If certain elements of masterplanning are not carefully chosen—and their impacts not carefully explained to final decision makers—then there runs great risk that the cities we design from scratch perform worse than the cities we already have.

The term "eco city" is used to describe a very broad range of projects. Unfortunately, not all so-called "eco cities" are as sustainable as they aim or claim to be. As they mature, some of the world's most heralded eco cities may suffer from a few sustainability alligators in their sewers. While these outcomes are surely unintentional, they are nonetheless detrimental to progress of the ancient art of city building and, arguably, to the future of our civilization.

Every day, I benefit from an ambitious urban planning project of the mid-20th Century, Finland's Tapiola "Garden City". You could say this is one of the original "eco cities"; a conscious effort to step away from urbanity as it was to start all over and do it right from the start. The city center of Tapiola's shopping and community functions is neatly surrounded by lush parks, interconnected paths, bay shorelines of the Baltic Sea, and a mix of landmark high-rises, four-level apartment buildings, row houses, and single family homes. It is still considered a textbook example of good design, but perhaps the idyllic pace of a garden city succumbed to modern urban transport expectations, and trips previously acceptable by transit, bicycle, or foot became more and more attractive by car.

In Tapiola, residential and other land uses were intentionally not well mixed; in a modern society where the work commute and daily chores are not exclusively split between family members, the result is a tendency to find chained trips by car the most convenient. Experience teaches us in these situations to adamantly beef up core density, carefully mix up land uses, and more conveniently overlap public transport options. The ongoing major facelift—including a metro station beneath a significantly densified urban center of mixed uses—demonstrates that the planners caring for this pleasant community on the outskirts of Helsinki have embraced the changing circumstances of our society and reacted, hopefully, with the appropriate updates (and are not too proud to adopt such improvements).

As planners, we all have an inherent responsibility to society always to innovate and always to strive for the highest possible result in each endeavor. While we must be vigilant in all projects, these responsibilities are perhaps never more vivid than when we are masterplanning brand new cities, where tens or hundreds of thousands of people are expected to live and work. If we fail to put all our mind and heart into these projects, if we let slip the sheets of critical planning principles and lessons learned, we risk realizing unsatisfactory results, and then they are not ecocities we are building; rather, they are duplicities.

The "Ease" of Starting Over

According to "Eco-Cities – A Global Survey" prepared by the University of Westminister in 2011, there were at least 75 "urban retrofit", 72 "urban expansion", and 27 "new development" projects throughout the post-great recession world categorized as eco cities (Tapiola, by the way, is not included as one of them). I know of several others that have started since that time. Some of these involve the dramatic overhaul of very old places based on less-than-preferable experiences. Many others are completely new and intend ambitiously to springboard off best practices from around the world.

From my perspective, the technical difficulties of masterplanning projects decrease as they shift from urban retrofit, to urban expansion, and then finally to new development. The constraints of working in an existing city are multi-faceted, from physical space limitations to political processes that (usually, hopefully) include accounting for the voices of existing residents, which have a strong tendency to slow down or halt many well-intentioned changes. On greenfield city projects, working with a so-called tabula rasa makes things technically easier, but interestingly, an absence of the physical constraints (and the watchful eyes of residents) of a built city increases the risk that planners effectively let down their guard and ultimately concede to diluted plans of otherwise laudable—and achievable—design principles.

We planners might also get the idea that things are so much easier on new development projects because, when we start all over, we have the opportunity to design cities "properly" from scratch. I submit that while the design itself may be easier, realizing the design as conceived is much more difficult. It's true that in masterplanning of new cities we can shift building lines with ease and are relatively carefree what comes to ubiquitous utility vaults and NIMBYs. Still, despite all the flaws of many existing cities, it is very, very difficult for a new eco city to effectively one-up the iterative, organic evolution of many urban fabrics.

This is not an argument about carbon footprint; it is a given that a new city faces significantly higher initial environmental costs than an urban retrofit, the losses of which may be impossible to make good on. Instead, my argument is about how the ostensible freedom of designing a new city creates hidden challenges to achieving results that are better than so many existing cities.

