The new International Housing Affordability Survey contains various errors and biases. The author even claims that compact housing reduces fertility. Really? Smart policies can create affordable and family-friendly housing.

Wendell Cox and Hugh Pavletich recently released their latest International Housing Affordability Survey (IHAS), which compares single-family housing prices with incomes for various cities around the world. It is the only free source of this information, and so is widely cited by news media.

The authors have a clear political agenda: they criticize Smart Growth policies that support more compact urban development (they even argue that it reduces fertility, as discussed below) and advocate lower-density, sprawled development. The Survey's analysis and text is structured to support this ideology.

I criticized the Survey's methods in previous blogs, including "How Not to Measure Housing Affordability," "What is a 'House'? Critiquing the Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey," and "More Critique of Demographia's International Housing Affordability Survey," and tried to raise my concerns directly with the authors, but the new edition continues their previous omissions and biases. It is important that anybody who uses the Survey results understands these problems, as discussed in this column.

Ignores Transportation Costs

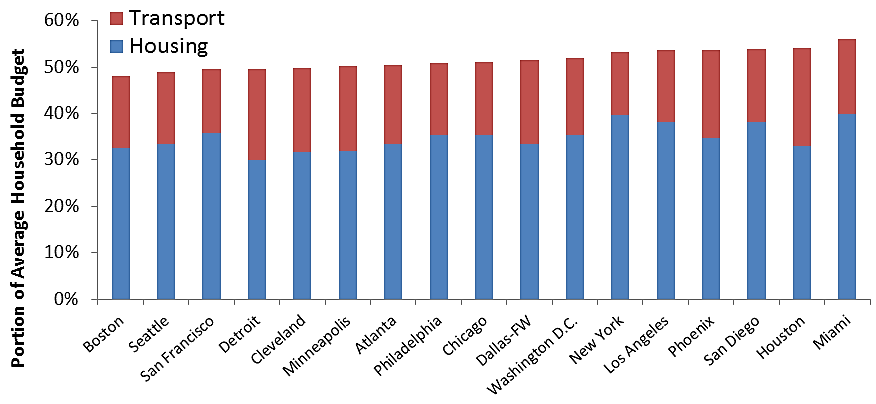

The IHAS analysis only considers housing expenses, ignoring transportation costs. This is important because households often make trade-offs between these costs: a cheap house is not really affordable if located in an area with high transportation costs. Various studies indicate that more accessible, multi-modal neighborhoods tend to be most affordable overall, considering both housing and transportation costs.

The graph below illustrates this: many of the cities that Cox and Pavletich criticize for high housing prices, such as Boston, Seattle and San Francisco, are actually more affordable overall than the sprawled regions he celebrates, such as Phoenix, Houston, and Miami, because their higher housing costs are more than offset by cheaper transport. This effect is even more dramatic when evaluated at a neighborhood scale.

Household Spending on Housing and Transport By Urban Region

Households in the compact regions that Cox criticizes as unaffordable, such as Boston, Seattle, and San Francisco, spend less in total on housing and transport than in the sprawled regions he advocates, such as Phoenix, Houston, and Miami, because their higher housing costs are more than offset by cheaper transport.

Only Considers Single-Family Housing

The IHAS analysis only considers single-family housing, even in cities where other housing types are more common. For example, the IHAS rates Vancouver, Canada as one of the world's least affordable cities due to its high single-family housing prices, although they only represent 18 percent of total housing units. As a result, the Index greatly exaggerates the region’s housing costs.

|

|

Single-Family |

Attached |

Apartments |

|

Vancouver City |

47,535 (18%) |

59,340 (22%) |

157,695 (60%) |

|

Vancouver Region |

301,140 (34%) |

232,360 (26%) |

357,840 (40%) |

The IHAS analysis only considers single-family housing prices, which exaggerates housing costs in cities such as Vancouver where most housing units are attached or apartments.

The graph below shows Vancouver's housing price trends. The red and green lines indicate large increases in single family-housing prices, while the orange and purple lines show much lower price increases for townhouses and apartments. Vancouver, is a rapidly-growing, attractive, economically-successful, and geographically constrained city, so single-family housing is expensive, but townhouses and apartments are relatively affordable.

Vancouver Benchmark Housing Prices

Vancouver region single-family housing prices increased significantly during the last five years, but townhouse and apartments are relatively affordable.

