Scandinavian countries are often praised for the forward-looking planning practices associated with social democracy. Urban planning there includes lots of enviable features, but a tour of a high-profile project outside Oslo, Norway was a reminder that even an urbanist’s paradise includes political fights, squabbles among interests, and embarrassing delays familiar anywhere else. Progressive politics encourage progressive plans, but the process and pitfalls remain the same.

Scandinavian countries are often praised for the forward-looking planning practices associated with social democracy. Urban planning there includes lots of enviable features, but a tour of a high-profile project outside Oslo, Norway was a reminder that even an urbanist's paradise includes political fights, squabbles among interests, and embarrassing delays familiar anywhere else. Progressive politics encourage progressive plans, but the process and pitfalls remain the same.

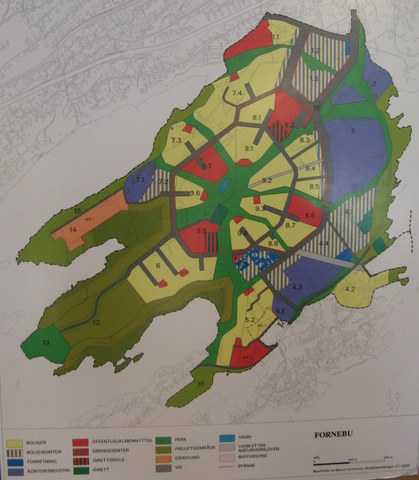

I recently toured Fornebu, a development project near Norway's capital that will turn a recently closed airport into a mixed-use project of housing and high-tech businesses (the focus of much Norwegian economic development these days). The project, on a rounded peninsula about a mile long, will have 6,000 housing units and workplaces for about 20,000 employees. (See map.) In size and components, it's not unlike New York's Battery Park City, which I've studied in depth.

The plan's green features immediately stand out. The appendages of the spider-shaped park in the middle stretch through the project to provide bike path connections among all the buildings and the green space at the center. Day care centers are sited in the brand new parks. There's also a beach, but no parking lot since most people are expected to bike, walk, or come by train.

Why were the parks built first? "We build the parks first to attract people-before the buildings," explained Hans Lingsrom, the project's executive director. (That's also a guarantee that they get built, not just promised.)

The new elementary school is very attractive, with a skylight the length of an interior mural providing good natural light. New schools in the US can be very attractive as well, but Lingsrom then described a problem I only wish we had in the US: building the school was expensive, he said, because it had so many amenities. Why was it so well equipped? "Well, you know," he said, "each school this community builds is better than the last." Residents' attempts to outdo each other prove that the old bumper stickers were right: there actually can be an arms race in education funding.

The schools have to be built first, since in Norway developers can't get permission to build unless there's adequate school capacity. That leverage was part of what allowed the public development agency to extract a commitment from developers of more than $350 per square foot (3,000 euros per square meter) for the municipality to provide schools and other services. (The apartments were valued at several times more than that.)

But this is reality, not Shangri-la, so development hiccups happen here, too: the schools had to be built first, but stand embarrassingly alone since apartment construction has slowed in the global real estate crash. Construction of the train line is currently in limbo because of the predictable fights that happen when a site is controlled by three different governments and under the purview of multiple transit agencies. Most significantly, like New York's Battery Park City, most of the housing will be high-end: 850-1,200 affordable units are planned, but the final number could include even fewer affordable homes. Norway seems to be dabbling with the US conviction that luxury developments are the appropriate focus of public development projects.

In my research in Lower Manhattan, I've been bothered by the myriad state subsidies for high-end development. It rankles that money is being spent on luxuries in a city like New York where so many people are desperately poor and the city needs hundreds of thousands more affordable housing units. Such luxury subsidies are not quite as infuriating in a country without such sizeable, extreme poverty and insecurity. In Norway, as elsewhere, a narrower gap between rich and poor puts them far ahead of the US in terms of life expectancy, mental health, and social mobility, among other measures. (Inequality correlates sharply to these social ills, as graphed here.)

The hurdles Norwegian planners had to clear would sound familiar to anyone anywhere who has had to deal with pushy developers, uncooperative bureaucracies, embarrassing delays, and agreements that turn out to not be as iron clad as they looked. But what planners at Fornebu are fighting for-great schools, a network of parks, some affordable housing, a high-tech business center, good mass transit connections, and a well-balanced community-are enough to make me want to crumple up plenty of US developers' plans and throw them in the trash. Of course, in Fornebu that trash would be sucked away by a network of vacuum tubes into an automated solid waste disposal plant. We don't need to get rid of our garbage trucks, but if we have to have planning battles, it would be nice to be fighting for such great features.

Planetizen Federal Action Tracker

A weekly monitor of how Trump’s orders and actions are impacting planners and planning in America.

Map: Where Senate Republicans Want to Sell Your Public Lands

For public land advocates, the Senate Republicans’ proposal to sell millions of acres of public land in the West is “the biggest fight of their careers.”

Restaurant Patios Were a Pandemic Win — Why Were They so Hard to Keep?

Social distancing requirements and changes in travel patterns prompted cities to pilot new uses for street and sidewalk space. Then it got complicated.

San Francisco Suspends Traffic Calming Amidst Record Deaths

Citing “a challenging fiscal landscape,” the city will cease the program on the heels of 42 traffic deaths, including 24 pedestrians.

California Homeless Arrests, Citations Spike After Ruling

An investigation reveals that anti-homeless actions increased up to 500% after Grants Pass v. Johnson — even in cities claiming no policy change.

Albuquerque Route 66 Motels Become Affordable Housing

A $4 million city fund is incentivizing developers to breathe new life into derelict midcentury motels.

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.

Heyer Gruel & Associates PA

JM Goldson LLC

Custer County Colorado

City of Camden Redevelopment Agency

City of Astoria

Transportation Research & Education Center (TREC) at Portland State University

Camden Redevelopment Agency

City of Claremont

Municipality of Princeton (NJ)