Lee D. Einsweiler, principal and co-founder of Code Studio, offers practiced insight on the relationship between planning and implementation, as well as guidance for a fulfilling career navigating the two.

Lee D. Einsweiler graduated with a master's degree in regional planning from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill before eventually co-founding a planning consultant firm that is currently working with cities like Detroit, Cleveland, and Los Angeles to implement innovative new zoning code systems.

In this interview, published originally in the 6th Edition of the Planetizen Guide to Graduate Urban Planning Programs, Einsweiller discusses a career as a leading consultant in the world of zoning codes, working on some of the most ambitious zoning reform projects in the United States.

How do you describe your work, and how does it fit into the broader field of planning?

How do you describe your work, and how does it fit into the broader field of planning?

I am a principal and co-founder of Code Studio, a firm focused on planning, urban design, and plan implementation. Our strongest role is when we work in planning and then implement those plans, especially for zoning and subdivision regulations.

What is the difference between long-term planning and implementation?

There are a lot of plans sitting on shelves across the country. Nothing ever happened for those plans; nothing became functional. That’s the worst outcome for planning. Implementation should be a foundational element of the preparation of a plan. But in many cases, the plan leaves implementation for future thinkers to prepare. When plans lack an eye toward implementation, they will inevitably fail. The planning process needs to include the first steps of implementation.

What projects are you working on that include implementation in the planning process?

The largest project that we are working on right now is the zoning code project for the city of Los Angeles. The zoning code for Los Angeles is fascinating because it's modular, meaning it can be applied to community plans around the city in a variety of ways. Planners will have the implementing tools they need no matter where they are working in a very large city. New community plans will create the zoning maps—putting the zoning on the ground—but the tools that come together to build the district and apply development standards, like parking and landscaping, will all have been pre-prepared as a variety of options. The combination of those pieces creates the rules for how development can occur.created

The zoning code therefore requires planning. It’s not just as simple as saying, "I want a residential district." If you want a residential district that allows a variety of building types, or if you want to allow more than one family to live in a house, all of those questions can be answered by the new modular code.

We have also just begun to work in Detroit, which is at the absolute opposite end of the planning and development spectrum compared to Los Angeles.

In Detroit, there is very little development activity, so there is very little implementation. The challenge there is to remove barriers and open opportunities for development. A lot more planning is unnecessary.

Detroit is building a lot of new buildings in the downtown area. But in the rest of the city, people are re-inhabiting existing buildings. The old view of zoning ordinances as a tool for separating uses is breaking down. The old view needs to break down in Detroit, so people can reuse the old buildings. What’s needed is action, not planning.

