Transportation affordability is important but often misunderstood, resulting in misguided solutions. New research helps identify ways to provide true affordability for economic freedom, opportunity and happiness.

Transportation affordability is an important but often misunderstood planning issue. Although per-mile travel costs are lower in North Americans now than most other times and places, households spend more on transportation in total, resulting in stress, unhappiness and conflict.

My new report, Evaluating Transportation Affordability, provides detailed analysis of transportation cost burdens and practical ways to reduce them. This research indicates that common assumptions about transportation affordability are wrong, and many proposed solutions are misguided, they actually make the problems worse.

Let me share key insights.

Affordability is important

Transportation unaffordability is a major problem for many people. High transportation costs reduce people's ability to access services and activities (shops, healthcare, education and jobs), force lower-income travellers to use inferior modes (unsafe sidewalks, dangerous bicycling conditions, crowded and dirty public transit, etc.) and causes many households to overspend on travel expenses. When families cannot afford healthy food, healthcare or education, the ultimate reason is often excessive transportation costs that leave insufficient money for other necessities.

Half of all hard-luck stories begin with a vehicle failure, crash, or traffic citation that leads to some combination of unemployment, poverty, disability, and legal problems. Studies show that households located in automobile-dependent areas have higher housing foreclosure rates – an indicator of financial crisis – than residents of more multimodal communities where travellers have more affordable accessibility options, indicating that affordable transportation increases economic resilience; and households' ability to overcome financial shocks.

High costs of living cause many people to lead lives of quiet desperation: they work more than they want at jobs they dislike to spend more than they can afford on vehicles they need to commute to those unpleasant jobs. Unaffordability forces people to prioritize income over other life goals such as devoting their time to art, travel, learning, or caring for loved ones. Described more positively, increasing transportation affordability helps improve happiness, freedom, opportunity, resilience and political popularity.

What do we want? Affordability!

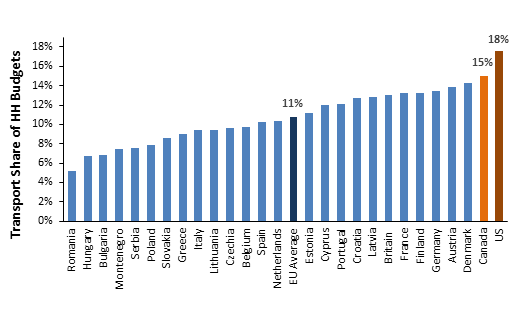

Affordability refers to the costs of goods relative to incomes, and households’ ability to purchase necessities such as food, housing and healthcare. Transportation affordability refers to households’ ability to purchase the travel needed to access goods and activities within their budget limits. Experts recommend devoting no more than 15% of household budgets to transportation or no more than 45% to housing and transport combined; most North American households spend more than these limits, far more than in peer countries, as illustrated below.

Household Transportation Expenditures by Country

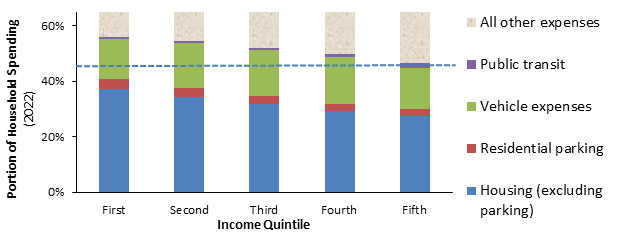

The following figures show the portion of household spending devoted to housing and transportation (H+T) by income quintile (fifth of all households). Most households spend more than 45 percent, indicated by the dashed line, which is more than is considered affordable.

H+T Expenditures by All Households

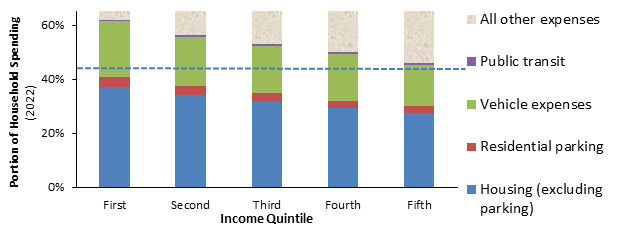

These cost burdens are particularly high for low-income vehicle-owning households, which typically spend more than 20 percent of their budgets on transportation and more than 60 percent on H+T combined, as illustrated below.

