If ever there was a doubt about the sheer depth and breadth of intersectionality found in the practice and theory of planning, the pandemic provides daily reminders.

At the beginning of 2020, Planetizen offered its annual list of trends to watch in the world of urban planning in the coming year. That post, and an accompanying video, made zero references to the looming threat of the coronavirus.

Looking back, the specific threat presented by the novel coronavirus should have been obvious in January, but most Americans, including us at Planetizen, were still unaware of how unprepared the country was for the coming public health crisis. Whatever it was that blinded us to the threat—blind faith, ignorance, a deeply ingrained belief in American exceptionalism—the country's response since the pandemic arrived on these shores has been unequivocally catastrophic, exacerbating every symptom and cause of American dysfunction along the way.

Despite the lack of a single mention of the likelihood of a pandemic, the "Urban Planning Trends to Watch in 2020" article still identified numerous factors with direct relevance to the way the pandemic played out in the United States.

The article did call attention, for example, to the movement to reclaim the public realm from car-centric planning. That trend found footholds in unexpected ways during the pandemic, of course, but some of the surprise comes from how much progress was achieved. Some cities, most notably New York, expanded bus priority to ensure quick, uncrowded transit service for essential workers. Outdoor dining programs (Al Fresco Streets, as Planetizen tended to call them) allowed businesses to operate through the pandemic in spaces that would had been strictly reserved for cars. Streets all over the country closed to automobile traffic to offer residents a place to exercise and get fresh air while everything else, including parks, closed. If your urbanism cause of choice is the effort to overturn auto dependence, 2020 was a success—though not an unequivocal success. Questions about the policing of public spaces and racial inequities in the allocation of resources forced a reckoning with the assumptions of many well-meaning urbanists.

Planetizen predicted that fare-free and fare-lite transit would be a major narrative in the coming year. It's true that in 2020, one major city, Los Angeles, began exploring the idea of offering free transit system wide, and another city, Columbus, extended an existing program to offer free transit to downtown workers. But transit ridership in 2020 was mostly defined by decline. Ridership plummeted on average for every transit system, and transit agencies are now facing a dire fiscal crisis. 2020 was defined by a sudden, deep decline in fare revenues, but not by choice.

Planetizen also predicted that sprawl and urbanism would play out a culture war in the Southwest this year, which ended up being true just about everywhere, and a theme discussed in much more detail below.

Finally, Planetizen predicted that homelessness would continue to be a political football, which turned to be true but in even scarier and more inhumane ways than imagined. While states and cities scrambled to prevent the pandemic from decimating homeless populations with only middling success, the aforementioned eviction crisis threatens to add many, many more unhoused people to the streets. One study earlier this year estimated that more than 20 million Americans could face evictions without protections and monetary support.

Planning and the Pandemic

Many people are looking to the field of planning and its allied professions for reassurance that there could be a silver lining in the pandemic experience, by somehow producing a better world after all this tragedy and struggle. While the words "Never waste a good crisis," have been bandied about like a marketing slogan all year, the pandemic has also forced a confrontation with how much of this crisis is the result of the opportunism, lack of foresight, and, yes, white supremacy that has shaped the built environment. While many planners and advocates are working to make sure that the legacy of the pandemic is positive for the long-term health, sustainability, and prosperity of the country and world, there are certainly no guarantees that we won't just collectively entrench the mistakes that got us here.

Planetizen has tracked the debate about how the pandemic is influencing planning throughout the year and will continue to do so for the foreseeable future. A few big, fundamental questions must be negotiated in the coming years and decades, but many of the confrontations with the pre-existing conditions of the built and natural environments have yet to produce a discernible, coherent response from those with the keys to planning processes—planners, politicians, academia, the media, and the public.

While many pundits and observers have preached caution and patience before jumping to conclusions about how the pandemic will play out for the economic and social health of communities around the country, ten months later, there is a lot evidence to evaluate—however incomplete—warnings to be issued, victories to be celebrated, and losses to be mourned. There's work to be done to recover from this tragic event in world history, and some of it can't wait.

Density and Infection; Pandemic Exodus

One of the first debates about planning's role in the pandemic was also its most intense and contentious. The assertion that density, and the infrastructure and built forms associated with urban living, hastens the spread of the coronavirus forced a confrontation with the most controversial and political issues of planning. Inevitably, much of the most opportunistic punditry from the early stages of the pandemic proved premature as the coronavirus spread to less dense, rural corners of the country. In the final few months of the calendar year, as the coronavirus spread to every corner of the United States, coalescing in an epicenter in one of the most fraught locations (from a planning theory perspective) in the whole country—Los Angeles—the debate has been amplified again.

