As an emerging area of sustainable practice, Low Impact Development's current one-size-fits-all application is inadequate to effectively fulfill its guiding principles, writes Jonathan Ford, who proposes five LID planning and design strategies for achieving great places in balance with nature.

Low Impact Development (LID)is a growing area of practice at the intersection of Planning, Ecology, Landscape Architecture, and Civil Engineering. LID is an approach to land development (or re-development) that works with nature to manage stormwater as close to its source as possible in order to reduce the impact of built areas on the environment and promote the natural movement of water.

Low Impact Development has emerged as the preferred sustainable site design methodology. However, LID's current, one-size-fits-all application is inadequate to effectively fulfill its guiding principles:

- Reduce impervious cover;

- Prevent impacts to natural systems;

- Manage water close to the source;

- Utilize less complex, non-structural Best Management Practices (BMPs); and

- Create a multi-functional landscape.

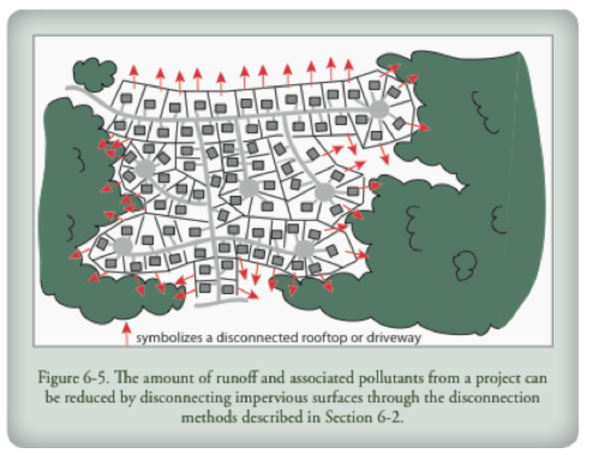

Consider the following LID examples featured as case studies in current New England state stormwater manuals:

These examples present halfway solutions – the application of a layer of Low Impact Development technology to the same sprawling, disconnected land use patterns. If instead we are to create and protect truly lovableplaces in balance with nature, we must incorporate such elements as watershed boundaries, neighborhood context, character of the built environment, future growth projections, stakeholder vision, and last but certainly not least, nature's own cues.

If we are going to create and protect cherished places that are in balance with nature, Low Impact Development must evolve towards a more holistic, fine-grained approach, integrated with land use patterns and neighborhood context. To foster this evolution, we propose the following five planning and design strategies for achieving great places in balance with nature.

Strategy #1 – Not all impervious areas are created equal.

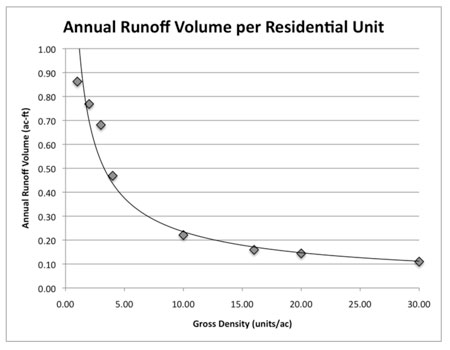

Not all impervious areas are the enemy of watershed health. Compact, walkable development and the accompanying preservation of contiguous natural resources can dramatically reduce the total impervious area within a watershed when compared with conventional lower-density development patterns (EPA, 2006).

In other words, for a given buildout, compact development typically requires far less total impervious area per capita – less streets, less parking surfaces, less building roof area – than the same buildout using typical Conventional Suburban Development (CSD) patterns. This leads to a decrease in stormwater runoff volume and pollutant loadings within the watershed, not to mention savings in infrastructure construction and maintenance costs (Morris Beacon Design, 2010).