H+T Expenditures by Vehicle-Owning Households

Although these graphs indicate that housing costs affect affordability much more than transportation costs, that is not entirely true. For one thing, a portion of housing costs are actually vehicle costs, including residential parking and property taxes devoted to roadways, so multimodal planning increases housing as well as transportation affordability. In addition, transportation costs are much more variable than housing costs, making them more burdensome. For example, a motorist might only spend $4,000 on their vehicle most years, but occasionally twice that amount due to major mechanical failures, crashes or traffic citations, leading to a financial crisis.

Misconceptions

There are many misconceptions about unaffordability problems and potential solutions.

The first is that automobile transportation can become affordable if governments minimize user costs such as fuel taxes, road tolls, parking fees, and insurance premiums. It cannot.

Automobile travel incurs many costs so reducing individual costs provide only modest savings. For example, fuel represents about 20 percent of total vehicle expenses and in the U.S. taxes represent about 20 percent of fuel costs, so cutting fuel taxes in half would only reduce total fuel expenses by 2 percent and total vehicle costs by less than one percent. This indicates that many commonly proposed affordability strategies are token, they only provide small savings. To be substantial, affordability strategies must reduce a major portion of vehicle expenses including purchase, financing, insurance, and residential parking costs.

It is important to account for all costs when evaluating affordability. Households often make trade-offs between housing and transportation costs. For example, parking mandates make driving cheaper but increase housing costs. A cheap house is not truly affordable if located in an isolated area where transportation costs are high, and households can rationally spend more for a house located in an accessible, multimodal neighborhood where transportation costs can be minimized.

True affordability requires resource savings not just economic transfers. Underpricing vehicle expenses simply shift costs to other sectors which reduces affordability overall. For example, low fuel taxes and road tolls increase general taxes (to pay roadway costs not funded by user fees). “Free” parking increases housing costs (for residential parking) and the price of goods (for customer parking). No-fault insurance reduces crash victim compensation.

Another common mistake is to ignore the additional economic costs of policies that reduce non-auto travel options. Underpricing automobile travel increases driving and creates automobile-dependent communities where it is difficult to get around by affordable modes. This increases traffic problems and associated costs, and reduces travel options for non-drivers. In such communities, non-drivers frequently require chauffeuring, which increases drivers' time and money cost burdens.

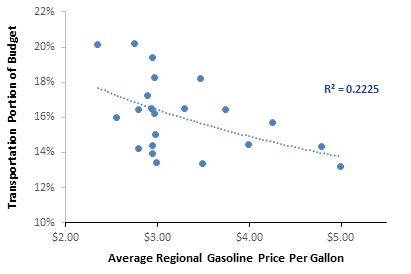

These effects are demonstrated by the following graph which shows that the portion of household spending devoted to transportation declines with higher fuel prices, the opposite of what most people assume. Why? The small savings in fuel costs are more than offset by the total additional costs of increased automobile ownership and use. In addition, automobile-dependency and sprawl increase non-monetary costs including time spent traveling, crash disabilities and health problems caused by sedentary living.

Transportation Spending Versus Fuel Price

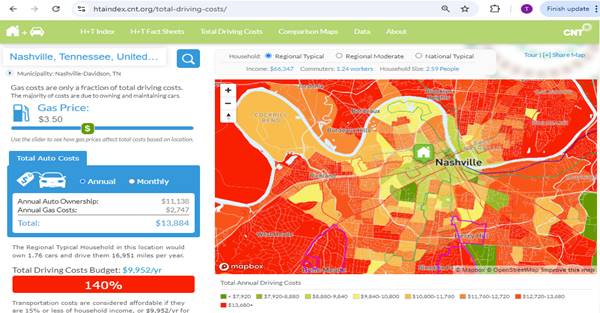

Automobile-based affordability solutions reflect mobility-based planning, which assumes that our goal is to maximize travel speed and distance by making driving cheaper. True affordability requires accessibility-based planning which strives to minimize the distances people must travel to reach services and activities, which reduces total transportation costs. This is illustrated by H+T Affordability Index maps, such as the following, which show that households in accessible, central neighborhoods spend far less on transportation than those at the urban fringe.