Cox and Pavletich never specifically state that their survey only considers single-family housing, I inferred that by analyzing their results, as discussed in my previous blogs, What is a 'House'? Critiquing the Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey. To be accurate they should clarify that when they write "house" they refer only to single-family housing, and if they want to be transparent, they should make their data available for peer review, which is standard practice for any serious academic study.

Ignores Other Geographic Factors Affecting Housing Supply

The IHAS ignores important factors that affect land availability and therefore housing prices. Virtually all of the cities Cox and Pavletich criticize as unaffordable are attractive, economically successful, and geographically constrained—they are limited in their ability to expand by water bodies, mountains, and inflexible legal boundaries, while the cities they celebrate as affordable are less attractive and less constrained. Geographically constrained cities must grow inward and upward, that is their destiny, but Cox and Pavletich argue that they must grow outward. What are they thinking?

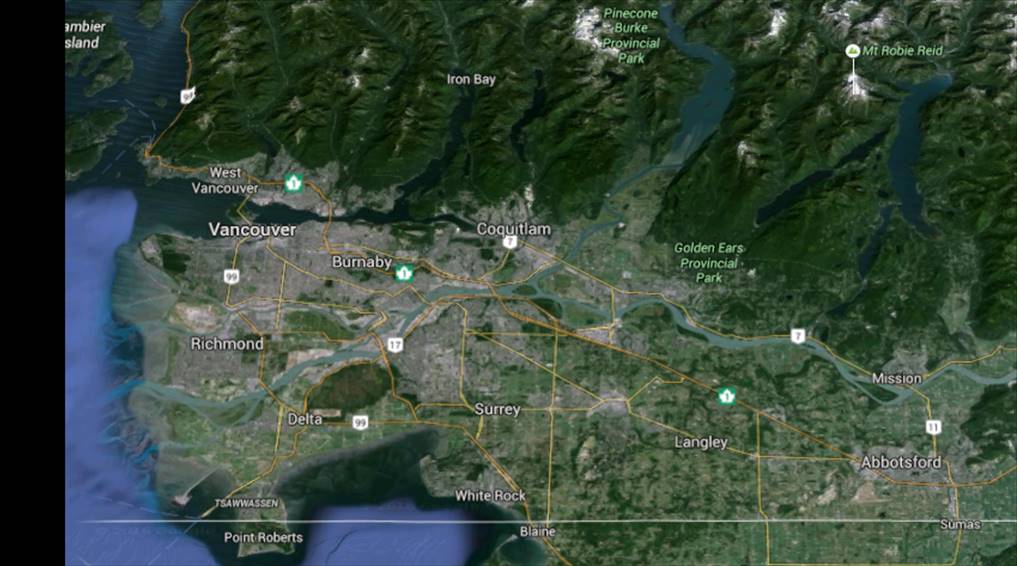

Consider Vancouver, for example: to the west is the ocean, north are mountains, south is the U.S. border, and east is some of Canada's most valuable farmland. There no abundant supply of developable land within convenient commute distance of the city; there may be a few hundred urban fringe hectares available, but nowhere near the amount land needed to accommodate the hundreds of thousands of additional households that want to locate in the Region, and urban fringe development has high infrastructure and transportation costs, so such housing cannot be truly affordable. Most other cities that Cox and Pavletich criticize for their high single-family housing prices are similarly constrained.

The Vancouver Region

Economic Opportunity and Mobility

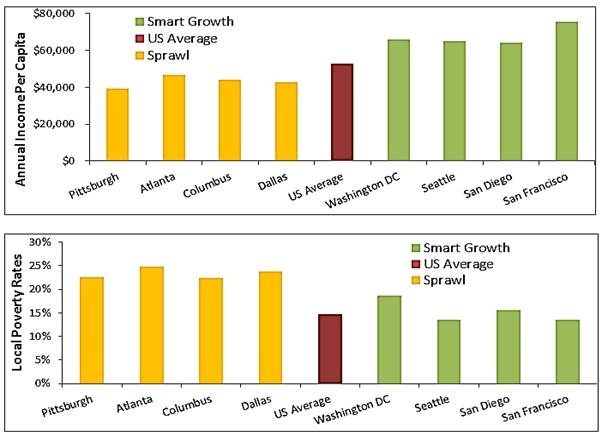

Cox and his colleague Tory Gattis argue that sprawl increases economic opportunity by allowing more lower-income households to purchase their homes, but their claims cannot stand scrutiny. In fact, the sprawled urban regions that Cox cites as examples to emulate, such as Pittsburgh, Atlanta, Columbus, and Dallas, have far lower average incomes and higher poverty rates than the U.S. average, while cities that he criticizes for their Smart Growth policies, including Washington, D.C., Seattle, San Diego, and San Francisco, have higher average incomes, lower poverty rates, higher education attainment, lower housing foreclosure rates, and greater economic mobility (chance that a child born into a low-income household will be economically successful as an adult) than the compact regions he criticizes.

