There is no war on cars. Everybody, including motorists, benefit from a more diverse and efficient transportation system. Let there be peace!

Some people complain that new multi-modal planning practices, such as bike- and bus-lanes, traffic speed reductions and new parking fees, are a "war on cars." Much of their evidence is ridiculous, some of which has already been refuted on the Planetizen website.

Framing this as a "war" implies that motorists are victims of violent assaults. Should motorists really fear ferocious pedestrians, berserk bicyclists, and armed buses? Of course not. Their complaints are unfounded, like the grousing of drunks at a late night bar, but their claims have been widely circulated on the internet and published in newspapers, and if left unchallenged may discourage efforts to make our transportation system more diverse, efficient and equitable.

Complaints about a "war on cars" demonstrate that automobiles make people selfish. The majority of transportation investments and road space are devoted to automobile travel, yet motorists are not satisfied, they want even more.

Claims that motorists are under attack are particularly cruel because pedestrians and bicyclists really do face violence from motor vehicle traffic. Much of what motorists call a “war on cars” consists of efforts to increase the safety, convenience and comfort of other travel modes. Let’s examine in detail, and in some cases laugh, at claims of a “war on cars.”

A War on Cars? Let There Be Peace!

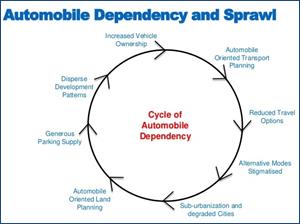

Let’s be clear: there is no war on cars. During the last century, transportation planning was automobile-oriented: the majority of planning resources (money, road space, and design priorities) were devoted to improving automobile travel, often to the detriment of other travel modes. Wider roads and higher traffic speeds create barriers to walking and bicycling, increase risks to all road users, and minimum parking requirements subsidize car travel and encourage sprawled development, creating sprawled communities where it is difficult to reach destinations without a car. The result is automobile dependency and sprawl (see figure below), which increases economic, social and environmental costs.

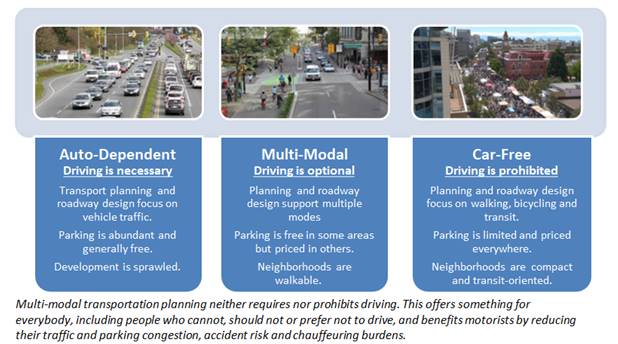

In response, many communities are starting to implement more multi-modal transportation planning that improves travel options, encourages more efficient travel, and creates more compact communities. However, this is no more a “war on cars” than a healthy diet is a “war on food.” Multi-modal planning allows travellers to choose the most efficient mode for each trip: walking and bicycling for local trips, public transit on busy urban corridors, and driving when it is truly optimal, considering all impacts. Multi-modal transportation planning neither requires nor prohibits driving. It is a middle way between Automobile-Dependent and Car-Free transportation planning (see below). Motorists benefit from multi-modal planning that reduces their traffic and parking congestion, the risk of being the victim of other drivers’ errors, and chauffeuring burdens.

Auto-Dependent, Multi-Modal, and Car-Free Planning

Some motorists argue that driving is more important than other travel modes. They say things like, "You can’t deliver furniture by bicycle" or "I shouldn’t be forced to walk ten miles to work." This misses the point: each mode has a role to play in an efficient and equitable transport system. It would be inefficient to deliver heavy freight by bicycle or walk ten miles to work, but it is also inefficient if parents must drive children to school due to a lack of sidewalks or crosswalks, or if people who want to bicycle commute cannot do so due to unsafe riding conditions.

