We are in perhaps the most dynamic period with respect to changes in travel behavior in the past 50 years. Chose your data wisely.

One of my favorite quotes about data is “More data does not help without more understanding.” attributable to Colin Harrison. Additionally, I have been known to argue, “Good data is critical to inform good decisions—and to embarrass bad ones.” While the cynic in all of us occasionally thinks that there are way too many decisions being made with no data, the wrong data, your data instead of my data, or in spite of the data, the majority of planning and policy professionals still strive to inform their work with new and objective data. For those involved in transportation planning, modeling, research, and policy, we have hit a sweet spot in terms of new data. Most significantly, the 2017 National Household Travel Survey data was released earlier this year, and analysts are turning that data into new knowledge about how travel is and is not changing. The first comprehensive national household travel data update since 2009, a partnership of the federal, state, and local governments has invested over $30 million and untold hours in producing this data set that will support planning and policy making for years to come.

The mystery of how aging millennials are traveling now, how technology is affecting trip making, how aging baby boomers are behaving regarding travel, and who is using app-based vehicle hailing services are among the questions we are anxiously awaiting answers to. The NHTS is the single best source for addressing these issues, because the multi-decade series of surveys is the most comprehensive set of information on household travel.

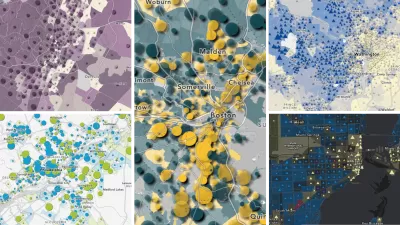

No data set answers all questions, so the NHTS will be used in conjunction with a host of other data sets to more comprehensively understand what is happening in travel. Each major national source has its own features and uses, collectively helping to form a comprehensive understanding of travel at the national level and, in many cases, the state or metropolitan area level. Other data sets at the state and local level can supplement these data sources and increasingly, BIG DATA is being used to fill in details and supplement our understanding of rapidly emerging trends, such as use of app-based vehicle hailing services.

Common National Transportation Survey Data Sources

National Household Travel Survey

- Federal Highway Administration (FHWA)

- 1969, 1975, 1983, 1990, 1995, 2001, 2009, and 2017.

The 2017 survey documents the demographic, attitudinal, and travel behavior for all members of 129,969 households. When statistically weighted to adjust for survey biases, the data demographically represents all Americans and is appropriate for analysis at the national and census region levels.

Access to data: https://nhts.ornl.gov/ and https://nhts.ornl.gov/tools.shtml.

American Community Survey

- U.S. Census Bureau

- 2005-2016. 2017 data due in mid-September 2018.

2,229,872 housing units and 160,572 group quarters were sampled. Information includes data on Commuting travel mode, time, vehicle ownership, and select demographics.

Access to data: https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/nav/jsf/pages/searchresults.xhtml?refresh=t

American Time Use Survey

- Bureau of Labor Statistics.

- 2003-2017. 2017 data now available.

Collected from over 190,000 interviews, this survey provides estimates of how, where, and with whom Americans spend their time. Activities include work and travel, but also include watching television and other activities typically foregone in other survey.

Access to data: https://www.bls.gov/tus/database.htm.

American Housing Survey

- U.S. Census Bureau.

- 1973-1981 annually. 1983-2015 biannually. 2017 data due in fall 2018.

115,398 housing units were sampled in 2015. This is the most comprehensive housing survey in the United States. The AHS surveys the same housings units biannually to obtain information on the quality of living as well as the size and composition of housing and characteristics of their accessibility.

Access to data: https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/ahs/data.html

OnTheMap

- U.S. Census Bureau.

- LEHD Origin-Destination Employment Statistics (LODES), 2002-2015.

This is an online mapping tool driven with administrative data that shows where workers are working and where they reside. In addition to geographic data on place of employment and residence, the tool provides select demographic and economic characteristics such as worker age, industry sector, and educational attainment among others.

Access to data: https://onthemap.ces.census.gov/.

Consumer Expenditure Survey

- Bureau of Labor Statistics.

1996-2016. 2017 data available in September 2018.

With 23,556 consumer units surveyed in 2015, this source provides data on expenditures, income, and demographic characteristics of consumers in the United States. This data set includes data on expenditures for transportation and housing as well as other activities.

Access to data: https://www.bls.gov/cex/data.htm

Census Transportation Planning Products

- American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials.

- 2006-2010 data available. 2012-2016 due early 2019.

This pooled fund program processes ACS data into information on geographic flows between geographies for understanding trip distribution. Using multiyear data sets allow for more geographic precision.

Access to data: https://ctpp.transportation.org/ctpp-data-set-information/5-year-data/

The good news is that these data sets—and this is not necessarily an exhaustive list—are getting more user friendly and more timely and there are increasingly powerful software tools to use in extracting, analyzing, and presenting the data.

In many ways, the NHTS data is still being unpacked and explored with additional supporting variables being added to the data set and web interface refinements being implemented, but some trends are emerging. In many cases, confirming study and peer review will help ensure proper interpretation of the data. And, as is always the case, the data is not perfect. Travel behavior is complex and difficult to communicate (i.e., is that ridesharing? app-based vehicle hailing, ridesourcing? using TNCs?, shared mobility?, or just a new name for taxi service?). Getting a representative sample is difficult, as is coaxing accurate information from an increasingly cynical, confidentiality conscious, and survey burdened public. And of course, the user community wants an ever-more-detailed picture of travel and context characteristics to support our research and understanding of travel. These demands result in over 300 variable in the NHTS data set.