Housing and Transportation (H+T) Affordability Index

Another misconception is that targeted policies such as social housing, subsidized cars or fare-free transit will provide affordable transportation. Individually such policies only address a small portion of needs. For example, a million-dollar housing subsidy budget can typically provide about four single-family homes with garages, ten multifamily homes with off-street parking, and twenty multifamily homes with unbundled parking. Even a free car can be unaffordable to lower-income households due to high insurance, fuel and repair costs. Free transit can only serve a minor portion of trips. True affordability requires an adequate number of affordable homes located in multimodal neighborhoods where residents can minimize their transportation costs.

Strategies for true affordability

My research indicates that true transportation affordability results from public policies that favor affordable modes and compact development over expensive modes and sprawl. Of course, some households are willing to bear the additional costs of automobile travel, but many would choose more affordable alternatives if available. True affordability serves those unmet demands.

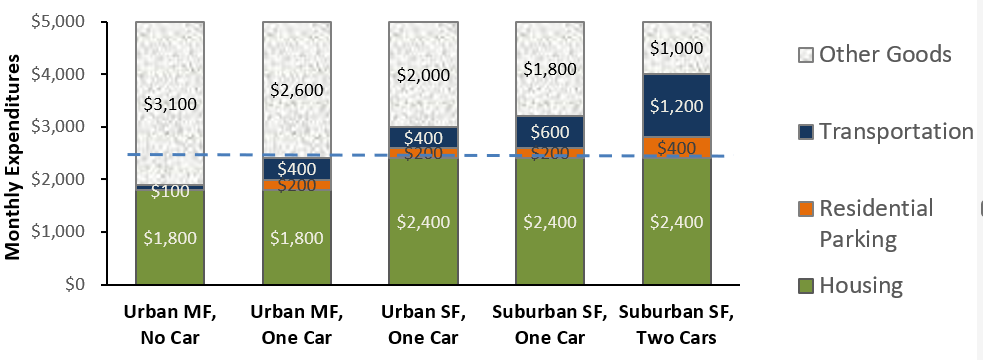

The figure below illustrates the potential savings from true affordability planning. It shows typical housing and transportation costs for an average income household with a $5,000 monthly budget, The most affordable option is multifamily (MF) housing with unbundled parking located in a multimodal neighborhood where residents can minimize vehicle ownership and use. Single family (SF) suburban housing tends to have significantly higher housing and transportation costs.

Housing and Transportation (H+T) Costs

The grey area labeled "Other Goods" indicates the amount of money remaining after households pay housing and transportation expenses. For a typical household, basic multifamily housing located in a multimodal neighborhood where it is easy to live car-free leaves more than three thousand dollars to spend on other goods, providing a great deal of financial freedom. Owning just one low-annual-mileage car increases housing and transportation expenses to 45% of the household budget, which is considered the limit for affordability. For a typical household, single-family housing and owning multiple cars is usually unaffordable, leaving insufficient money to spend on other goods. Of course, actual costs vary depending on specific family needs and conditions, but the basic relationships are consistent: compact housing located in multimodal neighborhoods is generally the most affordable overall.

Do a thought experiment: if your community had an abundance of one- and two-bedroom apartments that rent for $600 to $1,500 per month (plus $200 per month for each parking space used), located in friendly, walkable neighborhoods, would some households choose those affordable options over single-family homes in automobile-dependent areas? I believe that many would, and as a result would be freer, happier, and more successful.

Affordability requires policies that ensure that any household that wants can find such housing. Cities that encourage basic apartment development, such as Montreal, typically have 20-40 percent lower housing costs than cities that restrict multifamily development and mandate off-street parking, and households located in compact, multimodal neighborhoods typically spend 40-60 percent less on transportation than in automobile-dependent areas.

Below is a list of policies to create such communities.

Multimodal Affordable Transportation Policies

-

Apply a sustainable transportation hierarchy in planning and funding. Align individual planning decisions to support strategic goals.

-

Improve and encourage affordable modes including walking, bicycling, e-bikes, public transit, car-sharing and telework.

-

Spend at least the portion of infrastructure budgets on affordable modes as their potential mode shares. For example, if walking and bicycling improvements would result in 20% active mode shares, they should receive up to that portion of funding for fairness sake, or more to achieve strategic goals and make up for past underinvestments.

-

In economic evaluations give extra weight to improvements to affordable modes and benefits to lower-income travellers.

-

Support vehicle sharing (carsharing and MaaS) and encourage households to right-size their vehicle fleets.

-

Implement Smart Growth policies that create compact, multimodal neighborhoods where it is easy to use affordable modes.