Multi-modal planning requires motorists to share roads with other modes, drive slower and pay for parking in some areas, but does not prevent people from driving when and where they want. Even ambitious goals, such as California [pdf] targets to reduce vehicle travel 15%, cars will continue to be the most common travel option.

Why Here? Why Now?

Current demographic and economic trends justify more multi-modal planning:

- An aging population [pdf] is increasing the number of adults who cannot or should not drive, and so require other travel options.

- Changing consumer preferences. Surveys indicate that many people want to drive less and living in a walkable urban neighborhood. Multi-modal planning responds to these preferences.

- Affordability and social justice. Housing and transportation are most household’s two largest household spending categories; multi-modal planning increases affordable travel options and reduces parking costs that must be incorporated into rents and mortgages. It also ensures that people who cannot, should not, or prefer not to drive for some trips receive a fair share of public resources.

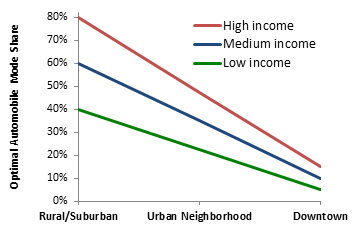

- Increasing urbanization. Urban land is scarce and valuable, and expanding urban roads and parking facilities is costly. As a result, Improving and encouraging use of space-efficient modes is often the most cost effective and beneficial solution to urban traffic problems. The figure below illustrates the optimal auto mode shares in various locations.

In affluent, sprawled rural areas and suburbs, most trips can be by automobile, but this should decline with density, particularly in neighborhoods where many households cannot afford cars or many residents have mobility impairments. More multi-modal planning creates communities where it is easy to get around without a car.

- Increasing health and environmental concerns. Multi-modal planning allows people to walk and bicycle for fitness and health, and reduces per capita pollution emissions and pavement area.

- Local economic development. Multi-modal transportation helps support economic development by increasing affordability and community livability and supporting local industries.

Do People Walk and Bicycle? Do We Spend Too Much on Non-Auto Modes?

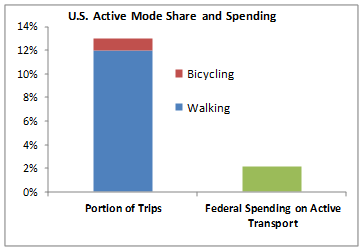

Critics sometimes claim that few people walk, bicycle or use public transit, so investing in these modes is wasteful and unfair. Let’s look at some numbers.

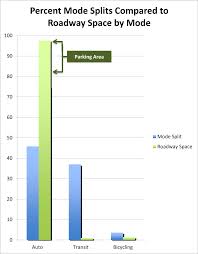

According to the 2017 National Household Travel Survey about 11% of personal trips are by walking and 1% bicycling, with higher rates during peak periods and in central cities where traffic problems are greatest. Yet, only about 2.1% of federal transportation funding is devoted to these modes, according to the "Bicycling & Walking Benchmarking Report," as illustrated below.

Similarly, bicycling and public transit receive less than their fair share of road space. In San Francisco [pdf], 37% of trips are by transit, but only 1.2% of road space is dedicated to bus lanes, and 4% of trips are by bicycle, but only 1.5% of road space is dedicated to bike lanes.

There are several reasons to increase public transit investments, beyond its mode share. Public transit [pdf] plays two different and often conflicting roles in an efficient and equitable transportation system: resource-efficient mobility on dense urban corridors, and basic mobility for non-drivers. Although only about 2.8% of total personal trips are by public transit (bus, train and paratransit), plus 1.9% by school bus, its mode share is much higher in denser urban areas, and it is often cheaper overall than alternatives, such as expanding urban roads and parking facilities, and providing taxi services for non-drivers. High quality public transit provides a catalyst for more compact, multi-modal neighbohood development, which leverages additional savings and benefits. For these reasons, governments traditionally devote about 20% of their transport budget to public transit, and more in larger cities. This suggests that it would be efficient and fair to at least 12% of transport investments to active modes and 20% on public transit, and even more could be justified for the following reasons:

- To make up for past underinvestment. During the last century most communities invested little in non-auto modes, so additional investments are justified for several years to catch up.