What Are We Learning?

Perhaps the most significant and not surprising finding of the 2017 NHTS is that the downward trend in trip rates per capita appears to be continuing. As the figure shows, people are making fewer trips. When reviewing these data I look for three factors: findings consistent with a theory or our understanding of travel behavior, survey data evidence, and empirical and/or anecdotal evidence that is supportive of the observation. In the case of declining trip rates, there are a couple of supportive theories. People have historically traveled less as they age, and we are aging. Technology is enabling the substitution of communication for travel via any number of behaviors such as teleworking, e-commerce, social media networking in lieu of in person social interactions, distance learning, and electronic transfer of documents, media, music, information, and more. Survey evidence supports this finding, and the respective declines by trip purpose appear consistent with what one might expect given the mechanisms of substitution noted in the list. For example, e-commerce is growing at double-digit rates and could well account for the declines in shopping and running errands. Other empirical data support this proposition, as shopping centers report significant declines in foot traffic. Most video rental and music stores have long since gone out of business, and services such as online banking and bill paying have proliferated, in many cases replacing travel.

There is some evidence that survey method effect (the 2017 survey was predominately self-administered via web versus interview driven prior surveys) could have contributed, but the magnitude of change coupled with the theory and empirical data instill confidence that the trend is real.

Another thing we are learning more about is the role household based travel plays in the total travel on the roadway system. Interestingly, estimates of household-based travel are not keeping pace with the measured growth in roadway travel based on roadway volume counts. While work is still underway to understand the impacts of 2017 map measured distances versus prior respondent provided estimates, the survey data from household travel explains somewhere in the range of 66% to 73% of the total count of vehicle miles of travel from May 2016 through April 2017, the approximate survey data collection period. Other count data confirms that larger trucks and buses constitute about 10% of total traffic volume, leaving somewhere between 17% and 24% consumed by lighter duty commercial vehicles, delivery vehicles, police, fire, ambulance, utility service vehicles, persons such as realtors, Lyft drivers, and that pizza delivery guy that use personal vehicles for professional activities and don’t record all their travel in household surveys. Those trips to the bar, casino, or amour’s house that you might have forgotten to list on the household survey—and perhaps some long distance vacation trips, business trips, or others that tend to be left off daily surveys—might be part of the mystery mileage.

That is a lot of travel that we don’t know very much about. This share of travel has grown from about 14% in 2009 to the current 17% to 24% range. The magnitude of this change dwarfs some of the more subtle changes in personal travel behavior and begs a richer understanding of the totality of travel. This is particularly true in light of the fact that changes in person travel often have spillover effects. A decision to shop online may increase vehicle miles traveled (VMT) for delivery vehicles. Using a transportation network company service versus driving a personal vehicle could generate more total VMT. The stronger economy may result in households purchasing services as the household cleaning service, lawn service, eldercare service, pesticides service, the infamous pool guy, and others ramp up commercial travel—perhaps reducing the amount of travel and number of errands individuals carry out.

Over the next several months and years we will learn more about changing travel from these and other sources. There has been a tendency to extrapolate anecdotal evidence or limited context specific studies in early adoption locations to postulate broad national implications. Be careful, use the new data, and use it carefully. Stir in some common sense. We are in perhaps the most dynamic period with respect to changes in travel behavior in the past 50 years—but, travel behavior changes relatively slowly. Fixed land use, fixed transportation infrastructure, and extensive investment in transportation vehicles, personal habits, and other factors dampen the pace of change. Some of the changes at play may be transformational—but not always everywhere and not always right away.

For more early finding from the new NHTS click on the presentation and poster session links in the recent TRB/FHWA 2017 NHTS Workshop program.

Thanks for listening.

The opinions are those of the author – or maybe not – but are intended to provoke reflection and do not reflect the policy positions of any associated entities or clients. For questions or mobility policy research support contact [email protected].

Planetizen Federal Action Tracker

A weekly monitor of how Trump’s orders and actions are impacting planners and planning in America.

Map: Where Senate Republicans Want to Sell Your Public Lands

For public land advocates, the Senate Republicans’ proposal to sell millions of acres of public land in the West is “the biggest fight of their careers.”

Restaurant Patios Were a Pandemic Win — Why Were They so Hard to Keep?

Social distancing requirements and changes in travel patterns prompted cities to pilot new uses for street and sidewalk space. Then it got complicated.

Platform Pilsner: Vancouver Transit Agency Releases... a Beer?

TransLink will receive a portion of every sale of the four-pack.

Toronto Weighs Cheaper Transit, Parking Hikes for Major Events

Special event rates would take effect during large festivals, sports games and concerts to ‘discourage driving, manage congestion and free up space for transit.”

Berlin to Consider Car-Free Zone Larger Than Manhattan

The area bound by the 22-mile Ringbahn would still allow 12 uses of a private automobile per year per person, and several other exemptions.

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.

Heyer Gruel & Associates PA

JM Goldson LLC

Custer County Colorado

City of Camden Redevelopment Agency

City of Astoria

Transportation Research & Education Center (TREC) at Portland State University

Camden Redevelopment Agency

City of Claremont

Municipality of Princeton (NJ)