Density has played such a central role in the discussion of the pandemic that it can be considered as both cause and effect. In terms of effect, the debate about whether density caused infections gave way to debate about whether the pandemic was causing a massive exodus from urban environments. Some signs of an urban exodus are apparent—rental prices in San Francisco and New York City have dropped precipitously, for example, home sales and housing prices in suburban and rural locations climbed. Murders are climbing at alarming rates in many cities. As the viability of working from home seemed like a much more tenable long-term professional option, "Zoom Towns" is another one of the marketing-friendly terms to drive the narrative about the potential for an urban exodus that harkens to the days of white flight in the 20th century. In December, some additional nuance is also essential. Home sales have stalled, and while residents are leaving San Francisco and New York, other large cities are booming, and many are holding steady.

The debate about long-term effect of the pandemic on the demographic and economic viability of dense, urban environments continues with as much fervor in December as it did in March and is likely to frame discussion about the pandemic for years and decades to come. In short, we are only just beginning the process of evaluating the outcomes of the pandemic on the built environment of the United States.

Racial Reckoning

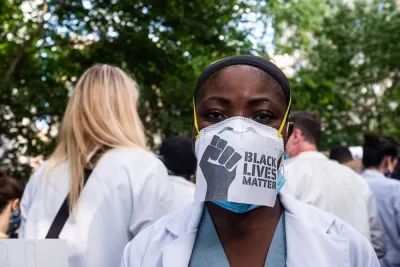

At almost every moment and in every twist and turn of the past year, the pandemic forced reckoning with matters of race and the ongoing inequities of the United States. It became evident early on that the Black and Latino Americans were getting infected and dying at rates widely disproportionate to their share of their population. The disparate public health impacts of the pandemic continue today, as do the mental health and economic effects. Clearly, the pandemic has only exacerbated the discriminatory and racist facts of life in the United States, before even considering the civil unrest that followed the police murders of George Floyd in Minneapolis, Breonna Taylor in Louisville, Ahmaud Arbery in Georgia, and others this year. Nationwide protests over police killings and systemic racism have continued for much of the year, leading to high-profile confrontations in places like Seattle and Washington, D.C. among countless other episodes of civil unrest and a new focus on the demands of the Black Lives Matter movement.

The intensity of the year's protests spurred a new push about the racist effects of contemporary planning—not just the legacy of past racist planning practices. Confrontations with the disparate outcomes of the pandemic and policing in the United States have revealed blind spots in the field of planning's awareness of the consequences of its actions. While many advocates for environmental and economic justice celebrated efforts to close streets to automobile traffic during the height of the stay-at-home orders in the spring and summer of this year, a growing number of planners and advocates pressed back, calling attention to the lack of inclusion in the decision-making process and the unintended consequences of those decisions.

Jay Pitter, Destiny Thomas, and Tamika Butler are just a few of the Black leaders at the forefront of this movement to center Black lives and people of color in a more equitable and inclusive approach to planning. Their work is already reshaping the field. The city of Oakland, California, for instance, rushed ahead of many of its peer cities in the effort to designate open streets during the spring, but faced criticism for a lack of representation in the process of making those decisions and in the outcomes of where those new amenities were located. As a result, the city completely overhauled its process with a new focus on equity and representation.

The gap between the experiences of the privileged and the impoverished have never been clearer than they have been during the pandemic. Media outlets as august as the Upshot at the New York Times, are leading with this point as the central narrative of their year-end editorial coverage. While some signs of reform are already visible, the question of whether the field of planning can achieve meaningful, lasting reform, and actively reverse its role in systemic racism, is still very much a question as the calendar prepares to turn to the second year of this pandemic.

This is part one of two in a series about the effects of the coronavirus pandemic on the field of planning—and vice versa. Part two will be published next week, with sections on the public realm, automobile dependence, direct action on homelessness, and affordable housing innovations. [Update: Part two can be found here.]

Maui's Vacation Rental Debate Turns Ugly

Verbal attacks, misinformation campaigns and fistfights plague a high-stakes debate to convert thousands of vacation rentals into long-term housing.

Planetizen Federal Action Tracker

A weekly monitor of how Trump’s orders and actions are impacting planners and planning in America.

San Francisco Suspends Traffic Calming Amidst Record Deaths

Citing “a challenging fiscal landscape,” the city will cease the program on the heels of 42 traffic deaths, including 24 pedestrians.

Defunct Pittsburgh Power Plant to Become Residential Tower

A decommissioned steam heat plant will be redeveloped into almost 100 affordable housing units.

Trump Prompts Restructuring of Transportation Research Board in “Unprecedented Overreach”

The TRB has eliminated more than half of its committees including those focused on climate, equity, and cities.

Amtrak Rolls Out New Orleans to Alabama “Mardi Gras” Train

The new service will operate morning and evening departures between Mobile and New Orleans.

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.

Heyer Gruel & Associates PA

JM Goldson LLC

Custer County Colorado

City of Camden Redevelopment Agency

City of Astoria

Transportation Research & Education Center (TREC) at Portland State University

Jefferson Parish Government

Camden Redevelopment Agency

City of Claremont