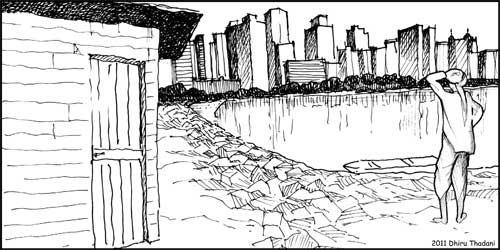

This famous statement by Mahatma Gandhi is being challenged by urbanists today who see a shining future for India in its cities. Architect Dhiru Thadani writes that Gandhi's vision of village life can apply to all levels of urban form.

"The future of India lies in its villages"

On two recent occasions I have heard references to this sage assertion by Mahatma Gandhi. The first reference was made by an Indian developer blaming this statement for the narcolepsy that politicians have displayed toward the value of Indian cities. The developer's underlying idea was that if politicians cared about the city they would eliminate height and floor-area restrictions on property in land-starved Mumbai.

The second reference was made by a fast-talking Harvard University professor of economics who declared that Gandhi was certainly wrong in making this statement and that India's future depended on its cities. The professor's thesis was that the unapologetic mass-construction of high-rise structures on every underutilized urban site would increase supply, and he presumes (erroneously) that this would reduce the cost of home ownership.

Troubled by these proclamations, one from business and one from academia, I decided to look deeper into the Mahatma's statement.

Although Jawaharlal Nehru and Mahatma Gandhi struggled together to attain India's independence, it was believed that their visions for their homeland's future differed significantly. Both men had been deeply affected by the poverty and human degradation that they had experienced in rural India.

Prime Minister Nehru's vision for an independent India relied heavily on industrialization and the building of material prosperity. As a consequence, the city was the conduit for trading these material goods. Although well aware of the shortcoming shortcomings of the USSR's political system, Nehru believed in ending vested interest in land and instituting a new cooperative order based on socialistic ideals as the only solution to the eradication of poverty, unemployment, human degradation, and the prevailing imbalance in wealth.

Gandhi's walks through the villages of rural India endeared him with a profound love of the land and respect for the people who toiled in it. He came to believe that it was impractical for India's cities to accommodate the burgeoning population in a dignified way. He romanticized village life as self-sufficient, simple, free, non-violent, and truthful. To Gandhi, the qualities of village and rural life far surpassed that of the city, but he recognized that the playing field had to be leveled with both landscapes providing opportunities for personal growth and lifelong learning.

In a letter to Nehru, Gandhi admits that his proposed ideal village only existed in his imagination. His description of the village and its lifestyle can be interpreted as an ideal and harmonious community, or as an autonomous neighborhood.

The four characteristics embodied in Gandhi's idealized village would be: 1) access to an ever-expanding scientific and technical base in two areas, individual healthcare and assistance in food production; 2) respect and codes of conduct in human actions and toward natural resources; 3) a democratic political institutional framework; and 4) physical and electronic linkages between the village and both rural and urban areas.

Other ideal village goals which Gandhi intimated were the inclusion and provision for the full population range in demographics, a desire to diminish the divide in access to educational as well as economic opportunity, and a job-led economy rather than a capital intensive one.

I would speculate that Gandhi was in fact describing a community or neighborhood, which was reinforced in a later statement that he made to "put the village back into the city." He seemed to lament the difficulty of instilling the dignity of village life into the anonymity of the city.

My research leads me to dispute the notion that Nehru and Gandhi had differing visions for the future of India. Their visions were not mutually exclusive but rather they each chose to emphasize the two parallel futures of India, the city and the agrarian landscape.

In summary, Nehru wished to eradicate poverty through industrialization and urban commerce, whereas Gandhi idealized diverse self-governing communities in both the rural and urban landscapes. A robust community life is essential in the rural village as it is in any urban neighborhood, the building block of a successful city.

Dhiru Thadani is a practicing architect, urban designer, educator, and author of The Language of Towns & Cities: A Visual Dictionary. He is the recipient of the 2011 Seaside Prize, and has worked in North and Central America, Europe, and Asia.

Planetizen Federal Action Tracker

A weekly monitor of how Trump’s orders and actions are impacting planners and planning in America.

Map: Where Senate Republicans Want to Sell Your Public Lands

For public land advocates, the Senate Republicans’ proposal to sell millions of acres of public land in the West is “the biggest fight of their careers.”

Restaurant Patios Were a Pandemic Win — Why Were They so Hard to Keep?

Social distancing requirements and changes in travel patterns prompted cities to pilot new uses for street and sidewalk space. Then it got complicated.

Platform Pilsner: Vancouver Transit Agency Releases... a Beer?

TransLink will receive a portion of every sale of the four-pack.

Toronto Weighs Cheaper Transit, Parking Hikes for Major Events

Special event rates would take effect during large festivals, sports games and concerts to ‘discourage driving, manage congestion and free up space for transit.”

Berlin to Consider Car-Free Zone Larger Than Manhattan

The area bound by the 22-mile Ringbahn would still allow 12 uses of a private automobile per year per person, and several other exemptions.

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.

Heyer Gruel & Associates PA

JM Goldson LLC

Custer County Colorado

City of Camden Redevelopment Agency

City of Astoria

Transportation Research & Education Center (TREC) at Portland State University

Camden Redevelopment Agency

City of Claremont

Municipality of Princeton (NJ)