With better planning we can reduce disparities between drivers and non-drivers in their ability to access services and jobs, improving fairness and economic opportunities for disadvantaged groups.

Transportation planning is undergoing a paradigm shift — a change in the way problems are defined and potential solutions evaluated — from mobility-based to accessibility-based analysis. Mobility-based analysis assumed that our goal is simply to increase traffic speeds, so congestion is considered a major problem, and most transportation infrastructure funds are devoted to improving and expanding roads and subsidizing off-street parking. Accessibility-based analysis assumes that our goal is to improve access to desired services and activities, which can be achieved by increasing vehicle traffic speeds, improving non-auto modes, improving transportation system connectivity, increasing proximity through more development density and mix, improving transportation affordability, and through mobility substitutes such as telework and delivery services.

Accessibility-based planning expands the range of solutions that can be considered to solve transportation problems. For example, if a suburb-to-city roadway is congested, mobility-based planning assumes that the preferred solution is to expand it to accommodate more vehicles. Accessibility-based planning compares the costs and benefits of roadway expansion with other potential solutions: improving and encouraging space-efficient modes (bicycling, ridesharing, public transit), encouraging flextime and telework, and increasing suburban services and jobs, and urban housing options to reduce total peak-period traffic. When all impacts are considered, these solutions are generally most cost-effective and beneficial overall, particularly considering equity impacts.

A couple weeks ago I wrote a column, Planning for Accessibility: Proximity is More Important than Mobility, which used Walk Score and Urban Accessibility Explorer maps to compare the number of services and jobs accessible to drivers and non-drivers in various locations.

This analysis indicates that urban locations provide superior access to services and activities, particularly for non-drivers. It indicates that urban neighborhoods usually provide better accessibility by non-auto modes than rural and suburban locations provide to motorists, at a fraction of the cost. It shows that sprawl creates large disparities between drivers and non-drivers, and between wealthy travellers who can afford expensive transportation and lower-income travellers who are burdened by vehicle costs.

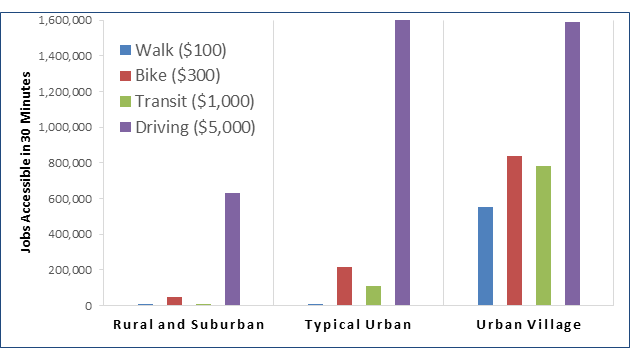

Here is more analysis of these issues. The graph below compares the typical number of jobs accessible by four modes in rural/suburban, typical urban neighborhoods, and urban villages (compact, mixed, walkable neighborhoods). Access to jobs is also a good indicator of access to services, since most services require workers.

Job accessibility by mode and location (Urban Accessibility Explorer Data)

This measures jobs, not employment opportunities; a typical job is only available every few years and most workers are most suitable for a limited range of jobs, so workers need thousands of jobs and employers need tens of thousands of workers within convenient commute distance for optimal economic performance. This helps explain why economic productivity and economic mobility (the likelihood that children in lower-income households become more economically successful as adults) tend to increase with density and multimodal accessibility; large numbers of jobs and workers allow better matches between workers’ abilities and employers’ needs. For that reason, high-accessibility neighborhoods can also be considered high-opportunity neighborhoods.

Below are key conclusions that can be drawn from this analysis:

- In rural and suburban areas non-drivers can access relatively few services and jobs. There may be a café or fast-food restaurant, barber- or beauty shop, or a small convenience store within walking or bicycling distance, but their variety and quality are usually limited.

- Urban locations generally offer orders of magnitude better access (typically tens of thousands of services and jobs within reasonable travel times), and have an order of magnitude lower travel costs (typically $100 to $1,000 annually for non-auto modes, compared with $5,000 to $10,000 annually to own and operate an automobile) than rural and suburban motorists.

- In rural and suburban areas, bicycling, including e-bikes, can provide far better accessibility than walking or public transit. Taking advantage of this potential requires planning to make bicycling safe and convenient.

This analysis shows once again that accessibility depends more on location than speed, particularly for non-drivers. Moving from sprawled, automobile-dependent areas to compact, multimodal neighborhoods improves accessibility far more than virtually any other transportation system improvement such as highway expansions, increased parking supply or reduced fuel prices.

Because accessible locations reduce disparities between drivers and non-drivers, and between higher- and lower-income travelers, policies that increase sprawl or discourage affordable infill are inherently unfair, regressive and economically harmful. Such policies include planning distortions that favor mobility over accessibility, limits on development density, and parking minimums that drive up urban housing costs. Describe more positively, Smart Growth policies that increase affordable housing in urban villages are a terrific way to achieve social equity goals in addition to their other benefits.

What do you think? How can we better communicate the benefits, including for social equity, provided by shifts from mobility- to accessibility-based planning?

Note: This analysis is based on a small sample. I would like to expand it to include more areas and destination types. Please contact me ([email protected]) if you are skilled in GIS analysis and are interested in collaborating on future research concerning driver-versus-non-driver accessibility disparities.

Planetizen Federal Action Tracker

A weekly monitor of how Trump’s orders and actions are impacting planners and planning in America.

Maui's Vacation Rental Debate Turns Ugly

Verbal attacks, misinformation campaigns and fistfights plague a high-stakes debate to convert thousands of vacation rentals into long-term housing.

San Francisco Suspends Traffic Calming Amidst Record Deaths

Citing “a challenging fiscal landscape,” the city will cease the program on the heels of 42 traffic deaths, including 24 pedestrians.

Amtrak Rolls Out New Orleans to Alabama “Mardi Gras” Train

The new service will operate morning and evening departures between Mobile and New Orleans.

The Subversive Car-Free Guide to Trump's Great American Road Trip

Car-free ways to access Chicagoland’s best tourist attractions.

San Antonio and Austin are Fusing Into one Massive Megaregion

The region spanning the two central Texas cities is growing fast, posing challenges for local infrastructure and water supplies.

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.

Heyer Gruel & Associates PA

JM Goldson LLC

Custer County Colorado

City of Camden Redevelopment Agency

City of Astoria

Transportation Research & Education Center (TREC) at Portland State University

Jefferson Parish Government

Camden Redevelopment Agency

City of Claremont