- To serve latent demand. Consumer surveys indicate that many people want to drive less, rely more on other travel options, and live in more compact, walkable neighborhoods, provided they are convenient and affordable. Additional investments are justified to satisfy these demands.

- To efficiently solve traffic problems. Expanding roads and parking facilities is very costly. Improving alternative modes is often the most cost-efficient way to reduce traffic problems. Even people who always drive benefit from improvements to other modes that reduce congestion, accident risk, pollution and chauffeuring burdens.

Do Motorists Pay for Roads? Is it Unfair to Spend Tax Dollars on Pedestrians and Bicyclists?

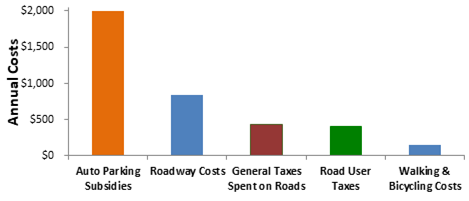

Some people consider it unfair to spend motorists’ road user fees to support other modes. However, road user fees do not actually cover all roadway costs. For example, in the U.S., fuel taxes and tolls provide only $111 (51%) of $219 billion total roadway spending. This averages 7¢ for each of the 3,100 billion vehicle-miles driven, about 3.5¢ funded by user fees and 3.5¢ funded by general taxes. Similarly, a major Transport Canada study, The Full Cost Investigation of Transportation in Canada [pdf], estimated that in 2000, provincial and municipal governments spent $35 billion on roadways (Table 6-3), which averages 12¢ for each of the 300 billion vehicle-kilometers driven [pdf], more than twice what motorists contribute in road user taxes and fees.

In addition, in a typical city there are 2-8 government-mandated off-street parking spaces per vehicle each with $500-3,000 annualized value, considering land, construction and operating costs. These costs incorporated into mortgages, rents and the price of other goods. Walking and bicycling have much lower facility costs, probably about 1¢ per mile, plus $50-300 per year for bicycle parking. Because motor vehicles require more costly infrastructure than other modes, and motorists travel more than other mode users, motorists impose far greater road and parking facility costs. Much of these costs are borne by general taxes, and incorporated into mortgages, rents and prices of other goods that people pay regardless of how they travel. As a result, people who drive less than average tend to overpay their share of infrastructure costs, subsidizing road and parking costs for their neighbors who drive a lot.

For example, a typical motorist who drives 12,000 annual miles and consumes 600 gallons of fuel, receives $2,000 in parking subsidies (parking costs not paid directly by users), and imposes about $840 in total roadway costs, but pays only about $400 annually road user taxes; their remaining facility costs are paid through general taxes and the prices of other goods. Somebody who walks and bikes 10 miles a day only imposes about $150 annually in facility costs.

Facility Costs and Tax Payments

A major portion of parking subsidies and roadway costs are paid by general taxes and incorporated into mortgages, rents and consumer good prices that residents pay regardless of how they travel. As a result, motorists tend to underpay and non-drivers tend to overpay their share of facility costs.

Do Bicycle Improvements Increase Bicycling and Traffic Safety?

Some people, including some experienced bicyclists, question whether protected bike paths increase ridership and safety. Protected bike lanes are intended to attract less experienced bicyclists. They are not ideal for all cyclists, particularly experienced bicyclists who want to ride fast. Numerous academic studies indicate that they generally do increase bicycle travel [pdf], and safety for all road users. One major study found that segregated bike paths are both safer and tend to increase cycling by travellers who want to bicycle but feel unsafe riding on roadways. A recent study published in the American Journal of Public Health, “Safer Cycling through Improved Infrastructure,” found that cities that invest most in protected bikeways achieve the largest increases in ridership and safety.