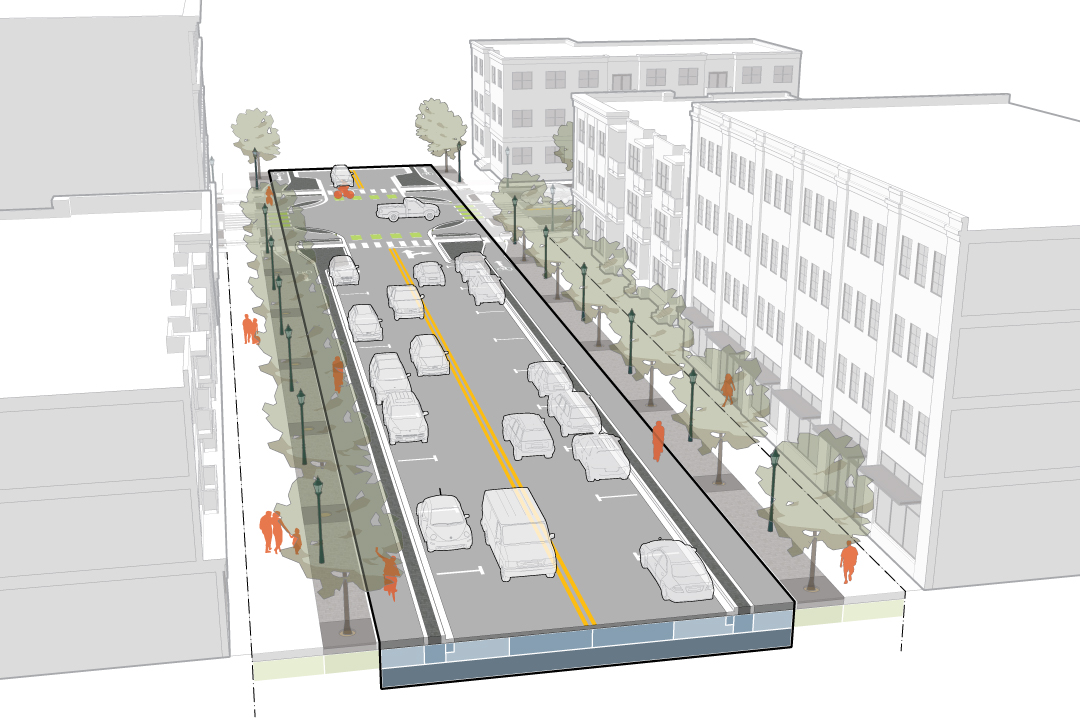

Rendering for visualization of the re:code LA project, a comprehensive overhaul of the zoning code for the city of Los Angeles. (Image courtesy of Code Studio)

Given the wide spectrum of planning approaches that you’ve just described, how would you describe the current era of planning?

The planning industry, and certainly the zoning industry, is responding to two tremendous challenges.

The first is improving urban design in cities and communities. The era of cheap construction of boxes on the landscape, fronted by large, suburban-style parking lots, is fading fast. We are finally seeing the value of density, and we are realizing that low-density development cannot be supported in the long run. Urban design sensibilities can yield good urban places.

The second is the question of equity. Equity rears its head in a variety of ways in zoning. One is the simple challenge of the barriers that use-based zoning has put in place for many, many years. One of the most significant of those barriers is the idea that the single-family home is sacrosanct, and it should seldom, if ever, mix with other housing types. Traditional development patterns have all of those housing types—apartments, townhouses, more than one unit on a single property. All of those disappeared in the post-1950s rush to the perfect single-family suburban home. Now as a challenge of equity, we are forced to rethink those ideas. In high-value single-family neighborhoods, it’s difficult to have that conversation because a home is the most valuable investment that homeowners have made in their life. Anything that suggests a threat to that value is scary. Since that value took a hit in the recession, that’s still fairly fresh in people’s memories.

The same equity question expands beyond questions about single-family homes, like with elements like the availability of alcohol. Cities make it very difficult to locate things like a micro-brew pub. Even though people want a restaurant on the corner to be able to sell a glass of wine, sometimes it’s really, really hard to do that. The opening of gyms, the opening of doggie day cares—all kinds of things have created challenges for the traditional styles of zoning. Traditional zoning has not been responsive to the locational desires of people. People want those uses close by, but zoning says they belong only in very particular areas.

There is a tradition of planning in your family. How do you make sense of the history of planning that you’re talking about now that it’s your chance to change the direction of the field?

The basic strengths of urban versus suburban and rural elements of planning have always been a part of the conversation. My grandfather was a small-town mayor. He was involved with historic preservation, and his town is one of the most beautiful, historically preserved river towns in Illinois, and will be well into the future. He did his job right.

My dad was a famous land use planner, trained as an architect. He understood the issues we are grappling with today. The issue he was grappling with in his work was large-scale growth management—the kind of growth that showed up on a regional or statewide basis. He came out of the Minneapolis-St. Paul Metropolitan Council, where he was the director of research. He was also involved in the management of the development challenges of the day and was not shy about implementation.