Income and Poverty Rates Compared

International Housing Affordability and Ownership Analysis

A recent book, Zoned In The USA, by Professor Sonia Hirt provides more good evidence that the pro-sprawl policies that Cox and Pavletich advocate actually reduce housing affordability and economic opportunity. Hirt analyzes zoning codes between different countries, which provides a natural experiment for testing their impacts.

Despite low urban densities, high automobile ownership, low fuel prices, and generous mortgage tax deductions, the United States has lower home ownership rates than peer countries: 65 percent of U.S. housing is owner-occupied, compared with 67 percent in Australia, 68 percent in Canada, and 70 percent for the European Union average. In addition, 45 percent of U.S. houses have a mortgage, compared with just 27 percent in the European Union, further indicating that sprawl-based policies that encourage lower-density urban-fringe development fail to increase home ownership. The major difference between the United States and other democracies is that a larger portion of Americans live in detached houses in lower-density, automobile-dependent neighborhoods, while other countries have more compact housing (e.g., rowhouses and multi-family) located in multi-modal neighborhoods, which tends to be more affordable overall, considering both housing and transport expenses.

Hirt argues that North America’s higher rates of single-family housing result not from difference in consumer preferences, but rather from restrictive policies such as zoning codes that effectively prohibit more compact housing types in most urban neighborhoods. According to her analysis, the overwhelming majority of residential land is reserved for single-family houses, and no U.S. city in which more than 3 percent of the land is zoned for mixed use. These regulations are far more restrictive than in European cities. For example, most of Paris is in a "General Urban" zone, which allows "a startling variety of establishments, including houses, apartment buildings, shops, restaurants, cafes and offices."

These restrictions on urban density and mix have several measurable, undesirable outcomes: not only does the United States have significantly lower home ownership rates, it also has higher portion of household budgets devoted to transport, higher traffic fatality rates, higher obesity rates, and fewer transport options, and therefore less economic opportunity, for non-drivers. Described differently, Smart Growth policies provide numerous economic, social and environmental benefits.

In fact, a Forbes magazine article, In World's Best-Run Economy, House Prices Keep Falling -- Because That's What House Prices Are Supposed To Do, describes how the German economy is able to maintain housing affordability through regulations that include strict limits on urban sprawl and housing prices, belying Cox and Pavletich's claims that urban containment policies always lead to excessive housing prices.

Rysum, Germany, a 15th-century village. Expansion is restricted within a growth boundary, creating a sharp urban and rural edge.

Smart Affordable Housing Strategies

The most affordable types of housing to develop tend to be townhouses and low-rise apartments with unbundled parking, since they minimize land requirements per unit, have low construction costs (for example, the 2015 Building Valuation Data Report indicates that basic wood-frame R-2 multi-family housing costs $119 per square foot, compared with $125 per square foot for R-3 single-family housing), lets households avoid paying for unneeded parking spaces, which can reduce housing costs by an additional 10-20 percent, and by sharing walls, tends to minimize utility costs. Anybody who truly cares about housing affordability should encourage the development of such housing, so it is available for any household that demands it, but Cox and Pavletich only advocate single-family housing development.

Ignores Other Sprawl Costs

Cox and Pavletich ignore the true costs of sprawl to residents and communities, including significant increases in traffic accident injury and death rates, reduced physical fitness and health, reduced economic resilience (they have fewer responses to financial stresses such as reduced income or a vehicle failure) resulting in higher housing foreclosure rates, reduced mobility options for non-drivers and resulting increases in chauffeuring burdens, and reduced economic mobility (the chance that lower-income children will become economically successful as adults).

Smart Growth Reduces Fertility?

In a Vancouver Sun interview Cox suggests that high housing prices reduce fertility rate, saying, "A lot of people don’t want to raise children on the tenth floor of a condominium." Really? Smart Growth is a birth control strategy?

