What amount of expansion, population and vehicle densities, housing mix, and transport policies should growing cities aspire to achieve? This column summarizes my recent research that explores these, and related, issues.

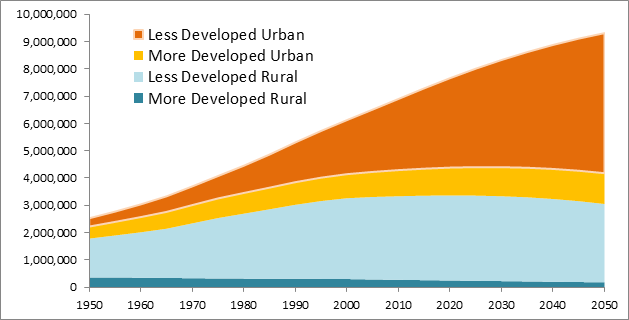

How should cities develop? This is an important and timely issue. We are currently in the middle of a major period of urbanization. According to United Nations projections, between 1950 and 2050 the human population will approximately quadruple and shift from 80 percent rural to nearly 80 percent urban. Although most of this growth is occurring in developing countries, developed country cities are also experiencing growth as more households choose urban over suburban neighborhoods. How cities develop has huge economic, social and environmental impacts. With proper policies we can leave a legacy of truly sustainable development for future generations.

World Urbanization (based on United Nations Projections)

The world is currently experiencing rapid urbanization, particularly in developing countries.

My new report, "Analysis of Public Policies that Unintentionally Encourage and Subsidize Sprawl," written in partnership with LSE (London School of Economics) Cities Program, for the New Climate Economy, provides practical guidance for creating cities that are healthy, wealthy and wise, that is, attractive and healthy places to live, economically successful, socially vibrant and equitable. It analyzes the costs and benefits of various development patterns and discusses ways to optimize urban expansion, densities, housing mix, and transportation policies for various types of cities. Let me summarize some of the report's key conclusions and recommendations, with the hope that it will inspire you to read the full document.

This study begins by defining sprawl and smart growth. These differ in many ways, as summarized in the following table.

Sprawl and Smart Growth

Sprawl |

Smart Growth |

|

|

Lower-density, dispersed activities. |

Higher-density, clustered activities. |

|

|

Land use mix |

Single use, segregated. |

Mixed. |

|

Growth pattern |

Urban periphery (greenfield) development. |

Infill (brownfield) development. |

|

Scale |

Large scale. Larger blocks and wide roads. Less detail, since people experience the landscape at a distance, as motorists. |

Human scale. Smaller blocks and roads. Attention to detail, since people experience the landscape up close. |

|

Services (shops, schools, parks, etc.) |

Regional, consolidated, larger. Requires automobile access. |

Local, distributed, smaller. Accommodates walking access. |

|

Transport |

Automobile-oriented. Poorly suited for walking, cycling and transit. |

Multi-modal. Supports walking, cycling and public transit. |

|

Connectivity |

Hierarchical road network with many unconnected roads and walkways. |

Highly connected roads, sidewalks and paths, allowing direct travel. |

|

Street design |

Streets designed to maximize motor vehicle traffic volume and speed. |

Reflects complete streets principles that accommodate diverse modes and activities. |

|

Planning process |

Unplanned, with little coordination between jurisdictions and stakeholders. |

Planned and coordinated between jurisdictions and stakeholders. |

|

Public space |

Emphasis on private realms (yards, shopping malls, gated communities, private clubs). |

Emphasis on public realms (shopping streets, parks, and other public facilities). |

Sprawl and smart growth vary in many ways.

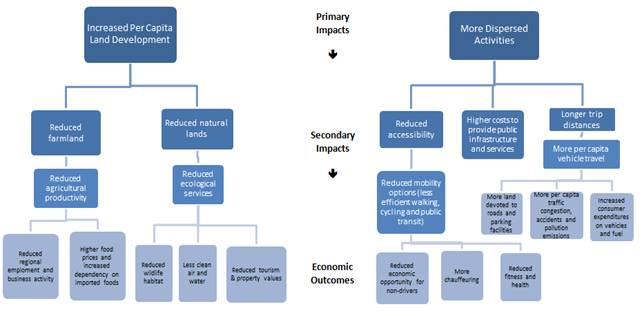

The study then compared the physical and economic effects of these two development patterns. There are two primary impacts to consider: sprawl increases per capita land consumption, which displaces other land uses, and it increases the distances between activities, which increases per capita infrastructure requirements and the distances service providers, people and businesses must travel to reach destinations. These primary impacts have various economic costs including reduced agricultural productivity, environmental degradation, increased costs of providing utilities and government services, reduced accessibility and economic opportunity for non-drivers, and increased transport costs including vehicle expenses, travel time, congestion delays, accidents and pollution emissions, as illustrated in the following figure.