Unfortunately, not everyone in the industry operated that way. People in planning don’t all have the same beliefs about the importance of urban design and equity. Now there are entities like Strong Towns pointing out the challenges of continuing urban sprawl, but we still aren’t paying attention to the numbers or figuring out how to solve those challenges. We’re not paying attention to the facts because certain segments of the industry are thrilled to provide what the marketplace will buy. Sprawl is like shopping at a big box store—it’s cheap, but it’s not a long-term benefit to your community. Single-family housing is the same way. We don’t account for the long-term costs of providing a place for single-family homes, whether it’s the roads, the sewers, or the costs of the home.

What kind of choices would you recommend potential graduate students make so they end up on the right path in their career?

There are probably two different ways to enter the field, which was made clear to me as a student at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. One way is to focus broadly on how to think about policy challenges, and the other is to dive deeply into a narrow skill set. We were told, again and again, that we were being trained for ten years into our careers. The program actually refused to provide certain kinds of classes considered too much about technology. We would probably have to understand those concepts at some level, and they could probably provide a good job right out of school, but they might turn out to be a dead end.

The example I’m thinking of right now is GIS mapping. If you become an expert in geographic information system (GIS) mapping, you’ll get a job right out of school, instantly, without a doubt. There is a lot of need for mapping in a variety of settings. That skillset will get you a job, but you find yourself in that job for a while, with few opportunities to advance. Once you’ve designed and built beautiful maps, there isn’t a lot left to do.

I was trained with a little more time spent on the fundamentals of planning thinking and theory. Those concepts can be applied well into the future. I am confident that what I do now for a living is something that my professors would have been thrilled to discover.

One of the traps people fall into is not thinking about their whole career. In that longer career, either you will have multiple careers or you will have a single trajectory. You have to make a decision about whether you’re going to a planning institution that focuses more heavily on policy and policy thinking, or whether you are going to a tools and techniques institution.

What kind of students are you hoping will enter the professional field of planning?

I hope they are diverse in racial and gender representation. It continues to be difficult to find diverse planners to work on a variety of projects. I hope the schools can find a way to help us all increase the diversity of the field.

Useful backgrounds for moving successfully into planning include geography and political science. Geography is slightly more practical. My business partner and I both come from a geography background. Political science is helpful for creating the real policy wonks that we all need at the top of the policy pyramid and are sorely needed all across the country right now, especially in the federal government. Political science graduates bring long-term and deep policy thinking as an advantage to the table.

Recently, we have been employing undergraduate architects or urban designers who have gone on to advanced degrees in planning. They understand not just the building and the site of the building, but larger questions about the city and the building’s role in the block or the neighborhood.

[Disclosure: Code Studio partners with Planetizen's parent company, Urban Insight, on the re:code LA project, and the author of this post has worked with Code Studio professionally in the past.]

Planetizen Federal Action Tracker

A weekly monitor of how Trump’s orders and actions are impacting planners and planning in America.

Maui's Vacation Rental Debate Turns Ugly

Verbal attacks, misinformation campaigns and fistfights plague a high-stakes debate to convert thousands of vacation rentals into long-term housing.

Restaurant Patios Were a Pandemic Win — Why Were They so Hard to Keep?

Social distancing requirements and changes in travel patterns prompted cities to pilot new uses for street and sidewalk space. Then it got complicated.

In California Battle of Housing vs. Environment, Housing Just Won

A new state law significantly limits the power of CEQA, an environmental review law that served as a powerful tool for blocking new development.

Boulder Eliminates Parking Minimums Citywide

Officials estimate the cost of building a single underground parking space at up to $100,000.

Orange County, Florida Adopts Largest US “Sprawl Repair” Code

The ‘Orange Code’ seeks to rectify decades of sprawl-inducing, car-oriented development.

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.

Heyer Gruel & Associates PA

JM Goldson LLC

Custer County Colorado

City of Camden Redevelopment Agency

City of Astoria

Transportation Research & Education Center (TREC) at Portland State University

Jefferson Parish Government

Camden Redevelopment Agency

City of Claremont