Planetizen talks with Peter J. Park, Manager of Community Planning and Development for the City of Denver, Colorado, about the return of physical planning, the city's form-based code, and more.

Portland gets a lot of press, but Denver, Colorado has been pushing the envelope of innovative urban planning for years now. With an expanding public transit system that is the largest in the country, Denver planners are tackling a lot of new station-area planning for transit-oriented development -- and they've only just finished adopting a brand-new form-based code. Denver's historic Union Station is being updated to be the central hub of the transit system, and an expansion is in the works for the busy Denver International Airport.

Steering all of this planning is Peter J. Park, Denver's Manager of Community Planning and Development. In conversation with Planetizen, Park eloquently addressed his beliefs about the field of planning and the return to a focus on physical form:

PARK: I think that planning as a profession started some hundred years ago with a strong emphasis on physical planning. At that time, landscape architects and planners and architects and engineers had very common foundations in understanding the design of cities. And then the evolution of the profession of planning, as in many professions, evolved into specialties, and oftentimes some of those specialties lost the connection with the physicalities of their policies.

I think the demand for design quality is unfortunately pretty low in a lot of places. I don't know if there's a low demand for design quality or there's a high level of acceptance for mediocre-to-bad design. Because when you present people with a better design for a street or a park or a building, when you put images together, most people will choose the better one. They're just willing to accept the lesser. So for me this issue of policy and design of the physical outcome is something that has been very important in my career, and it's actually been a place that I've been able to fortunately shape and align my interests with great job opportunities that I've had. I think that's where our role as planners in cities is going.

As planners we're constantly balancing the ideals of the planner, the views of the profession and values that you hold personally, with those of the community. We have the opportunity to influence the community's point of view. And then again, if planners educate the public, then they help to raise the bar of expectation in a community. Now, how does that begin then to translate to policies? If you talk about if from the point of view of "This is what planners think," well I think that can be very dangerous. There are plenty of folks, from developers to other community types, who don't share that point of view. And so I think, as planners, we have to take a more humble and patient approach to what we put out there to help people make informed decisions. And if they choose something that we wouldn't necessarily choose, then you know what? The community has spoken. We know that we did our best job of laying out the alternatives and I guess that is really what this community is. But in my experience, if we do a good job of showing alternatives and looking at implications of what the alternatives are, people choose well.

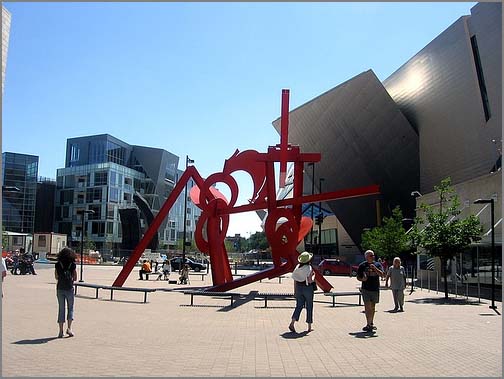

The new Denver Art Museum, with new condos in the background.

PLANETIZEN: How has the process gone of implementing a form-based code in Denver?

PARK: Denver's first zoning code was done in the 1920s, and it was updated in the 50s. In the mid-50s, the philosophy in most American cities was really one of starting over. It didn't value the city that existed at the time. Now, a lot of people might not know this, but Denver has very urban, deep roots. It is very urban in terms of street blocks, we had over 300 miles of streetcar lines and urban trains by the late 30s, so this was a very urban place. The zoning code in the 1950s really reversed that. For the last 50 years the city has been struggling with that code, and for the last 20 years now the city plans and comprehensive plan have called for rewriting the zoning code. We just finished it, it took us over 5 years to do it.

But what the code does is it takes a context-based and a form-based approach. By context, it distinguishes between the suburban parts of the city and the more urban parts of the city and downtown – pretty much the way that transect-based zoning works. And so these various attributes of the street block structure, the building forms, and how the building relate to their site and to each other, is reflected in the different contexts. The form-based aspect deals primarily with the form of the building, and again, their relationship to the site and to other buildings. And, more importantly, the relationship of the building in forming the public realm. So, for example, we have main street zoned districts. And in main street zoned districts the buildings are required to have a certain percentage at the build-to line – then you have a mass forming the street edge. Then you have a transparency and ground story activation requirement for entrances. For a main street that makes sense – for a strip mall that's not as important in a suburban context. So, the code distinguishes between these different physical contexts and then at a street block scale or neighborhood scale, and then also the regulations are calibrated for the building scale based on those contexts.