Sprawl Resource Impacts

Sprawl has two primary impacts: it increases per capita land consumption, and by dispersing destinations it increases the costs of providing public infrastructure and services, and increases the distances that people must travel for a given level of accessibility, which increases total per capita transportation costs.

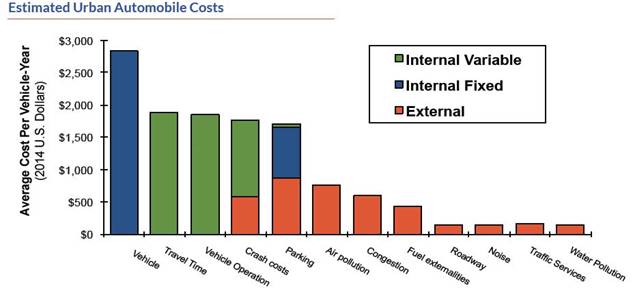

Previous studies have quantified and monetized (measured in monetary units) many of these impacts, but this study is the most comprehensive effort to date to integrate them all into one analysis framework. The study divided U.S. cities into quintiles (fifths), from smartest growth to most sprawled, and estimated the additional costs of more sprawled development. For example, the analysis indicates that by increasing the distances between homes, businesses, services, and jobs, sprawl raises the cost of providing infrastructure and public services by 10-40 percent. Using various sources of data about these costs, it calculates that the most sprawled quintile cities spend on average $750 annually per capita on public infrastructure, 50 percent more than the $500 in the smartest growth quintile cities. Similarly, sprawl typically increases per capita automobile ownership and use by 20-50 percent, and reduces walking, cycling, and public transit use by 40-80 percent, compared with smart growth communities. The increased automobile travel increases direct transportation costs to users, such as vehicle and fuel expenditures, and external costs, such as the costs of building and maintaining roads and parking facilities, congestion, accident risk, and pollution emissions. The following figure illustrates estimates of these costs.

Motor vehicle ownership and use imposes a variety of costs, including many that are external (imposed on other people).

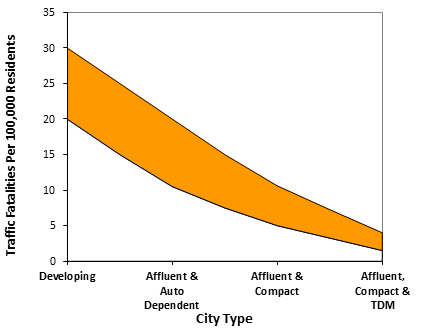

How cities develop significantly affects human safety and health. Smart growth reduces per capita vehicle travel and traffic speeds, resulting in far lower traffic casualty rates than in sprawled communities. By significantly increasing daily walking and cycling activity, smart growth also tends to increase public fitness and health, which reduces healthcare costs associated with physical inactivity and obesity.

Traffic Deaths Trends

Traffic fatalities per 100,000 residents typically average 20-30 in developing country cities, 10-20 in affluent, automobile-dependent cities, 5-10 in affluent, compact cities, and just 1.5-3 in affluent, compact cities with strong transportation demand management (TDM) programs.

Sprawl tends to harm physically and economically disadvantaged people by reducing the efficiency of affordable travel modes such as walking, cycling, and public transit. With sprawled development, more affluent households tend to move to isolated, automobile-dependent areas, leaving poverty concentrated in urban neighborhoods, which tends to exacerbate social problems such as crime and social exclusion. In contrast, research discussed in this report indicates that, all else being equity, crime rates tend to be lower in compact, mixed, multimodal neighborhoods due to increased passive surveillance (there are more "eyes on the street" to report potential threats) and improved economic opportunity for at-risk residents.

Extensive research also indicates that smart growth tends to increase economic productivity by improving accessibility which provides agglomeration efficiencies, reducing infrastructure and transportation costs, and reducing the need to import vehicle fuel. These factors are particularly important in cities in developing country, where most households cannot afford to own private automobiles and where it is important to favor resource efficiency.

Using lower-bound estimates of these impacts this study calculates that, in total, sprawl costs the American economy more than $1 trillion annually, or more than $3,000 per capita. The study finds that Americans living in sprawled communities directly bear $625 billion in extra costs, and impose more than $400 billion in additional external costs. Actual costs are probably much higher since the study did not monetize some important impacts, such as the economic costs of farmland and habitat displacement, or the value of improving accessibility for non-drivers.

