Planopedia

Clear, accessible definitions for common urban planning terms.

What Is CEQA?

Designed to assess the environmental impacts of new projects and provide mitigation measures, the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) has a controversial history, sometimes serving as a convenient tool for groups intent on stopping or slowing development.

As freeways proliferated and urban development boomed in the 1960s, environmental advocates around the country fought to pass regulations to protect biodiversity, prevent pollution, and incorporate environmental impact into planning and development. By 1972, the federal government had passed the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), the Clean Air Act, and the Clean Water Act, which all established regulatory systems for protecting the nation's air quality, water, and other environmental assets.

Passed in 1970 and signed into law by then-Governor Reagan, the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) is a state law designed to ensure that proposed projects such as housing developments, road construction, transit projects, and other types of development provide to the public an assessment of their projected environmental impacts and, if needed, a set of actions to mitigate any significant impacts and protect California's ecosystems and natural resources. Other states soon followed suit, with 15 more states passing their own environmental review laws between 1971 and 1991. State laws vary in their applications. While all 16 states require environmental review for state actions and projects, only five require review for local projects, three require it for private projects, and two (California and Massachusetts) have updated their policies to reflect climate change concerns.

CEQA has four major goals: to inform decision makers and the public about the potential impacts of development; prevent significant, avoidable damage; identify mitigation strategies; and disclose how and why decisions about the projects were made. The law requires agencies and developers to evaluate the possible impacts of proposed projects and implement mitigation strategies where needed.

Initial CEQA studies are undertaken by the state, city, or county agency with jurisdiction over the proposed project. An initial study will yield one of three outcomes: a Negative Declaration, Mitigated Negative Declaration, or Environmental Impact Report (EIR). If the initial study triggers a full EIR, the agency or project contractor must conduct the full study before proceeding with the project.

There are some exemptions to CEQA analysis, including categorical exemptions (project classes deemed to not have significant impacts) such as: repairs or additions to existing facilities or landscaping, subdivision of residential buildings, conversion of buildings to certain new uses, minor alterations to land, and other specific activities deemed unlikely to have significant effects on the environment. The state legislature can also choose to exempt particular projects by statute.

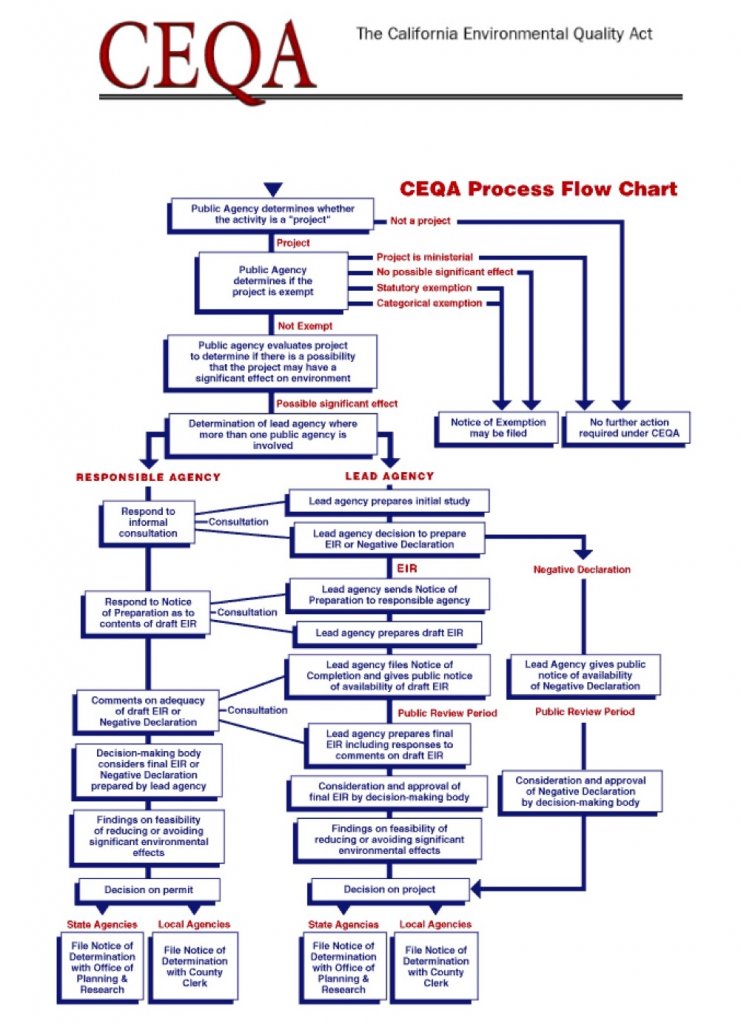

The flow chart below illustrates the CEQA process.

State of California Resources Agency

Criticism and controversy

Since its inception, CEQA has drawn criticism from a variety of opponents. One one hand, pro-development and housing advocates say that CEQA creates unnecessary hurdles to development and raises the cost of construction, adding to the state's housing crisis and sometimes killing affordable housing projects altogether. Some housing developers and density advocates believe the law makes it too difficult and expensive to build high-density projects that ultimately reduce their residents' carbon footprints and create more affordable housing. CEQA opponents are often labeled as 'NIMBYs' resistant to change and insensitive to the urgent need for increased housing production.

On the other hand, environmentalists and environmental justice activists argue the law doesn't go far enough to protect natural resources and public health. Advocates for strengthening CEQA say that too many projects get approved despite inadequate mitigations. For example, some projects are allowed to raze a wooded area in exchange for replanting felled trees in another area. However, this practice can fragment wildlife habitat and disturb existing ecosystems. Environmental justice groups claim that industrial projects often get the go-ahead despite having significant negative impacts on the long-term health of the surrounding community.

Meanwhile, data show that a majority of CEQA lawsuits target publicly funded, environmentally-minded projects like public transit and renewable energy. According to one study, transit projects are challenged more than roadways, while renewable energy projects face the most resistance of any industrial or utility projects. Infill development projects, those in existing communities that take advantage of previously developed space and existing infrastructure, are the "overwhelming target" of CEQA lawsuits. In the private sector, high-density housing projects have met the most pushback via CEQA lawsuits.

Yet for all the controversy, surprisingly few projects that fall under CEQA review actually face litigation. According to a study from the Rose Foundation for Communities and the Environment, less than 1 percent of the 54,000 projects reviewed under CEQA between 2013 and 2015 faced litigation. According to a report from The Housing Workshop, "many complex factors," including restrictive local zoning, interest rates, and high labor and materials costs, contribute to California's housing crisis, but CEQA is not a major factor.

In early 2022, CEQA once again burst into the public consciousness as California's Supreme Court ruled in favor of a neighborhood group that sued the University of California, Berkeley over its plan to expand admissions and build additional student housing. The Berkeley case might signal a turning point, with state lawmakers decrying the court's decision as a blow to the state's commitment to provide quality education and housing for students. The California legislature swiftly reversed the court's decision by passing a law that exempts state colleges and universities from some CEQA requirements.