Existing cities are not so much the result of expert planners molding and re-molding a city plan as they are the product of millions of individuals' toils, imaginations, and voices over tens, hundreds, or thousands of years. To achieve similar qualities in a brand new city, one must be sure to simultaneously carry across all the best attributes of the past and prevent these plans from getting diluted by the choices of what is almost always many orders of magnitude fewer participants in the decision making process. It is not so easy to extract all those ideas and repack them neatly into a new box, and therefore, it is a very challenging—some may say a daunting—responsibility.

Surely, many cities have their own problems, some embedded so tightly into the fabric of the place, that doing things all over again may seem obvious and, well, simpler. The truth is, however, that while designing new cities from scratch does have advantages over retrofits or expansion of existing cities, it also comes with its fair share of snares. If certain elements of masterplanning are not carefully chosen—and their impacts not carefully explained to final decision makers—then there runs great risk that the cities we design from scratch perform worse than the cities we already have. And since these cities don't yet exist, all the risk lies in the laps of its planners. Perhaps that is why it is called masterplanning?

A Case for New Cities

Now, don't get me wrong. I'm the first to advocate for the design and construction of new eco-friendly cities. After all, masterplanning new cities is part of my job. More importantly, the world is undergoing unprecedented movement towards and growth in urban areas, and the existing building stock of the world's cities simply will not support the millions of people converging upon them each year.

Retrofitment of cities and expansion within urban areas are extremely important (and yes, vastly more sustainable) activities that dramatically improve conditions, but building brand new cities is unquestionably an important and necessary part of the global urbanization trend simply because we need additional building stock. Moreover, like Tapiola fifty years ago, we need opportunities to attempt something new, to discover better systems; else, we run the risk of stifling innovation in our profession.

Moreover, just like any other group of things in our universe, it is unwieldy to attempt to balance all of human civilization in just a handful of vast megalopolises. Man, as in nature, succeeds best when bets are hedged across a diverse range of unique but interconnected elements. I think this makes sense for cities as well as species and galaxies. Local aberrations can be managed—or abandoned—without spoiling the whole. Also, when the aliens invade, it's much more difficult to exterminate us if we're not all massed together in one lump.

The Green Cities and their Mistresses

When asked what makes a place so green, people often associate the highest ranked sustainable cities with a more traditional marriage to parks. I, on the other hand, have inside knowledge about all these cities' scurrilous, secret mistresses. During interviews, we often share with clients a chart of the Siemens Green City Index that ranks over one hundred cities around the world, including many top ranked Nordic cities (full disclosure: these are where the main offices of Ramboll, the company for which I work, are located) where progress in people-friendly urban planning has been highly lauded for decades by planners and residents alike, dubbing these cities as high-profile, sustainability superstars. In addition to these trendy green pop celebrities, some of the world's elite business city big guns surprisingly also appear on the same list. While all these cities may indeed outwardly pose in storybook relationships with their doting families of parks, they all quietly hush away their sordid relationships with the downtown dominatrix: parking.

For example, it has happened more than once that someone who sees the Siemens Green City Index chart asks how places like New York City and San Francisco can be ranked so high. While there are certainly many other reasons, I unabashedly like to stir up the scandal by revealing the complicity of "parking". It's true, and to all those sensationalist daily rags out there who love nearly nothing more than a good parking scandal, I have the glossy image to prove it; unfortunately, the image is a bar chart. Many people immediately associate America with the tired, car crazy stereotype we all love to hate. It is therefore always a surprise when I explain that several of the United States' most vibrant, walkable cities also feature surprisingly low car dependence, and in most cases the cause is a prerequisite of excellent public transport combined with extremely limited (or expensive, or both) parking.

What is most interesting to me, however, is the overlay of (any) green city indices to an equally fascinating publication, the Colliers International Global CBD Parking Rate Survey, in which the world's 50 most expensive city parking rates are listed. When we do this, we see a very interesting correlation; namely, that the world's most sustainable cities are also almost always the most expensive cities in which to park. Funny, that!

