housing. Even these can increase housing affordability through filtering, as some households move from existing units into new downtown highrises, but the numbers are too small by themselves to significantly affect regional housing prices. Despite strong growth in demand by moderate-priced housing, the city has not significantly upzoned residential neighborhoods, as illustrated in the map below. Yellow indicates the neighborhoods that only allow low-density housing (to be fair, these areas allow up to three units per parcel, but the additional units are small and relatively costly per square foot to construct).

To significantly increase affordability, Vancouver should upzone the 2/3 of its residential land that currently excludes the most affordable types of housing—townhouses and mid-rise (3-6 story) multifamily with unbundled parking. In contrast, Montreal allows mid-rise housing on 2/3 of its residential land, twice as much as in Vancouver, and its housing prices are a third lower, as discussed in my recent column, "Smart Growth C'est Bon!."

Condon writes, "unfortunately, in all the cases that I've examined throughout North America, what happens when you do a rezoning is you let the hungry dogs of land price speculation and inflation loose across the landscape with the intention of enhancing affordability."

Condon is wrong to claim that upzoning has been tried and failed. Where it is broadly applied, it has succeeded, as discussed in my previous columns, "How Filtering Increases Housing Affordability" and "Don't Miss the Middle: The Critical Role of Moderate-Priced Housing to Affordability." Also see a recent review by Shane Phillips, Michael Manville, and Michael Lens, "The Effect of Market-Rate Development on Neighborhood Rents," Xiaodi Li's, "Do New Housing Units in Your Backyard Raise Your Rents?," and Daniel Herriges's, "The Connectedness of Our Housing Ecosystem." Planners should choose this academic research over Condon's anecdotal evidence.

Not every upzoning or infill project will significantly increase affordability. Let me specify the scale of upzoning needed. A basic economic principle is that, to maximize efficiency and equity, markets should respond to consumer demands. If the number of people who want to live in a neighborhood increases by a certain amount, allowable densities should increase by that amount, and to maximize affordability and resource-efficiency, development policies should favor lower-cost, infill housing in walkable urban neighborhoods where residents can minimize their motor vehicle travel and associated costs.

To create a competitive market for upzoned land requires at least three upzoned parcels on the market for every desired additional unit, and because a typical residential parcel is put on the market about once a decade, this means that for affordability sake, a city should upzone 30 parcels for each housing unit that neighborhood needs. For example, if regional population is growing at 1.5% annually, a 1,000 home neighborhood should add 15 units annually to accommodate its share of growth. If a typical multiplex or townhouse infill project adds three net units, the neighborhood needs five of those infill projects per year. To ensure that developers can find affordable land, the market needs at least 150 parcels upzoned to allow multiplexes and townhouse. With a competitive market for upzoned land, land prices may increase modestly, but not the huge increases that occur when a single parcel is upzoned.

For example, if a single low-density parcel is upzoned to allow four townhouses, it's price might increase from $1,000,000 to $2,000,000, but if 150 parcels are upzoned, creating a competitive market, prices are likely to increase from $1,000,000 to just $1,200,000, because other upzoned parcels are for sale, limiting price appreciation.

Planners beware. Condon's book is attractive propaganda, that is, information selected to support a particular conclusion. It is well presented and likely to persuade people unfamiliar with these issues, reinforcing supply skepticism and bad policies.

I will happily agree that property tax and development policy reforms can encourage more efficient development, and that some households need social housing. However, Condon does planners, housing advocates, and their clients a disservice by rejecting one of the most effective policies for increasing affordability: upzoning in walkable urban neighborhoods.

For More Information:

Brian J. Asquith, Evan Mast and Davin Reed (2019), Supply Shock Versus Demand Shock: The Local Effects of New Housing in Low-Income Areas, Working Paper 19-316 W. E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research.

Jake Blumgart (2021), How Does New Construction Affect Nearby Housing Prices? City Monitor.

Vicki Been, Ingrid Gould Ellen and Katherine O’Regan (2019), “Supply Skepticism: Housing Supply and Affordability,” Housing Policy Debate.

Bethel Cole-Smith and Daniel Muhammad (2020), The Impact of an Increasing Housing Supply on Housing Prices: The Case of the District of Columbia, 2000 -2018, District of Columbia Government.

Joe Cortright (2017), The End of the Housing Supply Debate (Maybe), City Observatory.

Hongwei Dong (2021), “Exploring the Impacts of Zoning and Upzoning on Housing Development: A Quasi-experimental Analysis at the Parcel Level,” Journal of Planning Education and Research.

Xiaodi Li (2019), Do New Housing Units in Your Backyard Raise Your Rents?, NYU Furman Center.

Evan Mast (2019), The Effect of New Luxury Housing on Regional Housing Affordability, W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research.

Dowell Myers and Jung Ho Park (2019), “A Constant Quartile Mismatch Indicator of Changing Rental Affordability in U.S. Metropolitan Areas,” Cityscape, Vol. 21/1, pp. 163-200.

Dowell Myers and Jungho Park (2020), Filtering of Apartment Housing between 1980 and 2018, NMHC Research Foundation.

Shane Phillips, Shane Phillips and Michael Lens (2021), Research Roundup: The Effect of Market-Rate Development on Neighborhood Rents, UCLA Lewis Center for Regional Policy Studies.

Planetizen Federal Action Tracker

A weekly monitor of how Trump’s orders and actions are impacting planners and planning in America.

Maui's Vacation Rental Debate Turns Ugly

Verbal attacks, misinformation campaigns and fistfights plague a high-stakes debate to convert thousands of vacation rentals into long-term housing.

San Francisco Suspends Traffic Calming Amidst Record Deaths

Citing “a challenging fiscal landscape,” the city will cease the program on the heels of 42 traffic deaths, including 24 pedestrians.

Defunct Pittsburgh Power Plant to Become Residential Tower

A decommissioned steam heat plant will be redeveloped into almost 100 affordable housing units.

Trump Prompts Restructuring of Transportation Research Board in “Unprecedented Overreach”

The TRB has eliminated more than half of its committees including those focused on climate, equity, and cities.

Amtrak Rolls Out New Orleans to Alabama “Mardi Gras” Train

The new service will operate morning and evening departures between Mobile and New Orleans.

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.

Heyer Gruel & Associates PA

JM Goldson LLC

Custer County Colorado

City of Camden Redevelopment Agency

City of Astoria

Transportation Research & Education Center (TREC) at Portland State University

Jefferson Parish Government

Camden Redevelopment Agency

City of Claremont