There are many ways that communities can support and encourage affordable housing development. Let's compare them.

Housing and transportation are most household's two largest expenditure categories, and are a major financial burden for many lower-income households. As a result, increasing housing and transportation affordability is an important planning objective. In recent years, planners have developed a better understanding of what this means and how to evaluate affordable housing development strategies.

What is Affordability?

Affordability refers to households' ability to purchase essential goods and services, and so depends on their ability to control costs, for example, to reduce housing and transport expenditures so more money is available for food, healthcare and education. Although all households want to save money—even wealthy households enjoy cheaper limousine fuel and discounted first-class airfares—affordability applies primarily to lower-income households that have difficulty purchasing basic goods. Not every household will take advantage of all money-saving opportunities, some may choose more expensive homes or vehicles than absolutely necessary for practical purposes, but the ability to save money increases affordability and economic security.

Households often make trade-offs between housing and transport costs, so it is important to consider them together: a cheap house is not truly affordable if its isolated location leads to high transportation costs, and a more costly house may be most affordable overall if located in an accessible, multi-modal neighborhood where transport costs are minimized. In the past, housing experts often defined affordability as households spending less than 30 percent of their budget on housing, including rents or mortgages, property taxes, maintenance and repairs, and basic utilities, but the newer approach defines affordability as households spending less than 45 percent of their budget on housing and transportation combined.

When evaluating affordability policies, it is important to recognize the diversity of demands, even among lower-income households. For example, some need larger houses, studios or home workshops, accommodation for people with disabilities, or garages for various vehicle types. Some lower-income households rely on walking and cycling, public transit, or automobiles, and many rely on a combination of these options. These demands often change over time, so affordable housing options should be flexible and responsive to changing needs.

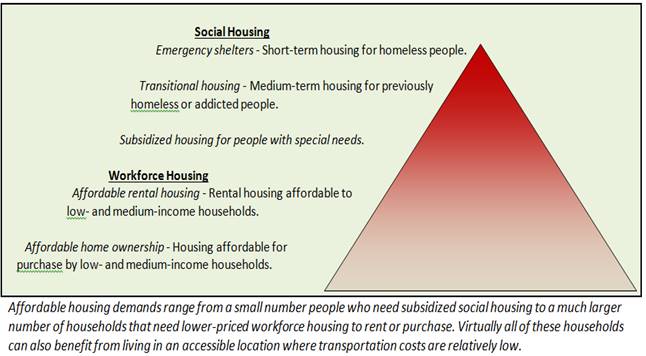

The term, affordable housing, refers to a wide spectrum of housing types, including homeless shelters and transition housing, subsidized social housing for people with special needs, and various housing types that low- and middle-income households can rent and purchase, as illustrated below.

The dynamic nature of housing prices can complicate affordability analysis. In particular, increasing the supply of middle-priced housing tends to increase affordable housing supply indirectly, as some households move from low- to the new middle-priced units, and over the long-term, as the new housing depreciates in price and becomes more affordable.

Let me describe a specific example of this. My city, Victoria, has a strong downtown that never had minimum parking requirements. About a decade ago, in response to a design charrette, the Downtown Core Area Plan eliminated parking requirements in an adjacent area, Harris Green. Since then, the downtown core has experienced significant new development, hundreds of new units, consisting largely of mid- and high-rise multi-family condominiums that sell for $200,000-500,000, which is a moderate price for Victoria, but not affordable.

However, after one of the projects was completed, a young neighbor who lived in a cheap old apartment on our street purchased one of the condominiums, which freed up an affordable rental unit. Had the city not reduced parking requirements there would be less downtown development, resulting in fewer moderate-priced condominiums that attract current renters and increase affordable units. This zoning code reform results in a more efficient real estate market that can respond to the growing consumer demands for urban housing; expanding these reforms to other urban neighborhoods, where land prices are lower, would further increase affordability.

Affordable Housing Strategies

Five common strategies for increasing housing affordability are described and compared below.

1. Maintain Older Housing

On average, houses depreciate 1-3 percent annually, which is good news for affordability in communities with an abundant supply of older but still functional houses. In such areas, providing affordable housing may involve helping low-income households repair and weatherize their homes to keep them safe and reduce utility bills. This may require subsidies or low-interest loans.

2. Government Subsidized Housing

Governments can sponsor and subsidize development of social housing to meet specific needs, such as seniors, people with disabilities, and low incomes. This is often the only way to serve unmet housing needs, and governments are often able to coordinate and mobilize resources unavailable to private developers, but it tends to have relatively high costs due to the complexity of government administration, and can generally serve only a small portion of total affordable housing demands.

Increasing rent subsidies in a market with limited affordable housing supply may favor some groups (those that qualify for the subsidy) to the detriment of others, and can contribute to rent inflation. For example, if city with 20,000 lower-income household but only 10,000 affordable housing units offers a new housing subsidy for people at risk of homelessness, low-income seniors, or people with certain disabilities, the recipients will benefit, but other groups, such low-income workers, college students, and people with disabilities that do not quality for the program will compete for fewer available units, forcing some to live elsewhere or pay more than they can afford, and the increased demand may allow property owners to raise rents more than would otherwise occur. Only if increased subsidies are implemented with policies that increase housing supply can all lower-income households benefit.