Passive Scarcity versus Active Pricing Strategies

We all know that scarcity drives prices higher. In many existing cities with high sustainability scores, the concurrence of sustainability and limited parking is not always due to a conscious effort to make the city more green, but simply a default dearth of space to provide it. The effect of such scarcity, when parking is in the hands of private operators, is usually very high parking rates, and scarcity of parking combined with high prices results in excellent controls over parking demand. Subsequently, vehicle ownership and car dependence drop. This is exactly why urban household vehicle ownership rates in car-crazy America (where this rate is typically 90% across the country) can be 70% and 26% in the green cities of San Francisco and New York, respectively.

Alas, most cities do not leave parking up to the free market. Despite some limited examples of market-driven parking policy, most cities control (and, typically, spoil) their own parking destiny, since the outspoken voices of the driving minority have for decades repeatedly forced the responsibility for providing parking into the laps of all taxpayers. Fortunately, there are several excellent examples of local governments who have found the political gumption to turn this circumstance of ownership to an advantage. In fact, the world's most prestigious and esteemed sustainable cities have cleverly employed parking policy as perhaps the single most powerful tool to dial back traffic congestion, auto dependence, and subsequently transform themselves into what we know today to be the best examples of sustainable urbanity.

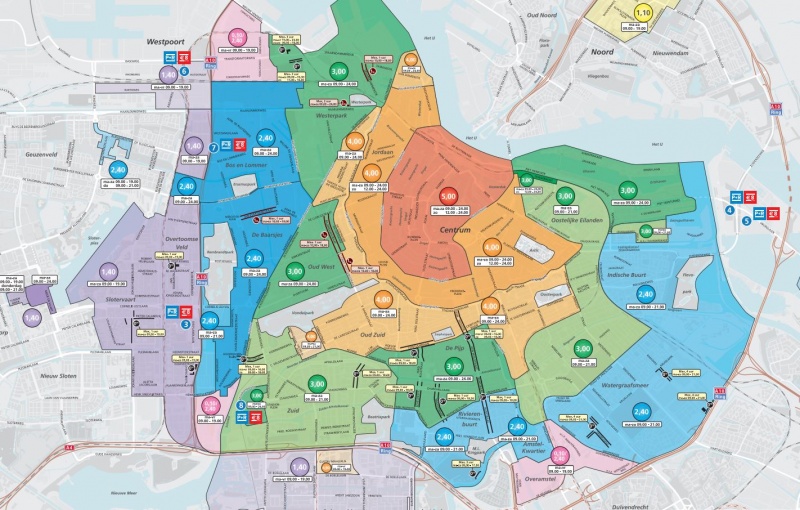

For example, both Copenhagen and Amsterdam practiced careful parking pricing strategies for several decades, all the while becoming our beloved models of modal splits. Copenhagen is well known for its annual programmed attrition of downtown parking spaces at a rate of 2-3% per year. It is notoriously expensive to own and park a car in that city. Amsterdam, with a population of 780 000, has shrunk parking supply to only 280 000 parking spaces, a ratio of .36 parking spaces per capita. Its progressive policy, also mirrored in many other European cities, including in Helsinki where I live, has resulted in a pricing strategy that markedly increases as one drives closer to the city center. Munich, a city also sparring for sustainability supremacy, has been aggressively using parking to control vehicle traffic downtown, and boasts a ratio of only .24 parking spaces per capita.

In terms of parking supply per capita, these glowing examples where strong government controls are used to achieve desired results are perhaps surprisingly only bested by the market-driven, pinstripes approach practiced in places like New York City, where privately operated parking garages controlling their own prices are arguably responsible for driving the parking-spaces-per-capita-ratio to an incredible .10.

And what about America's most walkable, transit-friendly city? My beloved Hoboken, where vehicle ownership per household is just over 60%; boasts a highly competitive parking supply per capita ratio of .40. In all these examples, the price for parking is high, particularly so the closer one gets to the city center.