An extensive body of research [pdf] indicates that total traffic casualty rates, including risk to motorists, tend to decline as walking and bicycling mode share increases, an effect called “safety in numbers” [pdf]. Several factors probably contribute to these benefits: many strategies for improving pedestrian and bicycle safety, such as lower traffic speeds, also increase motor vehicle safety, and as walking and bicycling increase, driving declines, particularly by higher risk groups such as youths, seniors and people impairments, reducing motorists’ risk of being the victim of other drivers’ errors.

Do Bicycle Improvements Force People to Bicycle?

One senior argues, “the idea of being pressured into riding a bike again, against my wishes or physical capability, is akin to being encouraged to move back into a cave like our far-distant forefathers.” That is silly, nobody is forced to use bicycle facilities, and motorists benefit when other travellers shift to bicycling. Perhaps the best response was this letter by another senior, Gail Meston:. from an article titled "Ice cream and the ‘War’ on Cars":

I am delighted with the city’s determination to create viable transportation alternatives, including the network of separated bike lanes that make it safe to ride downtown. Recent letter writers creaming Victoria city council for just that, might want to chew on this: When new flavours of ice cream were introduced, it wasn’t deemed to be a “war” on chocolate. It was simply about providing new and exciting alternatives to those inclined to venture beyond familiar tastes and habits. As alternative flavours became increasingly popular, smart vendors added the new items to their confectionary menus. It was good for business and the bottom line to add a variety of choices.Chocolate hasn’t disappeared. It remains popular and is still widely available for committed chocolate lovers. Who knows — as word spreads about how yummy some of the new flavours are, even some of the chocolaters may be tempted to try a taste of something new. It seems like a win-win-win situation to me. Those who insist that because they love driving so much, everyone else must drive too, may want to check out the local ice cream shop!

Aren't Bicycles Zero Emission Vehicles?

Vehicle fuels have large external costs, so many jurisdictions offer thousands of dollars in subsidies to purchase “zero emission” electric vehicles. However, this is a misnomer: because electricity generation produces pollution they should be called “elsewhere emitting vehicles.”

In addition to purchase subsidies, electric vehicles also avoid most road user taxes; together these subsidies total several hundred or even a few thousand dollars a year for each electric vehicle. Walking and bicycling are true zero emission modes but receive no comparable subsidy. Because shoes and bikes are inexpensive, they don’t need subsidies, instead, we want walking and bicycling facility improvements. The FHWA's Nonmotorized Transportation Pilot Program invested about $100 per capita in pedestrian and cycling improvements in four typical communities, which caused walking trips to increase 23% and cycling trips to increase 48%, mostly for utilitarian purposes, plus increased recreational and exercise activity, providing many benefits (traffic and parking congestion reductions, consumer savings, increased safety and health, and more independent mobility for non-drivers) in addition to emission reductions, such programs receive a fraction of the subsidy provided to electric vehicles.

Should Governments Mandate Housing for Cars But Not People?

No law mandates that communities provide housing for people, but most jurisdictions governments require property owners to provide abundant, expensive, and generally free housing for cars, typically totalling 2-8 parking spaces with thousands of dollars in total annualized value per motor vehicle. Parking is never really free, the choice is really between paying parking costs directly, through user fees, or indirectly, through mortgages, rents and taxes which people pay regardless of how they travel. This significantly reduces affordability. For example, one study of 23 recently completed Seattle-area multifamily housing developments revealed that parking regulations increase rents approximately $250 per month, or 15% total although that approximately 20% of occupants own no motor vehicles, and during peak periods 37% of parking spaces are unoccupied.