3. Urban Fringe Development

Public policies can encourage development on inexpensive urban-fringe land. Using mass production building techniques, developers can produce large numbers of relatively cheap housing, but sprawled development tends to have high infrastructure development costs and imposes high future transportation costs on residents and communities.

Such housing can be a curse to lower-income households, if after moving to an automobile-dependent area they experience an economic shock, such as reduced incomes, a vehicle failure or crash, or fuel price spikes. This explains why sprawled areas tend to have higher foreclosure rates than more central, multi-modal locations: improving transport options increases economic resilience.

Mexico's experience offers a useful cautionary tale about this type of development. Mexico established government programs that encouraged private developers to build large numbers of inexpensive single-family homes on converted farmlands. Because they are located at the urban fringe, these new communities have inadequate public services, and jobs are difficult to access. Residents bear high transportation costs and impose high traffic congestion, accident risk, and pollution emissions. Research suggests that this reduces overall economic productivity and opportunity. Most households are better off living in more central urban locations that provide better access and transport options.

4. Affordable Housing Mandates ("Inclusionary Zoning")

Inclusionary zoning requires developers to sell or rent a portion (typically 10-20 percent) of the units they build at below-market prices. Like Robin Hood, it forces higher-income households to cross-subsidize their lower-income neighbors. If required of all development in an area these cost are partly capitalized into land values, minimizing the burden on individual developers. However, this strategy is only successful if new housing demand is very strong, if not, developers build fewer units, particularly moderate priced units, which can result in less total affordable housing supply.

For example, if the cheapest housing units costs $200,000 to build, and regulations require 10 percent be priced at $100,000, each of the nine non-qualifying units bears an additional $11,111 ($100,000/9) cost, which adds about $20,000 to their final price, including overhead and financing costs. This is a small increase for high-priced housing (2 percent for a million dollar house) but a large increase for lower-priced housing (11 percent for a $200,000 condominium). Since lower-priced housing development tends to be price sensitive, this can significantly reduce the number produced. In this way, inclusionary zoning can reduce housing affordability, particularly over the long run, by reducing production of the moderately-priced houses that will be the future affordable housing stock.

5. Reduce Infill Development Costs

Allow and support owners of existing urban properties to increase density, for example, by converting a garage or basement into a rentable suite, adding a story, or replacing single-family with multi-family housing. Since wood-frame construction tends to be cheapest, and elevators add significant costs, the most affordable housing tends to be low-rise (two- to five-story) townhouses and multi-family, although mid-rise (five- to ten-story), and high-rise (more than ten story) buildings may be relatively affordable where land prices are very high. The Missing Middle refers to a variety of low-rise housing types that are particularly suitable for urban infill.

This development strategy typically involves policy reforms that allow smaller parcel sizes and subdivisions, support condominium and cooperative ownership structures, allow higher densities and building heights, reduce minimum parking requirements, and streamline the building approval process.

This tends to be the most cost effective overall, because it minimizes infrastructure and future transport costs, including residents' vehicle expenses, and indirect costs such as road and parking infrastructure requirements, congestion, accidents and pollution. By providing more affordable transport options that residents can use if needed, such as if they lose their job or their car breaks down, this strategy increases economic security.

In most cities there is large potential for affordable infill housing development, including moderate-priced development that becomes affordable over time, but such development can create local impacts (construction noise and dust, and increased vehicle traffic and parking problems), which lead to controversy and neighborhood resistance.

The table below compares these different strategies and identifies their most appropriate applications.

Comparing Affordable Housing Development Strategies

|

Description |

Advantages and Disadvantages |

Most Appropriate Applications |

|

Help homeowners maintain older housing stock |

Can be a relatively inexpensive way to provide safe and affordable housing. |

Where there is an abundant supply of inexpensive but deteriorating housing stock. |

|

Government sponsored and subsidized housing |

Serves special needs. Tends to be costly, and generally cannot meet the total demand for lower-priced housing. |

To serve special housing needs, including workforce housing where development costs are very high, such as in successful and attractive cities. |

|

Encourage abundant private development on inexpensive, urban-fringe land |

Can provide relatively inexpensive housing. Has high infrastructure and future transport costs, and so is not affordable overall. |

In cities where population growth justifies urban expansion, with planning to create complete and walkable new neighborhoods along utility and transit corridors. |

|

Affordable housing mandates |

Can create new affordable housing without government subsidy. Potential is generally modest, and unless housing demand is very strong will reduce total housing development, particularly middle-priced units. |

Only apply where housing demand is very strong to avoid reducing total development. |

|

Remove unjustified restrictions and costs for urban infill |

Tends to reduce the total costs of housing production, which increases total housing supply and allows markets to respond to demand. Impacts are unpredictable and may be slow. Infill development can impose costs and controversies. |

Apply wherever possible, and in conjunction with other strategies. |

Conclusions

Below are key conclusions of this analysis:

- Affordability analysis should be comprehensive, taking into account total housing costs (including utilities, taxes and maintenance) and transportation costs, considering both short- and long-run impacts.