While not a conclusive (or thoroughly studied) KPI on its own, by simply comparing parking capacities for various cities to population, one can still glean something about the sustainability of a place. It is in the densest cities—and especially ones where public transport is simultaneously of extremely high quality and appropriately sized—that limited parking acts as a natural deterrent to auto-dependency and therefore contributes to walkable, eco-friendly communities that top the green indices. The relevance of this value as an eco city KPI is supported, for example, by its use in the German Sustainable Building Council's evaluation methodology. When new eco cities are compared to existing cities in terms of parking supply and population, the results may be surprising.

Calling Out the Outliers

To be fair, the argument for a low parking-supply-per-capita-ratio equating to sustainable communities is neither an absolute, nor an independent truth. For example, Beijing's count of parking spaces per capita is a whopping low .07, but anyone who knows Beijing can tell you that congestion is presently a huge challenge for that city, so clearly other variables are clearly at play. That city has recently announced plans to raise downtown parking rates in an effort to control traffic (and interestingly, they are properly pricing on-street parking higher than garage parking!), but in a country where luxury cars dominate a rapidly growing industry, the new rates may still be too low, so the results of that effort remain a bit, well, smoggy.

When it comes to new cities in China, the parking and population ratios are unfortunately on the other end of the spectrum. The relatively unchecked culture for car ownership is so strong that many well-intentioned new cities are looking like breeding grounds for future congestion blight. Clearly, we must work harder to communicate the ramifications of these plans.

Of all the so-called "eco cities" out there, perhaps the two that stand out most vividly to the eyes of a transportation planner are Brazil's "Transit Oriented Development" model city of Curitiba (an urban retrofit) and United Arab Emirates' "car free" Masdar City (a new development). These cities are together unique in that they show how much can be accomplished in reducing car dependence in both existing and new urban environments by substituting intense public transport strategies.

They are also unique because of how they came to be what they are today. The former is an example of (blind?) faith in a spirited concept and the incredible political will to make it happen. The latter is a result of bold, innovative ambition and the capital resources to put a broadly untested, futuristic plan into action. Both cities are unquestionably innovators and leaders in the trend of eco cities, and we still have a lot to learn from them. We already know that Curitiba has proven itself to be a fantastic world model for focused density around central public transport corridors with little technological support. We wait anxiously to see how the high tech concepts supporting the urban plan in Masdar City come to fruition.

One interesting detail about these two cities, however, is that their relationships between car ownership and parking supply differ so greatly. While Masdar City and Curitiba both feature surprisingly high vehicle ownership rates of more than one per household—much higher than most of the world's leading sustainable cities—their provision of parking diverges considerably. Masdar City, with an anticipated population of approximately 40,000 people, will provide 1.05 parking spaces per capita when all is said and done, while Curitiba's Centro district, for example, has only 0.17 parking spaces per capita (Curitiba's Agua Verde district dials in at an incredibly low .06!)

What do these numbers tell us? Most existing sustainably-ranked cities tout vehicle ownership numbers between 0.5 and 0.7, so both cities support significantly higher vehicle ownership rates than other leading sustainable cities like Copenhagen, Munich, and New York City. The natural presumption is that this would lead to very high auto use. But in terms of parking supply, both Curitiba and Masdar flip that mobility mantra on its head by managing auto use via an unprecedented scarcity of parking. This seems to support the libertarian argument that people will smartly choose the most practical modal option—and not necessarily their car—if given the choice. The controls placed on parking (or rather, the absence of public subsidy on parking) only go to make that choice more fair.

Admittedly, I do not know enough about Curitiba to say if the apparent parking scarcity in that city is due to prescribed pricing mechanisms or other causes. I also do not know where all these cars are actually parked. My guess is that the samelaissez fairezoning code that permits unlimited density along BRT corridors may also the choice of providing parking spaces up to individual developers, who shrewdly choose to omit expensive and unprofitable parking, but that is just a hunch. Whatever the reasons, clearly modal splits in that city demonstrate that even if many people own cars, they are choosing not to use them for most of their trips.