-

Increase affordable housing in multimodal neighborhoods.

-

Apply complete streets policies to ensure that all streets accommodate affordable modes.

-

Reform parking policies to increase efficiency. Unbundle and cash out free parking so non-drivers are no longer forced to subsidize parking facilities they do not need.

-

Implement TDM incentives that encourage travellers to use affordable and resource-efficient modes when possible.

A new paradigm

Despite its importance, transportation planners currently give little consideration to affordability. Few transportation agencies have specific affordability goals or ways to evaluate progress toward them. Many common planning practices prioritize speed over affordability, which favors faster but more expensive modes over slower but lower-cost alternatives and sprawl over compact development.

This creates a cycle of increased automobile dependency and sprawl which ratchets up the travel needed to access services and activities, and therefore the money that people must spend to achieve a given level of accessibility. When measured by effective speeds (travel distances divided by time spent traveling plus time spent earning money to pay travel expenses), lower-wage workers are worse off.

Conventional economics ignores this. It assumes that money leads to happiness, so our goal is to maximize productivity and income so we can purchase more goods. However, many other factors affect happiness, and wealth introduces new costs and risks that can offset happiness gains. A better approach strives to maximize the amount of happiness provided per unit of income, resource consumption and travel: more delight per dollar, more gladness per gallon of fuel, and more smiles per mile of travel.

Note that this approach conflicts with standard political ideologies. Ideological conservatives advocate economic growth in order to increase all households' incomes. Ideological liberals advocate economic transfers that increase lower-income households' incomes and subsidies. Both perspectives assume that the goal is to allow households to purchase more mobility and larger homes. Affordability planning requires a new perspective that strives for sufficiency and efficiency, and so favors affordable and resources efficient modes and housing.

Affordability planning is challenging. Politicians want to implement policies that seem quick and visible, even if they are ineffective and wasteful, and will avoid policies that seem to impose new costs. Many base their priorities on ideology rather than research. The results are often ineffective and wasteful.

How to be poor but happy

By conventional economic metrics, North Americans can be considered successful; we have greater productivity, higher incomes, and cheaper goods than most other times and places. Yet, many people feel economically stressed and discontent, and North Americans fare poorly by many quality of life outcomes such as longevity, economic mobility (the chance that as adults children earn higher incomes than their parents), and the amount of time they devote to socializing and leisure. Why?

This research indicates that many common policies favor expensive transportation and housing over lower-cost alternatives, which drives the cost of living beyond what is affordable, leaving too little money to purchase other necessities. The result is immiseration: growing stress, unhappiness, and discontent.

The solution is simple: planning should favor affordable over expensive modes and compact development over sprawl. This is not to suggest that automobile travel is bad and should be eliminated. Many people are justifiably proud of being able to afford a nice car, and automobiles are the most efficient option for some trips. However, automobile travel requires far more resources and is far more expensive than other modes, typically by an order of magnitude, so true affordability requires an efficient, multimodal transportation system that allows travelers to choose the options that truly reflect their needs and preferences.

Affordability requires a new economic paradigm; rather than trying to increase incomes or subsidies we need to increase affordability and efficiency so households can satisfy their basic needs consuming fewer resources and spending less money. Our planning should be guided by a new goal: how can we help families be poor but happy.

Planetizen Federal Action Tracker

A weekly monitor of how Trump’s orders and actions are impacting planners and planning in America.

Chicago’s Ghost Rails

Just beneath the surface of the modern city lie the remnants of its expansive early 20th-century streetcar system.

Amtrak Cutting Jobs, Funding to High-Speed Rail

The agency plans to cut 10 percent of its workforce and has confirmed it will not fund new high-speed rail projects.

Ohio Forces Data Centers to Prepay for Power

Utilities are calling on states to hold data center operators responsible for new energy demands to prevent leaving consumers on the hook for their bills.

MARTA CEO Steps Down Amid Citizenship Concerns

MARTA’s board announced Thursday that its chief, who is from Canada, is resigning due to questions about his immigration status.

Silicon Valley ‘Bike Superhighway’ Awarded $14M State Grant

A Caltrans grant brings the 10-mile Central Bikeway project connecting Santa Clara and East San Jose closer to fruition.

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.

Caltrans

City of Fort Worth

Mpact (founded as Rail~Volution)

City of Camden Redevelopment Agency

City of Astoria

City of Portland

City of Laramie