These costs are economically inefficient and unfair: they waste valuable resources and impose costs on people who do not benefit from sprawl. Described more positively, smart growth policies can provide large savings and benefits, including direct benefits to the people who choose to live in more compact, multi-modal communities, and indirect benefits to society overall.

The study investigated the demand for sprawl, that is, the amount that households prefer sprawl over smart growth and the factors that affect those preferences. Although sprawl provides direct benefits to residents, many of these are social and economic impacts, such as increased sense of safety, security, and status, as opposed to unique features of sprawl, and so can be replicated in more compact and multi-modal neighborhoods. Fortunately, smart growth policies can improve urban safety, security and livability.

The analysis recognizes that housing needs and preferences are diverse; for example, some households need larger homes, want outdoor space for children and pets, or require workshops, studios, and garages for businesses or hobbies. In addition, as residents become more affluent they demand higher quality neighborhoods and transport options, such as attractive streets, minimal noise and air pollution, and convenient and comfortable public transit services. As a result, to be successful, smart growth development must respond to these demands.

A key question for this analysis is the degree that sprawl is economically inefficient, that is, how much sprawl results from policy distortions which favor lower density development and automobile travel over more compact development and more resource-efficient modes. The study investigated various market and planning distortions which encourage sprawl, such as development practices that favor dispersed development over compact urban infill, underpricing of public infrastructure and services in sprawled locations and underpricing of motor vehicle travel. Consumer preference research suggests that with more efficient pricing and more comprehensive and neutral planning many households to choose more compact communities, drive less, and rely more on alternative modes than they currently do. This study identified specific policy distortions that encourage sprawl over smart growth and market-based reforms for correcting them. For example, cities can improve and encourage more compact housing options, reduce or eliminate minimum parking requirements, reduce development and utility fees for compact infill development, charge efficient prices for using roads and parking facilities, apply multi-modal transport planning, and correct tax policies that unintentionally favor sprawl and automobile travel. There are many good examples of cities in both developed and developing countries that are successfully implementing smart growth policies.

Sprawl-Encouraging Market Distortions

Distortions |

Impacts |

Reforms |

|

Restrictions on density, mix, and multi-family housing. |

Reduces development densities and increases housing costs. |

Allow and encourage more compact, mixed development. |

|

High minimum parking requirements. |

Reduces density and discourages infill development. Subsidizes automobile ownership and use. |

Eliminate minimum parking requirements, set maxima, require or encourage parking unbundling. |

|

Underpriced public services to sprawled locations. |

Encourages sprawl. Increases government costs. |

Development and utility fees that reflect the higher costs of providing public services to sprawled locations. |

|

Tax policies that support home purchases. |

Encourages the purchase of larger, suburban homes. |

Eliminate or make neutral housing tax policies. |

|

Automobile-oriented transport planning. |

Favors automobile travel over other modes. Degrades walking and cycling. |

More neutral transport planning and funding. |

|

Transport underpricing (roads, parking, fuel, insurance, etc.). |

Encourage vehicle ownership and use. |

More efficient pricing. |

|

Tax policies that favor automobile commuting. |

Encourages automobile travel over other modes. |

Eliminate parking tax benefits or provide equal benefits for all modes. |

Many current policies favor sprawl and automobile travel over compact development and more resource-efficient modes transport.

The study identified specific market-based polices that support smart growth, such as those listed below.

Policies That Support Smart Growth

- Improved walking, cycling, and public transit in response to consumer demands—such as better sidewalks and better bike and bus lanes on most urban arterials.

- Reduced, more flexible parking requirements and density limits in urban areas.

- More diverse and affordable housing options such as secondary suites.

- Improved public services (e.g., schools, policing, utilities) in smart growth locations.

- Efficient pricing of roads and parking, so motorists pay directly for using these facilities, with higher fees during congested periods.

- Distance-based vehicle registration, insurance, and emission fees.

- Location-based development fees and utility rates so residents pay more for sprawled locations and save with smart growth.

- Vehicle registration auctions in large cities where vehicle ownership should be limited.

- More comprehensive evaluation of all impacts and options in the planning process.

- Accessibility-based planning rather than mobility-based planning, so accessibility is given equal consideration as mobility when evaluating transport impacts.

- Least-cost transport planning, which allocates resources to alternative modes and transportation demand management programs when they are effective investments, considering all impacts.

