To increase affordability communities should support moderate-priced housing development. This increases housing options for middle-income households, and for lower-income through filtering, as households move from low- to moderate-priced units.

There are passionate debates concerning the problems and solutions of housing unaffordability. Many people want to blame greedy developers, speculators, wealthy foreigners, short-term rentals, the tech industry, or the “rich" for rising urban housing prices. These certainly do increase housing prices and displacement, but only if moderate-priced infill development is constrained. It is therefore equally accurate to blame rising housing prices on public policies that discourage moderate-priced infill development, such as restrictions on compact and affordable housing types, inclusivity requirements, minimum parking requirements, development impact fees, complex project approval requirements, and heritage preservation rules. These policies favor expensive housing over cheaper infill housing, preventing the market from delivering moderate-priced housing that serves middle-income households now and becomes the affordable housing stock of the future.

An efficient and equitable land market responds to changing demands: if the number of people who want to live in an area increases by, say, 30%, allowable densities should increase by that amount. Locking in lower densities excludes some potential residents, particularly moderate-income households that don't quality for subsidized housing but are outbid by wealthier households for scarce market housing. By reforming these policies, we can have it all: neighborhoods with more low-, medium-, and high-income households living together. This is important, because mixed-income infill provides many economic, social and environmental benefits.

This is a timely issue. For example, our city, Victoria, British Columbia, is considering whether to approve the Cook Street Plaza, a mixed-use development that will provide 113 housing units, priced 10% below market rates due to provincial tax incentives. A city councilor, who claims to be an affordable housing advocate, recently told me that even at the reduced price he considers these units expensive and therefore not worth his support.

This is, I believe, the wrong way to evaluate affordability impacts. We should recognize indirect and long-term effects, and the important role that moderate-priced housing plays in overall affordability.

What do I mean by "moderate priced"? It is housing that is affordable to middle-income households, and therefore the types of houses that families often move up to from lower-priced units. For example, if $500-1,500 per month rent or mortgage is considered affordable, then $1,500-3,000 per month housing is moderate.

Moderate-priced housing increases affordability in three ways:

- By providing more affordable housing for moderate-income households, many of whom pay more than is considered affordable, or are forced to choose cheaper urban-fringe housing that has high transportation costs.

- Through filtering, as some households move from their existing lower-priced housing in the new units, which frees up the lower-priced units they occupy.

- As the new housing depreciates in value, adding to future lower-price housing supply. Increasing moderate-priced housing supply tends to accelerate depreciation rates. Where moderate-priced housing development lags population growth, older homes will only depreciate about 1% annually, so after a decade, a $500,000 unit will sell for $450,000. But if the rate of development meets or exceeds population growth housing can depreciate at 3% annual, so the same house will sell for a much more affordable $350,000.

As a result, a new development's affordability impacts should be evaluated based not only on its initial prices but also on its effects on the prices of other homes, what Daniel Herriges describes as an ecological model of housing markets. Most lower- and moderate-income households occupy older homes. Older home prices are affected by overall housing supply; building new moderate-priced housing drives down prices now, by freeing up lower-priced units, and even more over the long-run as the new units depreciate and add to the stock of older, lower-priced housing. The current shortage of lower-priced housing results, in part, from development policies that discouraged construction of compact, moderate-priced housing, such as basic townhouses and apartments, during the last few decades.

There is good research on these effects, as discussed in Daniel Herriges', "The Connectedness of Our Housing Ecosystem," Stuart Rosenthal's study, "Are Private Markets and Filtering a Viable Source of Low-Income Housing? Estimates from a 'Repeat Income' Model," published in the American Economic Review, Miriam Zuk and Karen Chapple’s study, "Housing Production, Filtering and Displacement: Untangling the Relationships," and my Planetizen column, How Filtering Increases Housing Affordability.

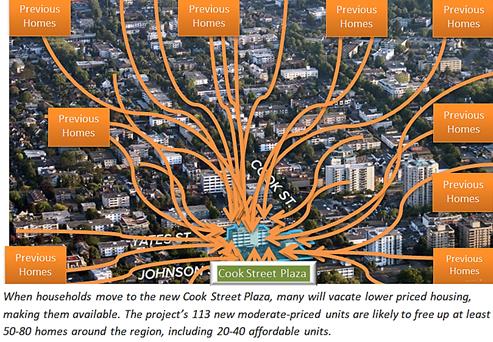

A recent study by economist Evan Mast found that building market-price apartments causes a kind of housing musical chairs, as households move into new units. They study indicates that every 100 new market-rate units frees up, on average, 45-70 below-median (moderately affordable) and 17-39 bottom-quintile (very affordable) housing units. Since his study included higher-priced apartments, the affordability benefits are probably higher for moderate-priced units. This suggests that the Cook Street Plaza's 113 moderate-priced units will free up at least 50-80 existing homes for new households, including 20-40 affordable units, in addition to the direct benefits to the households that move into the building.

In this way, the Cook Street Plaza project is equivalent to building 20-40 affordable housing units. Unfortunately, this effect is virtually invisible; there is no media event when lower-income households are able to move into the vacated older units. Although the research is solid, it requires an act of faith to believe that increasing moderate-priced housing supply will benefit low- as well as moderate-income families.

Because of its location, the Cook Street Plaza condominiums are actually more affordable and beneficial than conventional analysis recognizes, as discussed in my previous column, "Selling Smart Growth." Because it is in a walkable urban neighborhood residents can reduce their transportation expenses. Reducing one car (going from two to one, or one to zero) typically saves a about $5,000 annually. If these savings are used to purchase a more valuable home, a typical household will gain about $65,000 in additional equity compared with a cheaper suburban house with higher vehicle expenses.