Every time somebody purchases a car they expect governments to force other people to pay for its parking. This is perverse: they force poorer car-free households to subsidize the parking costs of affluent motorists, and increases and traffic problems. Parking mandates are a fertility drug for cars. Why do they exist? Because motorists demand these subsidies and efforts to change these practices are criticized as a “war on cars.”

Is Multi-modal Planning “Social Engineering”? Does it Reduce Freedom?

Some critics claim that regulations, such as fuel economy standards, and transportation management programs that encourage efficient travel, reduce people’s personal freedom and opportunity. These are distorted and incomplete claims. According to Washington State Transportation Center director Mark Hallenbeck, “All transportation planning is social engineering. We've spent 100 years making it easy to drive. We've spent 100 years making it really hard to [walk, bicycle or] take a bus. So people drive, because it makes sense.”

Automobile-oriented transport planning increases some freedoms but reduces others: it reduces urban motorists’ ability to drive fast and park for free, but increases freedom to travel by other modes, which tends to increase financial freedom, and increases freedom from traffic risks and pollution impacts, and from government-mandated parking subsidies.

Multi-modal Planning Impacts on Personal Freedom

Reduces Freedom and Opportunity |

Increases Freedom and Opportunity |

|

|

Multi-modal planning reduces some freedoms but increases others.

Surveys indicate that many people want to drive less and rely more on other mode, provided they are convenient, comfortable and affordable. For example, the National Association of Realtor's National Community Preference Survey found that most respondents like walking (80%), about half like bicycling, more than a third (38%) like public transit, and nearly 60% report being forced to drive due to inadequate alternatives. Younger people are much more likely to prefer walkable neighborhoods, bicycling, and transit, suggesting that demand for these modes will increase. To the degree that multi-modal planning responds to these demands it is not “social engineering.”

Much of the opposition to multi-modal planning reflects a general reluctance to change. Some people are so accustomed to driving that they cannot imagine taking the bus when travelling downtown, or walking and bicycling for local errands. However, after people try new transport options they often find them appropriate and useful, and their opposition declines.

It's Only Fair, Motorists Should Pay Their Share

Most parking is subsidized, so plans to expand when and where parking is prices are often criticized as unfair to motorists and part of "war on cars." But there are good reasons to charge for parking: it is fairer than subsidizing parking facilities and helps reduce traffic problems. There is a specific reason that municipal governments should charge for parking: that helps ensure that out-of-town motorists pay their share of local roadway costs. In most central cities, a major portion of motorists are not residents and so do not pay property taxes that fund local infrastructure. You could argue that out-of-town visitors pay these costs indirectly by supporting local businesses, but a major portion of central city customers and workers travel without a car and so have much lower infrastructure costs. Charging for parking collects extra money from motorists to help offset the extra roadway costs they impose. It's only fair.

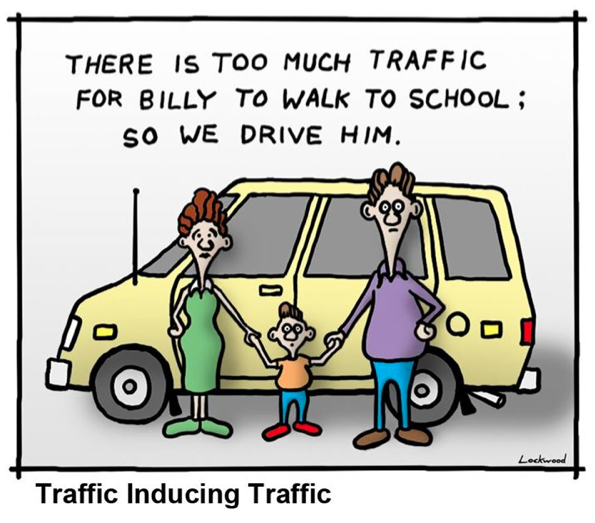

Is There a Shortage of Children’s Feet? Should Children Be Free-range?