Although Cox provides no credible evidence that compact housing actually reduces fertility, or that this is a problem in a world strained by population growth, let's accept his premise and consider some smart strategies for creating more fertile urban housing.

Contrary to critics claims, Smart Growth does not generally require most families to live in high-rise; my research indicates that in most cities, excepting those that are very geographically constrained, approximately equal portions of small-lot single-family, attached, and multi-family housing (mostly mid-rise) can achieve Smart Growth benefits including openspace preservation, efficient public infrastructure, transportation and affordable housing, traffic safety, public fitness and health, and pollution emission reductions. This generally means that people live in apartments as young adults, single-family or attached housing when they have children, and attached or apartment housing as seniors. I see nothing wrong with raising children in tenth-story apartments, but but that is not required for compact urban development.

Several good studies have investigated ways to make urban neighborhoods more family friendly. For example, a Federal Reserve Bank study, Linking Transit-Oriented Development, Families and Schools, recommends incorporating schools, daycare centers and parks, and improving pedestrian conditions. The Mixed-Income Transit-Oriented Development Action Guide provides practical guidance for developing diverse housing options that are affordable to a range of incomes, for people at different stages of life, in compact, multi-modal neighborhoods. The Center for Cities & Schools report Families and Transit-Oriented Development: Creating Complete Communities for All identifies ways that complete communities can serve families with children, and the benefits that result.

Strategies for family-friendly Smart Growth:

- Ensure that neighborhoods have options for basic shopping including groceries, pharmacies and school supplies.

- Investment in parks, libraries, and neighborhood events to help create a sense of community

- Improve streetscapes and bicycle and pedestrian conditions to create streets where young people can safely walk and play.

- Integrate schools into the community.

- Develop high-quality transit services that provides access to regional employment opportunities.

- Provide affordable access to regional amenities such as zoos and large parks.

Benefits of more family-friendly Smart Growth:

- Household transportation cost savings from reduced need to own and operate vehicles.

- Reduced childhood obesity through increased physical activity.

- Reduced family stress through shorter commute times and more family activity time.

- Improved educational outcomes through access to stable housing and a range of supportive and enriching activities.

- Improved access to youth economic opportunities and mobility.

Inaccurate Diagnosis Leads To Inappropriate Prescriptions

Cox and Pavletich are sprawl advocates and Smart Growth critics, so their analysis jumps to the conclusion that all community problems—high housing prices, income inequity, and low central city fertility rates—result from urban containment policies. Their solution is more sprawl. I believe that their diagnosis is only partly correct and their prescription is wrong.

It is true that a combination of urban containment, either natural or regulatory, in conjunction with restrictions on compact infill, often drive up housing prices in attractive, economically successful cities. The IHAS includes statements such as, "The largest losses in housing affordability have been associated with urban containment policy," although it provides no evidence that this is the primary cause. In fact, extensive research, including studies cited by Cox, indicate that high housing prices in economically successful and geographically-constrained cities, such as Vancouver, San Francisco, Boston, and New York, are primarily caused by regulatory constraints on compact urban infill, such as limits on development density, building height and mix, burdensome regulatory requirements on urban development, plus minimum parking requirements.

Cox and his colleagues are blind to these constraints on compact infill, and ignore the additional costs to households and communities of sprawl. Their preferred solution—more low-density urban fringe development—will create a new set of problems, including higher total housing and transport costs to households that locate in automobile-dependent areas, an issue they never address.

I've raised these concerns in direct correspondence with Cox and Pavletich and previous blogs but they have not responded or improved their analysis. This is unfortunate. The current IHAS is little more than pro-sprawl propaganda; if it were more comprehensive and less biased, it could be a useful tool for some types of analysis.

This is not to deny that affordability is important, I’m a strong supporter of policies that increase true affordability, but Cox and Pavletich do their readers a disservice by ignoring the complexities of these issues.

For More Information

Cherise Burda and Mike Collins-Williams (2015), Make Way For Mid-Rise: How To Build More Homes In Walkable, Transit-Connected Neighbourhoods, GTA Housing Action Lab.

Alex Cecchini (2015), Barriers to Small Scale Infill Development, Streets MN.

CNT (2008), Housing + Transportation Affordability Index, Center for Neighborhood Technology.

CTOD (2015) Mixed-Income Transit-Oriented Development Action Guide, Center for Transit-Oriented Development.

