Preserving urban landscapes can be just as important as preserving historic buildings. However, saving our design heritage needs to be balanced with the imperative that places effectively meet the functional needs of contemporary cities.

Urban landscapes seem to barely register on the radar of most historic preservationists. Maybe famous ones in big cities attract some attention, but it is typically the traditional gardens, private estates, and lushly planted parks – places that fit a preconceived notion of what historic landscapes should look like – that people care about. Less conventional places, such as hardscape-heavy urban parks, plazas, and squares present more of a challenge. The problem is more basic than just convincing people that a place is worthy of preservation. What it really comes down to is whether landscapes in ever-evolving cities can – or should – be preserved at all.

Let’s assume for a minute that historic urban landscapes should be preserved – if architects can have their work saved, why can’t the same be true for landscape architects? Well, for one, the practical process of historic preservation is decidedly building-centric and dominated by a vocabulary focused on architectural details like cornices, eaves, porches, and windows. This puts landscapes at a disadvantage since they are dealt with using broad-brushed, generic criteria that makes it impossible to apply any consistent application across the various types. While you cannot expect to craft any meaningful, apples to apples comparison between buildings and landscapes since they are so inherently different, it would be nice if the playing field was a little more even.

Buildings are essentially objects – coherent (usually) arrangements of walls, roofs, doors, and windows – and are easily identified as such. Of course they can be wildly and wonderfully different from one another, but what you see is generally what you get, and, as static objects, they can be preserved, as is, pretty much forever. Landscapes, on the other hand, are ephemeral and, by nature, constantly evolving. Therefore, you really can’t apply a strict use of the term preservation to them the way you can with a painting, sculpture or building. While this means they are more dynamic, it is also why they can be so hard to justify as places to save, especially as design expressions, since they will inevitably look different over time.

In the same way that there are a lot of modernist, Brutalist and even postmodernist buildings attracting attention from preservationists, there is a slew of significant – and not so significant – works of midcentury landscape architecture coming of age in our cities, as well. These represent a mixed bag of quality as contemporary places, but do embody a period of time during which the look and function of our urban realm was dramatically changed and, therefore, at least according to some, deserve to be saved. And I agree with this…usually.

I passionately believe that the legacy of landscape architecture and urban design in the making of American cities needs to be recognized, since the history of our public realm – the space between buildings – is at least as important as that of the buildings themselves. However, this should not be a mandate. Saving our design heritage needs to be balanced with the imperative that urban landscapes effectively meet the functional needs of contemporary life. You cannot always do both.

This conundrum played out in Minneapolis recently with the successful effort by the Preservation Alliance of Minnesota and the Cultural Landscape Foundation (TCLF) to save Peavey Plaza – the concrete laden, late modernist sunken plaza designed by the landscape architect Paul M. Friedberg – from the wrecking ball. It was undoubtedly a victory for preservation, but I am not convinced history is going to prove it to be the best thing for Minneapolis.

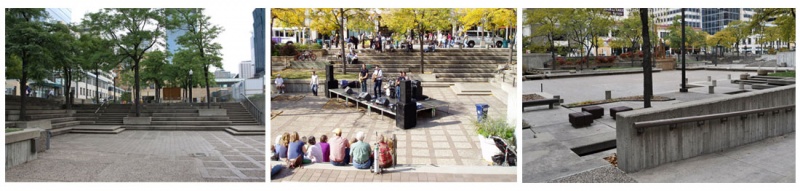

Keep in mind that I am no expert on Peavey Plaza. I have seen it beautifully photographed on summer days, when the light is perfect and kids are playing in the fountain, and it looks delightful. My experience, however, which is based on three separate visits to Minneapolis in both summer and fall, is quite different. Except for one afternoon when a festival was underway, the space seemed woefully underused. And on drab chilly days, the lack of energy and mass of gray concrete made the place downright dreadful. It was at these times, when empty, that the awkward relationship between the space and its urban context – as it steps down away from the street – was most apparent. They may be unique design features, but there is a reason we don’t see these kinds of concrete bathtubs being built anymore: they don’t make great places.

This being said, it really doesn’t matter what I think…at least not in this case. Even though it is perfectly legitimate to challenge the placemaking value of any urban landscape, no one’s particular aesthetic judgment should influence the process of saving historic landscapes or buildings – that is the whole reason objective criteria are created. If we only preserved things that fit our current ideals for quality then we would lose much of the precedent upon which contemporary design has been built.

The agreed upon solution for Peavey Plaza will provide modest updates while allowing its original design integrity to remain largely intact – displaying the sort of compromise TCLF has become known for. The organization has been the real leader in promoting both the need to save these types of landscapes and the understanding that allowing historic places to be updated, at least a little, and in a responsible manner, is often the best solution.

The alternatives to this kind of designed evolution are 1) Pure preservation – which is hard to pull off effectively due to the changing nature of landscape – and 2) Completely starting over with a new design. This is the approach Jacob Javits Plaza in lower Manhattan has taken several times over the past twenty years. The most recent change turned the pop art plaza designed by the landscape architect Martha Schwartz – itself a direct response to an earlier design anchored by a controversial Richard Serra sculpture – into a neo-modern, Roberto Burle Marx-esque landscape designed by Michael Van Valkenburgh Associates. There did not seem to be much heartache over the removal of Schwartz’s version of the space, and time will tell whether or not the new iteration will last any longer than the others.

Although it may seem harsh to keep ripping out designs and redoing them, there is some logic to the approach since it keeps the space fresh and responsive to current needs…even if it never becomes a cherished place. As with all of historic preservation, it really comes down to advocacy. If no one cares whether a place is lost, then chances are it eventually will be.

These issues are not just for famous places or big cities to deal with; towns and cities across the country contain all sorts of funky plazas and spaces that may lack an impressive design pedigree but still contribute a great deal to the urban fabric. Whether these spaces are saved or not, it will be increasingly important for preservationists, planners and community leaders to develop better tools with which to evaluate urban landscapes effectively and fairly as both reflections of history and successful contemporary places before determining their fate.

Planetizen Federal Action Tracker

A weekly monitor of how Trump’s orders and actions are impacting planners and planning in America.

Map: Where Senate Republicans Want to Sell Your Public Lands

For public land advocates, the Senate Republicans’ proposal to sell millions of acres of public land in the West is “the biggest fight of their careers.”

Restaurant Patios Were a Pandemic Win — Why Were They so Hard to Keep?

Social distancing requirements and changes in travel patterns prompted cities to pilot new uses for street and sidewalk space. Then it got complicated.

Platform Pilsner: Vancouver Transit Agency Releases... a Beer?

TransLink will receive a portion of every sale of the four-pack.

Toronto Weighs Cheaper Transit, Parking Hikes for Major Events

Special event rates would take effect during large festivals, sports games and concerts to ‘discourage driving, manage congestion and free up space for transit.”

Berlin to Consider Car-Free Zone Larger Than Manhattan

The area bound by the 22-mile Ringbahn would still allow 12 uses of a private automobile per year per person, and several other exemptions.

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.

Heyer Gruel & Associates PA

JM Goldson LLC

Custer County Colorado

City of Camden Redevelopment Agency

City of Astoria

Transportation Research & Education Center (TREC) at Portland State University

Camden Redevelopment Agency

City of Claremont

Municipality of Princeton (NJ)