Automobile-dependent planning deprives young people of independence. Two generations ago most children walked or biked to school, but now most are driven in cars. Why? Is there a shortage of children’s feet? No, these changes result from planning that favors driving over active modes, which creates a self-fulfilling prophecy: as more parents drive their children to school, walking and bicycling become more difficult, dangerous and stigmatized. Ultimately, everybody is worse off. Children’s physical, mental and social development requires independent travel: they should be “free range.” What do they need to do this? Better walking, bicycling and public transit, of course! Criticizing multi-modal planning as a “war on cars” deprives future generations of health, freedom and happiness.

Should Governments Continue to Encourage Drunk Driving and Sprawl?

A guy walks into a bar and buys a drink. Another guy drives to the bar and also buys a drink. About 50¢ of the cost of each drink goes to finance the bar’s parking. As a result, the guy who walks subsidizes the drivers’ parking of the guy who drives, thanks to local zoning laws.

This is foolish! We tell people not to drink and drive, but at the same time governments mandate that restaurants, pubs and bars provide abundant parking that encourages driving. This is particularly harmful because those parking requirements often prevent the development of neighborhood restaurants and bars that customers could reach by walking: an old storefront or house might make a terrific restaurant or pub, but cannot meet parking requirements. Why do these foolish laws exist? Because motorists insist! Whenever reduced and more flexible parking requirements are proposed, motorists complain that they will be inconvenienced, and criticize reforms as part of the “war on cars.”

Mixed Messages

It is understandable that many people are confused and frustrated. On one hand, we are inundated with commercial advertising and social messages trying to convince us that owning a suitable car will make us happy and successful. On the other hand, many jurisdictions have plans and programs to reduce automobile travel; people fear that they will lose happiness and success. Similarly, responsible and sensitive motorists may resent the implication that their travel behavior is "bad" and should be reduced. In response they are likely to claim that they are a "better than average driver," and describe some irresponsible behavior by pedestrians and bicyclists. However, that misrepresents the issue: driving is not bad, it is expensive: it requires far more space for travel and parking, imposes more road wear, risk and pollution, and increases user costs and stress. Motorists need to realize that even if they observe traffic rules and keep their vehicles properly maintained, their driving still imposes significant external costs, including congestion, parking subsidies, accident risk and pollution damages, so everybody benefits if automobile travel is used sparingly. A multi-modal transportation system tends to maximize affordability, happiness and productivity by allowing travellers to choose the best mode for each trip.

Many young men devote their time and money to buying a car because they believe that it will improve their chances of dating a popular partner. However, smart singles realize that they are actually better off dating car-free guys, who will have more money to spend on their dates, and he’ll look better in shorts, since driving makes people fat and lazy.

Are Signal Controls Really Set to Delay Traffic?

One critic claims, without evidence, that traffic engineers intentionally adjust signals set to delay traffic. He should have talked with a traffic engineer first. Although it is sometimes possible to give traffic a continuous “green wave” on one road in one direction, this is impossible to achieve on all urban roads. For example, signals can be optimized into downtown during the morning and out of downtown during the afternoon, on north-south streets, but that will conflict with traffic optimization on east-west streets. In addition, signals must accommodate bus priority, pedestrians, and emergency vehicles.

Stop blaming traffic engineers for congestion problems! If you want to know the real culprit, look in the mirror. Every time you drive during rush hour, you contribute to congestion. Shifting just 10-20% of peak-period car trips to other times, modes or destinations would significantly reduce traffic problems.

Are Complete Streets Policies Unfair? Will They Backfire?

Roads are most municipal government’s most valuable asset. It is important that they are designed and managed to serve all residents, including the needs of non-drivers. Complete streets policies ensure that public roads accommodate diverse users and uses, including walking, bicycling, transit, driving, sitting and parking, plus local residents and businesses. Motorists sometimes criticize these programs as a “war on cars,” because they reassign road space from automobiles to other modes and they reduce traffic speeds. However, these changes tend to benefit all road users overall, including motorists, by improving travel options and reducing total crash risks.