These smart growth policies reflect market and planning principles such as consumer sovereignty, efficient pricing and neutral planning.

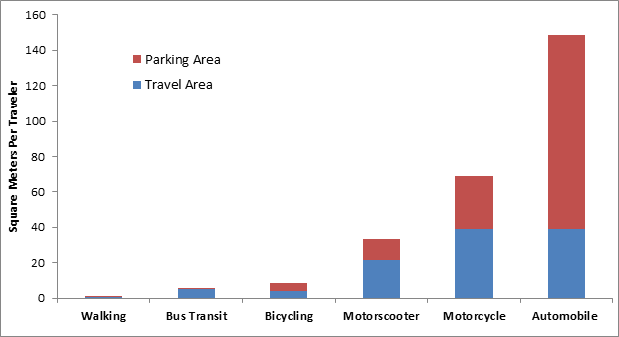

An important and unique feature of this study its analysis of optimal vehicle densities in addition to human densities. Motor vehicles require far more road and parking space than other travel modes. On average each automobile requires 20-60 square meters of road space plus two to six off-street parking spaces averaging about 30 square meters each, totalling between 80 square meters per vehicle in smart growth communities up to 240 square meters in sprawled communities. This means that an automobile typically uses more land than is devoted to an urban resident's house. Increased automobile traffic and the additional road and parking facilities they require increase development costs, stimulates sprawl, creates traffic and parking congestion, displaces greenspace, and increases noise and air pollution. As a result, efforts to increase urban densities, transport system efficiencies, affordability and urban livability require policies that limit private automobile ownership and use to the amount that a city's roadway system can efficiently accommodate.

Space Required By Travel Mode

Automobile travel requires far more road and parking space than other modes due to their size and speed.

To help determine the optimal densities in specific situations, the study divided cities into three categories:

- Unconstrained cities are surrounded by an abundant supply of lower-value lands. They can expand significantly. This should occur on major corridors and maintains 30 residents per hectare densities. A significant portion of new housing may consist of small-lot single-family housing, plus some larger-lot parcels to accommodate residents who have space-intensive hobbies, such as large-scale gardening or owning large pets. Such cities should maintain strong downtowns surrounded by higher-density neighborhoods with diverse, affordable housing options. In such cities, private automobile ownership may be common but their use should be discouraged under urban-peak conditions by applying complete streets policies (all streets should include adequate sidewalks, crosswalks, bike lanes and bus stops), transit priority features on major arterials, efficient parking management, and transport pricing reforms that discourage urban-peak automobile travel.

- Semi-constrained cities have a limited ability to expand. Their development policies should include a combination of infill development and modest expansion on major corridors. A significant portion of new housing may consist of attached housing (townhouses) and mid-rise multi-family. Such cities should maintain strong downtowns surrounded by higher-density neighborhoods. In such cities, private automobile ownership should be discouraged, with policies such as requiring vehicle owners to demonstrate that they have an off-street parking space to store their car, pricing of on-street parking with strong enforcement, roadway design that favors walking, cycling and public transit, and road pricing that limits vehicle travel to what their road system can accommodate.

- Constrained cities cannot significantly expand, so population and economic growth requires increased densities. In such cities, most new housing will be high-rise and few households will own private cars. Such cities require strong policies that maximize livability in dense neighborhoods, including well-designed streets that accommodate diverse activities; adequate public greenspace (parks and trails); building designs that maximize fresh air, privacy and private outdoor space; transport policies that favor space-efficient modes (walking, cycling and public transit); and restrictions on motor vehicle ownership and use, particularly internal combustion vehicles.

This analysis indicates that very high regional densities (more than 100 residents per hectare) are only justified in highly constrained cities such as Hong Kong and Singapore. Most smart growth benefits can be achieved by shifts from low (under 30 residents per regional hectare) to moderate (50-80 residents per regional hectare, which is typical of affluent European cities). Contrary to a common criticism, smart growth does not require that everybody live in high-rise apartments; this analysis indicates that, except in the most constrained cities, efficient urban development allows most households that have young children or pets, or enjoy gardening, the option of choosing single-family or attached housing. However, cities such as Singapore and Seoul demonstrate that with good planning, high density neighborhoods can be very livable, and all cities should have a few high density districts around their downtowns and other major transit terminals.

Because motor vehicles are very space-intensive, vehicle densities are as important as population densities. As a result, a key factor for creating efficient and livable cities is to limit urban automobile ownership and manage roads and parking for maximum efficiency. This requires an integrated program of improvements to space-efficient modes (e.g., walking, cycling, ridesharing, and public transit), incentives for travelers to use the most efficient mode for each trip, and accessible, multi-modal development that minimizes the need to drive. Since a bus lane can carry far more passengers than a general traffic lane, an efficient city provides bus lanes on most urban corridors.

