Not until this month did a bus pass ever make its way into my wallet.

For two years I walked to work. Before that, gas cost a penny and a few hummed bars of "Livin' La Vida Loca" and climate change meant turning up the A/C. In the mid-2000s my commute got longer and I decided to take the bus. But not until this month did a bus pass ever make its way into my wallet.

So far, I've found that it confers a remarkable sort of freedom. It's not just the freedom not to pay. It's the freedom to go wherever you want without even having to think. The momentary caculus of whether it's worth the $1.50 to go across town to pick up a baguette or see The Love Guru does not even have to cross your mind. Transfers, exact change, and all the rest go by the wayside as well.

It's especially nice here in San Francisco, where the city is small enough and the buses frequent enough that you can pretty much walk out your door, step off the curb and find yourself headed in roughly the right direction. It's kind of like an open-air elevator.

Naturally, I wish this sort of freedom and ease on everyone. Not just because I'm altrusitic but because bus-riding incurs all-too-rare positive externalities. When more people ride the bus, that means fewer idiots on the road, which, in turn, makes the bus' drive quicker. It also puts more money in the farebox, which presumably leads to even shorter headways and better overall service.

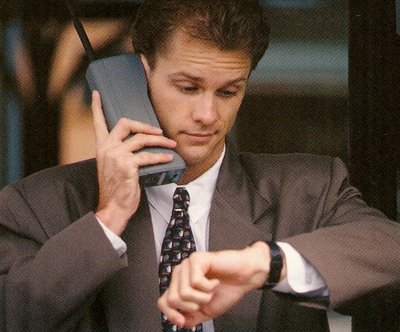

Transit agencies, however, still struggle with attracting discretionary bus riders and with getting them to commit to something as pedestrian (no pun intended) as a monthly pass, which in some circles would be like carrying an NRA membership card. And I'm not talking about riders forced on by high gas prices; they're no longer discretionary. But no matter how expensive gas gets, there are still people who could easily take the bus but refuse to do so out of snobbery, habit, or ignorance. Indeed, though trains seem to be doing OK, buses are, stereotypically, not stuff that white people like. If I was a fancy consultant I'd try to figure out how to bill transit agencies $500 an hour to reel in those riders. I'm not a fancy consultant, but those externalities and my own half-baked excitment are enough for me to propse a few marketing strategies that the nation's transit agencies should consider. They might not be able to make the bus cool, but they can make it more appealing and, perhaps,

Transit agencies, however, still struggle with attracting discretionary bus riders and with getting them to commit to something as pedestrian (no pun intended) as a monthly pass, which in some circles would be like carrying an NRA membership card. And I'm not talking about riders forced on by high gas prices; they're no longer discretionary. But no matter how expensive gas gets, there are still people who could easily take the bus but refuse to do so out of snobbery, habit, or ignorance. Indeed, though trains seem to be doing OK, buses are, stereotypically, not stuff that white people like. If I was a fancy consultant I'd try to figure out how to bill transit agencies $500 an hour to reel in those riders. I'm not a fancy consultant, but those externalities and my own half-baked excitment are enough for me to propse a few marketing strategies that the nation's transit agencies should consider. They might not be able to make the bus cool, but they can make it more appealing and, perhaps, more economical.

more economical.

I am operating under the premise that a large transit agency attracts several hundred thousand unique customers today and that it has a captive audience for a least a little while. Ads inside buses are old news and on-bus video is obnoxious, but far more opportunities remain with which agencies can snare the elusive yuppie and companies can creatively hawk their wares.

Coffee: Companies love targeting their promotions not merely to demographic groups but, even more fervently, to activity groups. If you're trying to sell a product, what a customer does matters more than who he or she is. So who better to sell coffee to than a bunch of blearly-eyed early morning commuters? I'm not saying that Starbucks should set up kiosks on buses; that would be a disaster. But how about a coupon for everyone who boards? They could be dispensed with the kind of ticket machines that grocery stores use with little fuss.