So that fixes that code from the 50s, which really was cumbersome and complicated and unreliable. In these economic times, we're looking for development that's going to contribute to the economy, that's going to contribute to the making of the city. And we have a continually growing place; people are still coming to Denver and the region. We talk about fixing the zoning code as a significant economic development initiative because that uncertainty goes away. We've rezoned a lot of properties to align with the policies and adopted plans, and now developers don't have to spend a lot of money on getting their properties rezoned and wondering what they can do with their land. The city has already spoken; it has already said, 'here is what we want on Main Street.' In many places we actually upzoned a lot of those places where we'd like to have higher density development. And, so if that's what you're going to do, come and get your permits. It's not a long, drawn out public process.

PLANETIZEN: You've been very involved with the New Urbanists, and worked under John Norquist in Milwaukee when he was mayor. Where do you fall in the debate between the 'traditional' architects and contemporary architecture?

PARK: Traditional, contemporary I really don't believe in architecture of time. I'm really more for timeless architecture. And so I'm not so much into historical replication. However, if you're going to do that, do it well. Because there's nothing worse than attempted replication. I think imitation may be the greatest form of flattery, but cheap imitation doesn't get you there. It's an insult.

But, in terms of the design side and the regulatory realm, you need to make sure that in your regulations you don't make it difficult for the good results to happen. That was one of the problems in our old code, it was hard to do good work. If I want to build a new building on an old main street, I have to set it back more than the 1920s streetwalk. Simple things like that.

Secondly, you need to strive to promote the best kind of design possible by putting images out there, talking about it, and building constituencies that would fit the demand or expectation of a higher quality product.

In situations where the city has some involvement in a project, whether it's part of an urban renewal, or whether it's the city selling land to someone who is going to do the development, those are the other opportunities where we can say, "We're partnering with you on this, and so we see this as an opportunity to set the mold for what could happen."

In other places that I've worked, for example in Milwaukee, the typical approach was that you'd seek out a master developer for any inner city redevelopment. Well, when I worked for John Norquist we took a different approach, and I searched out small sites that we could encourage developers to get interested in. And the idea was to have a lot of small things going on, with a high emphasis on design, so you get a lot of activity and a lot of different "products" (as they say in the real estate development world) with an emphasis on design quality. I mean, from the buyer point of view, if I can buy something and pay the same amount for a really beautifully crafted and well-designed building, why wouldn't I do that if it's in the right neighborhood? And so we managed to encourage a changing market demand and a lot of new, smaller architecture firms started cropping up as well as smaller developers. And now consumers having a lot more choices.

And you know, I think it has changed the market in Milwaukee. If you go to Milwaukee today you'll see the expectation in the design, the competency and demand for better design on the commercial scale and the residential scale has gone up. And it's because we got people talking about the importance of design from a consumer's point of view instead of creating more laws and more rules.

END

Planetizen Federal Action Tracker

A weekly monitor of how Trump’s orders and actions are impacting planners and planning in America.

Map: Where Senate Republicans Want to Sell Your Public Lands

For public land advocates, the Senate Republicans’ proposal to sell millions of acres of public land in the West is “the biggest fight of their careers.”

Restaurant Patios Were a Pandemic Win — Why Were They so Hard to Keep?

Social distancing requirements and changes in travel patterns prompted cities to pilot new uses for street and sidewalk space. Then it got complicated.

Platform Pilsner: Vancouver Transit Agency Releases... a Beer?

TransLink will receive a portion of every sale of the four-pack.

Toronto Weighs Cheaper Transit, Parking Hikes for Major Events

Special event rates would take effect during large festivals, sports games and concerts to ‘discourage driving, manage congestion and free up space for transit.”

Berlin to Consider Car-Free Zone Larger Than Manhattan

The area bound by the 22-mile Ringbahn would still allow 12 uses of a private automobile per year per person, and several other exemptions.

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.

Heyer Gruel & Associates PA

JM Goldson LLC

Custer County Colorado

City of Camden Redevelopment Agency

City of Astoria

Transportation Research & Education Center (TREC) at Portland State University

Camden Redevelopment Agency

City of Claremont

Municipality of Princeton (NJ)