Critics sometimes threaten that such programs will backfire because bike- and bus lanes, traffic calming, and more walking and bicycling will increase pollution due to more idling, cause accidents due to driver frustration, or discourage local visitors and business activity. However, abundant research indicates that multi-modal planning and complete streets make communities overall safer [pdf], healthier [pdf], more affordable [pdf] and inclusive, less polluting [pdf], and economically successful [pdf], because any negative impacts are more than offset by shifts from driving to efficient modes and more attractive streets.

Are Most Bicyclists Irresponsible Scofflaws?

Some critics argue that bicyclists do not deserve facilities or safety programs because of their irresponsible behaviors, citing examples of bicyclists who violate traffic law or ride without proper lighting or helmets. “They must earn their right to use public roads,” they argue.

But all types of road users violate traffic laws. Field surveys find that bicyclists and motorists violate traffic laws at similar rates, but in different ways. Motorists frequently exceed posted speed limits, avoid paying required parking fees, fail to wear seatbelts, and text while driving. Researcher Wesley Marshall found that many bicyclists violated traffic laws in ways intended to increase their safety, such as riding on sidewalks, passing on the right while vehicles are stopped at a traffic signal, and failing to make a full stop at stop signs and red lights in order to maintain momentum and balance. A Florida study found 88% law compliance rates by bicyclists, slightly higher than the 85% compliance rate for drivers.

Automobiles Contribute to Modern Plagues and Deadly Sins

Previous generations suffered from plagues caused by deprivation: too little food, poor sanitation, exhausting labor, infectious diseases, and dangerous working conditions. Those plagues are now uncommon, but have been replaced with new ones, many resulting from excess automobile travel.

Old Plagues |

New Plagues |

|

|

Plagues of poverty have been replaced by those of affluence, mostly caused by excessive automobile travel.

Good research indicates that these problems tend to increase with per capita automobile travel and declines with improved walkability, multimodal transportation, and more compact development:

- Improved walkability is associated with reduced foreclosure rates and neighborhood crime.

- More multimodal transport is associated with improved public health and income equality.

- More compact development is associated with reduced traffic deaths, improved economic opportunity, and improved national economic productivity.

This makes sense because automobile travel is expensive and imposes high infrastructure and accident costs. More multimodal transportation saves resources and improves opportunities to physically and economically disadvantaged people.

What Is the Real War on Cars?

There is now a real war on cars, a "worldwide fight to undo a century’s worth of damage wrought by the automobile" with its own YouTube Channel and Podcasts. However, this is a war of hearts and words, rather than violent attacks against motorists. It has enlisted diverse allies including The Economist, and even Car and Driver Magazine, which recently recognized that, "Maybe its [the city's multi-modal] policies will cut down on congestion and provide a boon to those who actually like to drive."

Conclusions

Most communities are automobile dependent, making it difficult to get around without a car. This is no accident; for the last century, transportation planning emphasized automobile-oriented infrastructure design and investments to the detriment of other modes. This ultimately harms everyone, including motorists who face increased congestion, crash risk and chauffeuring burdens. As a result, smart communities are starting to implement more multi-modal planning, with more investments in walking, bicycling and public transit, complete streets roadway designs, and reduced parking subsidies. That creates a more efficient and equitable transportation system in which travellers can choose the most appropriate mode for each trip, and people who cannot, should not, or prefer not to drive receive their fair share of public resources.

Some people only see problems and overlook the benefits of these changes. They claim there is a “war on cars,” which is inaccurate, unfair and dangerous. Many of their complaints are wrong or exaggerated, and by claiming to be victims of a “war,” they contribute to conflict and violence. How should we respond? With facts and humor.