Kim-Mai Cutler (2014), How Burrowing Owls Lead To Vomiting Anarchists (Or SF’s Housing Crisis Explained), Techcrunch.

Jonathan Ford (2009), Smart Growth & Conventional Suburban Development: Which Costs More? U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

Edward L. Glaeser and Bryce A. Ward (2008), “The Causes And Consequences Of Land Use Regulation: Evidence From Greater Boston,”Journal of Urban Economics, Vol. 65, pp. 265-278.

Daniel Hertz (2015c), Journalists Should Be Wary Of “Median Rent” Reports, City Observatory.

Mark Hogan (2014), “The Real Costs Of Building Housing: An Architect Shows The Real Costs Of Building In The Country’s Most Expensive City,”The Urbanist, Vol. 530.

A-P Hurd (2014), How Outdated Parking Laws Price Families Out of the City: Bundling Parking With Living Space Structurally Raises The Cost Of Urban Life, City Lab.

Sanford Ikeda and Emily Washington (2015), How Land-Use Regulation Undermines Affordable Housing, Mercatus Center at George Mason University.

Michael C. Lens and Paavo Monkkonen (2016), “Do Strict Land Use Regulations Make Metropolitan Areas More Segregated by Income?”Journal of the American Planning Association, Vol. 82/1, pp. 6-21.

Let’s Go LA (2014), Dingbat Renaissance.

Michael Lewyn and Kristoffer Jackson (2014), How Often Do Cities Mandate Smart Growth or Green Building?Mercatus Center (www.mercatus.org), George Mason University; at http://bit.ly/1E44vKc.

Todd Litman (2015), Affordable-Accessible Housing In A Dynamic City: Why and How To Support Development of More Affordable Housing In Accessible Locations, Victoria Transport Policy Institute.

Tim Loomans (2015), Five Ways to Add Density Without Building Highrises, Blooming Rock.

Michael Manville (2010), Parking Requirements as a Barrier To Housing Development: Regulation and Reform In Los Angeles, UCLA Institute of Transportation Studies.

Gregory L. Newmark and Peter M. Haas (2015), Income, Location Efficiency, and VMT: Affordable Housing as a Climate Strategy, California Housing Partnership and Center for Neighborhood Technology.

Dan Parolek (2014), Missing Middle Housing: Responding To Demand For Walkable Urban Living, Opticos Design/Missing Middle.

Stephanie Pollack, Barry Bluestone and Chase Billingham (2010), Maintaining Diversity In America’s Transit-Rich Neighborhoods: Tools for Equitable Neighborhood Change, Dukakis Center for Urban and Regional Policy.

Portland (2014), Infill Design Project, Portland Bureau of Planning and Sustainability.

Regulatory Barriers Clearinghouse describes affordable housing policy reforms.

SPUR (2014), 8 Ways to Make San Francisco More Affordable: Proposals To Solve The Housing Affordability Crisis, SPUR.

Mac Taylor (2015), California’s High Housing Costs: Causes and Consequences, Legislative Analyst’s Office.

Stockton Williams (2015), Preserving Multifamily Workforce and Affordable Housing: New Approaches for Investing in a Vital National Asset, Urban Land Institute.

Planetizen Federal Action Tracker

A weekly monitor of how Trump’s orders and actions are impacting planners and planning in America.

Chicago’s Ghost Rails

Just beneath the surface of the modern city lie the remnants of its expansive early 20th-century streetcar system.

San Antonio and Austin are Fusing Into one Massive Megaregion

The region spanning the two central Texas cities is growing fast, posing challenges for local infrastructure and water supplies.

Since Zion's Shuttles Went Electric “The Smog is Gone”

Visitors to Zion National Park can enjoy the canyon via the nation’s first fully electric park shuttle system.

Trump Distributing DOT Safety Funds at 1/10 Rate of Biden

Funds for Safe Streets and other transportation safety and equity programs are being held up by administrative reviews and conflicts with the Trump administration’s priorities.

German Cities Subsidize Taxis for Women Amid Wave of Violence

Free or low-cost taxi rides can help women navigate cities more safely, but critics say the programs don't address the root causes of violence against women.

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.

planning NEXT

Appalachian Highlands Housing Partners

Mpact (founded as Rail~Volution)

City of Camden Redevelopment Agency

City of Astoria

City of Portland

City of Laramie