Recent research shows that residents of more walkable communities have lower housing foreclosure rates, indicating better economic resilience, because they avoid the large financial risks associated with automobile dependency, for example, when a car breaks down or crashes. Living in a more central location also improves health and traffic safety, and reduces the traffic congestion, road and parking infrastructure costs, accident risk, and pollution emissions that household imposes on other road users.

Many policies involve trade-offs between low- and moderate-priced housing development. For example, inclusivity regulations, which require developers to subsidize a portion of housing units, might provide a small number of low-priced units but generally reduce development of a larger number of moderate-priced units, since those are the least profitable and therefore the first to be eliminated, as discussed in my column, "What the Market Can Bear: Defining Limits to Inclusive Housing Requirement." In a typical example, increasing inclusivity requirements from 10% to 30% adds 115 low-priced units, but reduces total housing production by 300 units. Mast's research indicates that this will prevent 108-210 moderate-priced units from becoming available through filtering, as households move into the new units, including 40-117 low-priced units.

There are similar trade-offs between preserving old lower-priced housing or allowing their replacement by larger, moderate-priced developments. For example, in our community, the 34-unit Beacon Arms Apartment is being replaced with a new 87-unit building. The 53 additional units should free up between 23-37 units through filtering. This suggests that overall affordability, efficiency, safety, and disability access can increase if old rental homes and apartment buildings are replaced by larger, moderate-priced buildings that incorporate modern construction standards. Anti-demolition policies that preserve older building stock may harm disadvantaged residents overall.

To encourage moderate-price infill development communities need policies that encourage compact housing types, often called the Missing Middle, such as townhouses and low-rise apartments, since they tend to have the lowest land, construction, and future operating costs. Compared with a single-family house, a townhouse is generally 30% cheaper, and a low-rise apartment 50% cheaper, to build and heat than a comparable size and quality single-family house, with even greater savings if parking is unbundled, so residents are not forced to pay for costly parking spaces they don’t need.

The following policies can support moderate-priced infill housing development:

- Increase allowable densities in residential neighborhoods. This reduces infill development costs, increasing moderate-priced project feasibility.

- Allow an additional story for corner lots, larger lots (at least 1,000 square meters), and on busier streets (arterials or sub-arterials). These locations minimize negative impacts on neighbours.

- Exempt or significantly reduce inclusivity mandates, development impact fees, parking minimums and project approval requirements for moderate-priced housing. Many communities provide such exemptions and reductions to special "social housing" projects, but not moderate-priced housing. This is important because such costs are particularly burdensome to smaller and moderate-priced developments.

- Reduce or eliminate parking requirements and require or encourage unbundling (parking rented separately from housing units), so residents are not forced to pay for parking spaces they do not need.

- Mandate or reward energy-efficient housing, and support efficiency retrofits of existing homes. Building energy is a major financial cost and source of emissions, so improving efficiency helps achieve affordability and environmental goals.

- Improve affordable housing design. Municipal governments can support contests, planning charrettes, and workshops to encourage better design. The Affordable Housing Design Advisor, the Missing Middle Website, and Portland's Infill Design Project provide resources for improving lower-priced housing design.

Politically, these policies can be considered to represent the radical center. In most North American communities, NIMBY (not in my backyard) is dominant. Using rhetoric borrowed from socialism ("increasing density just benefits rich developers"), environmentalism ("we must protect our trees"), and tribalism ("apartments attract undesirables"), this attitude prevents moderate-priced infill in most residential neighborhoods, relegating such housing to old industrial sites and busy roadways. However, these arguments are generally wrong (moderate-priced infill benefits low- and middle-income households, reduces habitat displacement, and may eventually be occupied by current neighborhood residents when they want to downsize from their single-family homes), and being challenged by a new generation of YIMBY (yes in my backyard) activists. Activists in my community now use the term GHIMBY (good housing in my backyard), recognizing that good design (interesting building details, privacy protection, suitable landscaping, policies to minimize vehicle traffic and parking conflicts, etc.) can overcome many objections to infill.

No single policy can solve all housing problems, but it is important to understand housing market dynamics in order to identify truly effective solutions. Those often involve supporting moderate-priced housing that does not require subsidies but should not be burdened by unnecessary regulations, fees or approval requirements.

What do we want? More moderate-priced infill housing! When do we need it? Now!

Maui's Vacation Rental Debate Turns Ugly

Verbal attacks, misinformation campaigns and fistfights plague a high-stakes debate to convert thousands of vacation rentals into long-term housing.

Planetizen Federal Action Tracker

A weekly monitor of how Trump’s orders and actions are impacting planners and planning in America.

In Urban Planning, AI Prompting Could be the New Design Thinking

Creativity has long been key to great urban design. What if we see AI as our new creative partner?

Milwaukee Launches Vision Zero Plan

Seven years after the city signed its Complete Streets Policy, the city is doubling down on its efforts to eliminate traffic deaths.

Portland Raises Parking Fees to Pay for Street Maintenance

The city is struggling to bridge a massive budget gap at the Bureau of Transportation, which largely depleted its reserves during the Civd-19 pandemic.

Spokane Mayor Introduces Housing Reforms Package

Mayor Lisa Brown’s proposals include deferring or waiving some development fees to encourage more affordable housing development.

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.

Gallatin County Department of Planning & Community Development

Heyer Gruel & Associates PA

JM Goldson LLC

City of Camden Redevelopment Agency

City of Astoria

Transportation Research & Education Center (TREC) at Portland State University

Jefferson Parish Government

Camden Redevelopment Agency

City of Claremont