For More Information

Hamed Ahangari, Carol Atkinson-Palombo and Norman Garrick (2017), “Automobile Dependency as a Barrier to Vision Zero: Evidence from the States in the USA,” Accident Analysis and Prevention, Vol. 107, pp. 77-85.

Marlon G. Boarnet (2013), “The Declining Role of the Automobile and the Re-Emergence of Place in Urban Transportation: The Past will be Prologue,” Regional Science Policy & Practice, Special Issue: The New Urban World – Opportunity Meets Challenge, Vol. 5/2, June, pp. 237–253 (DOI: 10.1111/rsp3.12007).

Jeffrey Brinkmanand and Jeffrey Lin (2019), Freeway Revolts!, Working Paper 19-29, Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia.

Charlemagne (2019), "Streets Ahead Europe is Edging Towards Making Post-car Cities a Reality," The Economist.

Scott Cohen and Stefan Gössling (2015), "A Darker Side Of Hypermobility," Environment and Planning A, Vol. 47, pp. 1661-1679.

Tony Dutzik, Gideon Weissman and Phineas Baxandall (2015), Who Pays for Roads? How the “Users Pay” Myth Gets in the Way of Solving America’s Transportation Problems, CALPIRG.

Chad Frederick (2017), America's Addiction to Automobiles: Why Cities Need to Kick the Habit and How, ABC-Clio.

Stefan Gössling, Marcel Schröder, Philipp Späth and Tim Freytag (2016), “Urban Space Distribution and Sustainable Transport,” Transport Reviews.

Daniel Herriges (2019), "Evolution, Not Revolution" in Curbing Car Dependency, Strong Towns.

Peter L. Jacobsen, F. Racioppi and H. Rutter (2009), “Who Owns the Roads? How Motorised Traffic Discourages Walking and Bicycling,” Injury Prevention, Vol. 15, Issue 6, pp. 369-373.

Todd Litman (various years), The Selfish Automobile, Mythbusting: Exposing Half-Truths That Support Automobile Dependency, and More Bicycle Route Debate, Or Valuing Multi-Modalism, Planetizen.

Todd Litman (2015), Whose Roads? Evaluating Bicyclists’ and Pedestrians’ Right to Use Public Roadways, Victoria Transport Policy Institute.

Planetizen "War On Cars" Page.

Jeff Sabatini (2018), The War on Cars Is Real, and It's Being Led by Cities, Car and Driver Magazine.

Bob Shanteau (2013), The Marginalization of Bicyclists, I Am Traffic (www.iamtraffic.org).

Gregory H. Shill (2019), “Americans Shouldn’t Have to Drive, but the Law Insists on It; The Automobile Took Over Because the Legal System Helped Squeeze out the Alternatives,” The Atlantic.

The War on Cars podcasts about the epic, hundred years’ war between The Car and The City.

Planetizen Federal Action Tracker

A weekly monitor of how Trump’s orders and actions are impacting planners and planning in America.

Chicago’s Ghost Rails

Just beneath the surface of the modern city lie the remnants of its expansive early 20th-century streetcar system.

San Antonio and Austin are Fusing Into one Massive Megaregion

The region spanning the two central Texas cities is growing fast, posing challenges for local infrastructure and water supplies.

Since Zion's Shuttles Went Electric “The Smog is Gone”

Visitors to Zion National Park can enjoy the canyon via the nation’s first fully electric park shuttle system.

Trump Distributing DOT Safety Funds at 1/10 Rate of Biden

Funds for Safe Streets and other transportation safety and equity programs are being held up by administrative reviews and conflicts with the Trump administration’s priorities.

German Cities Subsidize Taxis for Women Amid Wave of Violence

Free or low-cost taxi rides can help women navigate cities more safely, but critics say the programs don't address the root causes of violence against women.

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.

planning NEXT

Appalachian Highlands Housing Partners

Mpact (founded as Rail~Volution)

City of Camden Redevelopment Agency

City of Astoria

City of Portland

City of Laramie