An important challenge facing growing cities is to provide affordable housing that responds to low-income residents' needs. Lower-priced housing should be diverse, including some larger units for large, extended families, and flexible lofts for households that need workspace for artistic or business activities. Affordable housing should be dispersed around the city to avoid concentrating poverty. In some cities, affordable housing policies may include formalizing informal settlements, or making small parcels of serviced land available for sale or lease, on which owners build their houses. In most growing cities, a major portion of affordable housing should consist of mid-rise (2-6 story), wood-framed apartments and townhouses, generally built by private developers with government support. In highly constrained cities, affordable housing may require government subsidies of high-rise apartments.

Optimal Urban Expansion, Densities and Development Policies

Factor |

Un-Constrained |

Semi-Constrained |

Constrained |

|

Growth pattern |

Expand as needed |

Expand less than population growth |

Minimal expansion |

|

Optimal regional density (residents / hectare) |

20-60 |

40-100 |

80 + |

|

Housing types |

A majority can be small-lot single-family and adjacent |

Approximately equal portions of small-lot single-family, adjacent, and multi-family. |

Mostly multi-family |

|

Optimal vehicle ownership (vehicles per 1,000 residents) |

300-400 |

200-300 |

< 200 |

|

Private auto mode share |

20-50% |

10-20% |

Less than 10% |

|

Portion of land devoted to roads and parking |

10-15% |

15-20% |

20-25% |

|

Examples |

Most African and American cities. |

Most European and Asian cities. |

Singapore, Hong Kong, Male, Vatican City. |

Different types of cities should have different growth patterns, densities and transport patterns, based on their ability to expand.

In all types of cities it is important to ensure that compact urban neighborhoods are very livable and cohesive by designing urban streets to be attractive and multi-functional (including sidewalks, shops, cafes, landscaping and awnings), building public parks and trails, and providing high quality public services (policing, schools and utilities), and encouraging positive interactions among residents (local festivals, outdoor markets, recreation and cultural centers, etc.).

Critics have responded to this study (see, for example, comments in these Economist, Washington Post, and Streetsblog articles concerning our report), by arguing that sprawl provides benefits in addition to costs, and that planners should not dictate the type of housing that resident choose. They are correct on both points, but their criticisms are based on false assumptions about this study's analysis and conclusions. In fact, this study does recognize the benefits of sprawl—it discusses them in detail. However, these are mostly direct benefits to residents of sprawling communities, such as increased private greenspace (lawns and gardens), and more privacy and quiet. There is no reason to believe that there are significant external benefits of sprawl (non-residents benefit from increased sprawl) that would offset the substantial external costs, since rational economic agents (people and businesses) externalize costs and internalize benefits. If sprawl provided external benefits, somebody would capture them, for example, by negotiating a subsidy. This study emphasizes market-based solutions which tend to increase housing options and test consumers' willingness-to-pay, such as reduced and more flexible off-street parking requirements, and cost-based pricing of roads, parking facilities and urban-fringe services.

The study's key finding is that virtually everybody can benefit if, through good policies and design, cities can make resource-efficient housing and transport options more attractive, resulting in the best of all worlds: urban communities that are livable and productive in addition to protecting the global environment.

Planetizen Federal Action Tracker

A weekly monitor of how Trump’s orders and actions are impacting planners and planning in America.

Chicago’s Ghost Rails

Just beneath the surface of the modern city lie the remnants of its expansive early 20th-century streetcar system.

San Antonio and Austin are Fusing Into one Massive Megaregion

The region spanning the two central Texas cities is growing fast, posing challenges for local infrastructure and water supplies.

Since Zion's Shuttles Went Electric “The Smog is Gone”

Visitors to Zion National Park can enjoy the canyon via the nation’s first fully electric park shuttle system.

Trump Distributing DOT Safety Funds at 1/10 Rate of Biden

Funds for Safe Streets and other transportation safety and equity programs are being held up by administrative reviews and conflicts with the Trump administration’s priorities.

German Cities Subsidize Taxis for Women Amid Wave of Violence

Free or low-cost taxi rides can help women navigate cities more safely, but critics say the programs don't address the root causes of violence against women.

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.

planning NEXT

Appalachian Highlands Housing Partners

Mpact (founded as Rail~Volution)

City of Camden Redevelopment Agency

City of Astoria

City of Portland

City of Laramie