- No single strategy can meet all affordable housing needs, most communities need a combination.

- Some lower-income households need help repairing and maintaining their homes.

- Government sponsored and subsidized housing is important to serve people with special needs, but can only address a small portion of total affordable housing demands.

- Urban fringe development can provide cheap housing but tends to have high infrastructure and future transportation costs, and so is only truly affordable if planned and located to maximize accessibility and transport options.

- Inclusionary zoning may provide a modest amount of affordable housing where demand is very strong, but should otherwise be avoided to prevent spoiling the market for new housing construction.

- Removing unjustified restrictions and costs for urban infill is generally the most cost-efficient and beneficial option overall, but is challenging due to local opposition, and because its benefits are widely dispersed and so has fewer advocates. Our challenge is to promote, Yes In My Backyard!

What do you think? Have I overlooked any important strategies? Are there other advantages and disadvantages to consider?

For More Information

Jonathan Ford (2009), Smart Growth & Conventional Suburban Development: Which Costs More? USEPA.

Jason Furman (2015), Barriers to Shared Growth: The Case of Land Use Regulation and Economic Rents, comments by the Chairman of the White House Council of Economic Advisers to the Urban Institute.

Erick Guerra (2015), “The Geography Of Car Ownership In Mexico City: A Joint Model Of Households’ Residential Location And Car Ownership Decisions, Journal of Transport Geography, Vol. 43, pp. 171–180.

Daniel Hertz (2016), Inclusionary Zoning has a Scale Problem, City Commentary.

Sanford Ikeda and Emily Washington (2015), How Land-Use Regulation Undermines Affordable Housing, Mercatus Center at George Mason University.

Melanie D. Jewkes and Lucy M. Delgadillo (2010), “Weaknesses of Housing Affordability Indices Used by Practitioners,”Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning, Vol. 21, No. 1, 2010.

Michael C. Lens and Paavo Monkkonen (2016), “Do Strict Land Use Regulations Make Metropolitan Areas More Segregated by Income?” Journal of the American Planning Association, Vol. 82/1, pp. 6-21; summary at www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/01944363.2015.1111163?journalCode=rjpa20.

Todd Litman (2016), Affordable-Accessible Housing In A Dynamic City: Why and How To Support Development of More Affordable Housing In Accessible Locations, Victoria Transport Policy Institute.

Location Affordability Portal is an information resource to help households evaluate trade-offs between transportation and housing costs.

William H. Lucy and Jeff Herlitz (2009), Foreclosures in States and Metropolitan Areas: Patterns, Forecasts, and Pricing Toxic Assets, University of Virginia.

Michael Manville (2010), Parking Requirements as a Barrier to Housing Development: Regulation and Reform in Los Angeles, Report UCTC-FR-2010-03, University of California Transportation Center.

Ed Murray (2015), Housing Seattle: A Roadmap to an Affordable and Livable City, Mayor’s Office, City of Seattle.

PSRC (2015), Complete Housing Toolkit, Puget Sound Regional Council.

Rachel Quednau (2016), The Cost of Commuting vs. Living Close, Strong Towns Journal.

Kyle Russel (2014), “This One Intersection Explains Why Housing Is So Expensive In San Francisco,” Business Insider.

Mac Taylor (2015), California’s High Housing Costs: Causes and Consequences, Legislative Analyst’s Office.

Mac Taylor (2016), Perspectives on Helping Low-Income Californians Afford Housing, Legislative Analyst’s Office.

Planetizen Federal Action Tracker

A weekly monitor of how Trump’s orders and actions are impacting planners and planning in America.

Map: Where Senate Republicans Want to Sell Your Public Lands

For public land advocates, the Senate Republicans’ proposal to sell millions of acres of public land in the West is “the biggest fight of their careers.”

Restaurant Patios Were a Pandemic Win — Why Were They so Hard to Keep?

Social distancing requirements and changes in travel patterns prompted cities to pilot new uses for street and sidewalk space. Then it got complicated.

Platform Pilsner: Vancouver Transit Agency Releases... a Beer?

TransLink will receive a portion of every sale of the four-pack.

Toronto Weighs Cheaper Transit, Parking Hikes for Major Events

Special event rates would take effect during large festivals, sports games and concerts to ‘discourage driving, manage congestion and free up space for transit.”

Berlin to Consider Car-Free Zone Larger Than Manhattan

The area bound by the 22-mile Ringbahn would still allow 12 uses of a private automobile per year per person, and several other exemptions.

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.

Heyer Gruel & Associates PA

JM Goldson LLC

Custer County Colorado

City of Camden Redevelopment Agency

City of Astoria

Transportation Research & Education Center (TREC) at Portland State University

Camden Redevelopment Agency

City of Claremont

Municipality of Princeton (NJ)