In the case of Masdar, scarcity of parking is effectively infinite by design, as nine park & ride facilities housing 42 000 parking spaces are planned to be located around the edges of the city, and no cars are permitted inside. The mobility choice therefore occurs in tandem with that of taking up residence, and hopefully we will observe a new kind of city with sufficient mobility freedoms overcome the premise that new cities must have immediately adjacent parking facilities to be successful.

Parking Eco Cities

The relevance of this discussion to eco cities is that there is perhaps an important design guideline to derive from the relationship between parking provisions and prescribed populations. If planners of new eco-cities do not make every attempt to control parking supply in terms of both count and cost, especially in the densest, deepest parts of these cities where public transport hopefully proliferates, then they run the risk of creating urban environments that incentivize driving, and therefore undesirably shift trip choices away from the otherwise attractive public transport systems provided, resulting in a deterioration of quality of life and, implicitly, more congestion. Furthermore, I submit that the disparity between parking supply and vehicle ownership, as recognized in extremely sustainable cities such as Curitiba (and Helsinki, Amsterdam, Munich, Hoboken, San Francisco, and New York City), can be a useful indicator of how eco-friendly a new development project will really be. Scarcity, after all, should lead to more equitable pricing, which is a critical factor in modal choice.

The biggest challenge, of course, is not that urban planners don't know to manage parking. Rather, it is that when many projects meet critical decision points—political, technical, or otherwise—the urban planner is not necessarily the strongest voice, or even in, the room. When this happens, the end product does not always meet original aspirations. Therefore, we must make every effort to inform decision makers—who may be focused on other equally important priorities such as total cost and attractiveness to potential investors—of the ramifications to eco-city plans when eliminating such critically important principles.

In most cases, it comes down to building strong, trusting relationships with clients who will take your advice seriously and—dare I say it—simply telling them the truth. One cannot simultaneously have an eco-city that prioritizes walkable communities but also parks every household with two reserved spaces a few steps from homes right down to the central core districts. Rather, I submit parking should be provided in a shared, tiered structure that controls both supply and price in such a way that more abundant and cheaper parking is found around the periphery of the city, and the scarcest and most expensive parking is strategically provided at the center. This is a detailed, balanced system of both design and policy that must be carefully drawn and written into masterplans, and carried on through implementation and operation.

One end of this spectrum is Masdar City, where the price to park inside the city boundary is, effectively, infinite. But, successful examples in existing cities, such as Amsterdam highlighted above, prove that with more modest applications of this concept, any desired level of car access into the city center can be provided, from car-free, to car-balanced, to car-clogged. It's a conscious choice to cook up an eco city how one sees fit. And while there are plenty of other ingredients that go into a new eco-city stew, planners can act the master chef and enjoy a freedom to custom fit parking strategies that dictate exactly how much access cars have to a city, if only they have the confidence and the will to hold the line on fundamental design principles for making true eco cities, not duplicities.

Maui's Vacation Rental Debate Turns Ugly

Verbal attacks, misinformation campaigns and fistfights plague a high-stakes debate to convert thousands of vacation rentals into long-term housing.

Planetizen Federal Action Tracker

A weekly monitor of how Trump’s orders and actions are impacting planners and planning in America.

San Francisco Suspends Traffic Calming Amidst Record Deaths

Citing “a challenging fiscal landscape,” the city will cease the program on the heels of 42 traffic deaths, including 24 pedestrians.

Defunct Pittsburgh Power Plant to Become Residential Tower

A decommissioned steam heat plant will be redeveloped into almost 100 affordable housing units.

Trump Prompts Restructuring of Transportation Research Board in “Unprecedented Overreach”

The TRB has eliminated more than half of its committees including those focused on climate, equity, and cities.

Amtrak Rolls Out New Orleans to Alabama “Mardi Gras” Train

The new service will operate morning and evening departures between Mobile and New Orleans.

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.

Heyer Gruel & Associates PA

JM Goldson LLC

Custer County Colorado

City of Camden Redevelopment Agency

City of Astoria

Transportation Research & Education Center (TREC) at Portland State University

Jefferson Parish Government

Camden Redevelopment Agency

City of Claremont