The extra bonus of a Starbucks or other socially acceptable coffee company is that the bus service will draw cachet from it. Starbucks enhances the transit agencies image--making it acceptable for upscale customers--while giving Starbucks access to ideal customers (who are likely to drink coffee anyway). (And if you object to corporations, then a network of indepedent coffee houses could do the very same thing.)

Newspapers: You remember newspapers. Those messy grey things upon which democracy depends? There's a strong correlation between the length of a typical bus ride and the time it takes to read the morning paper. Newspaper companies are desperate for readers, and newspapers don't spill -- so how about some vending racks right behind the yellow line?

The Interweb: The product that cannot be cross-marketed on the internet has yet to be invented, and the possibilities for transit agencies are endless. I'm sure that their websites get many hundreds of thousands of hits per day, and each visit is a chance for advertisers to place tasteful ads and for all manner of contests and cross promotions. (Among others, San Francisco's BART already does this, with contests and featured destinatoins and so forth.)

Monthly Passes as Discount Cards: If they work for student travelers, why not daily travelers? Monthly passes could double as coupons at selected quality retailers, thus generating revenue for the transit agency and making the passes more valuable for users.

Direct Mail Trip Planning: This one is more elaborate, but in order to combat complacency that stems simply from not knowing where to go or how to ride the bus, transit agencies should send direct mailings citywide with instructions and invitations for users to log on, devise a route to work, and then enter some kind of PIN or code that would confer a prize or coupon (iTunes download, Girls Gone Wild site membership, Planning Report subscription, or whatever). That way, the user would have incentive to visit the site, and he would end up with a trip all mapped out -- and no more excuses.

iPhone: Every day for the past three days my flatmate has returned home with tales of yet more things his new iPhone G3, replete with GPS and a brain of its own, can do. If transit companies cannot harness the power of this device, well, then we'd all better just start walking.

The list could go on. Any of these schemes requires, of course, marketing staff on both ends -- advertiser and transit agency -- savvy enough to come up with creative schemes and mutaually beneficial partnerships. Indeed, running a bus company doesn't have to involve only timetables and maintaince schedules. It must also cultivate positive images and as many collateral benefits as possible -- whether riders are captive or discretionary.

Just to be clear, I'm not in favor of wholesale commercialization or of making every moment of the human experience a chance to launch a promotion. But some things, like bus riding, are inherently bleak experiences, often marked by resignation and discomfort. For what it's worth, commerce can connect bus riding to the world at large. It can add value, make it more famliar, and create incentives that are not quite so threatening as $5 per gallon gas.

Planetizen Federal Action Tracker

A weekly monitor of how Trump’s orders and actions are impacting planners and planning in America.

Map: Where Senate Republicans Want to Sell Your Public Lands

For public land advocates, the Senate Republicans’ proposal to sell millions of acres of public land in the West is “the biggest fight of their careers.”

Restaurant Patios Were a Pandemic Win — Why Were They so Hard to Keep?

Social distancing requirements and changes in travel patterns prompted cities to pilot new uses for street and sidewalk space. Then it got complicated.

Platform Pilsner: Vancouver Transit Agency Releases... a Beer?

TransLink will receive a portion of every sale of the four-pack.

Toronto Weighs Cheaper Transit, Parking Hikes for Major Events

Special event rates would take effect during large festivals, sports games and concerts to ‘discourage driving, manage congestion and free up space for transit.”

Berlin to Consider Car-Free Zone Larger Than Manhattan

The area bound by the 22-mile Ringbahn would still allow 12 uses of a private automobile per year per person, and several other exemptions.

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.

Heyer Gruel & Associates PA

JM Goldson LLC

Custer County Colorado

City of Camden Redevelopment Agency

City of Astoria

Transportation Research & Education Center (TREC) at Portland State University

Camden Redevelopment Agency

City of Claremont

Municipality of Princeton (NJ)