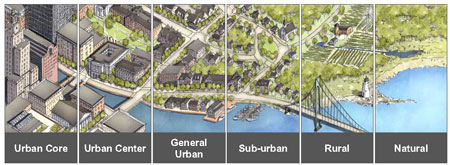

To support implementation and preservation of compact neighborhoods, designers must understand the connection between their site design strategies and the rural-urban transectin the neighborhood they are working. It is important not to burden higher density development with overly onerous landscaping, open space, or stormwater management requirements. Vibrant, walkable places are by their very nature compact with relatively higher density, and this is where significant per capita watershed improvement is achieved.

On the other hand, projects located near a neighborhood edge or projects that don't fit within a New Urbanist/Smart Growth land use framework will almost always benefit from full application of "typical" low impact development planning principles including vegetated treatment practices and strategic open space preservation to reduce their watershed impact. In fact, sometimes lower-intensity development should be asked to work harder-- accommodating neighborhood/district scale flood control and increased performance standard requirements that aren't appropriate or technically feasible within compact centers.

Stormwater ordinances and design guidelines tied to zoning codes that encourage compact development present a unique opportunity for communities to reduce their watershed impact AND promote creation of livable, lovable places.

Morris Beacon Design recently completed work on a stormwater ordinance and design guidelines for Simsbury, Connecticut that demonstrates these concepts in practice. The work is unique in its approach, funded by Connecticut Department of Environmental Protection as an LID program, but organizing stormwater management and site design requirements according to the unique built and natural conditions found in Simsbury. The project effectively enables the community vision expressed in the Town's Plan of Conservation and Development and the recently adopted form-based Simsbury Center Code. Specific focus was placed on Simsbury Center, including a Watershed Planning and Design Framework to guide neighborhood-scale planning in conjunction with the Simsbury Center Code. A BMP implementation matrix was calibrated to Simsbury Center form-based zones and a Planning and Site Design Criteria Checklist integrates context sensitive Low Impact and Light Imprint design principles into all projects. Rate/volume/water quality mitigation incentives are proposed for projects within Simsbury Center or other compact, walkable areas within town, and a 10% increase in stormwater mitigation requirements for projects not located in designated compact areas.

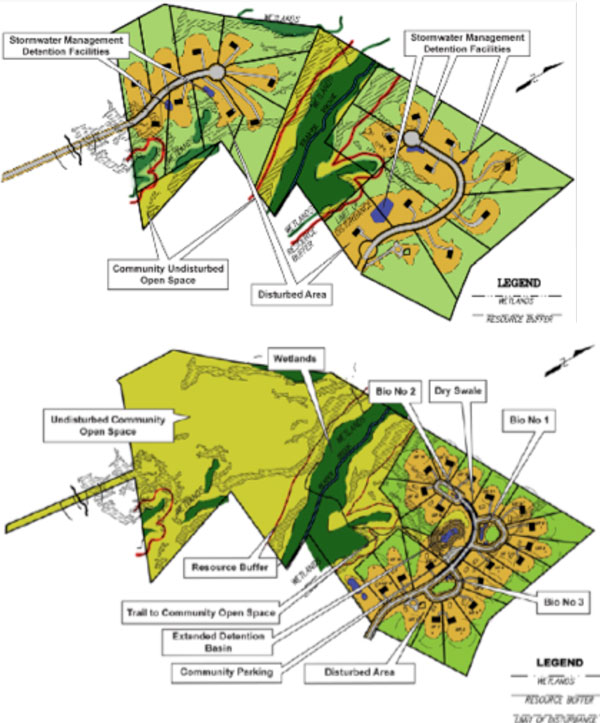

Strategy #2 – Plan with the land.

It is no longer enough to design a project around state-regulated resource areas and deem the resulting plan "green." Review authorities, homebuyers, business owners, and the community at large are pushing environmental issues to the forefront for a variety of environmental, market, and economic reasons.

Much like impervious area, not all undeveloped land contributes equally to the water balance. Sensitive and/or valuable natural resources including wetlands, their buffers, tidal headwaters, drainage patterns, well-draining soils, and mature trees pull more than their weight in terms of natural water balance. When high-performing natural systems are replaced with impervious surfaces and engineered stormwater systems, or even with new "pervious" underperformers, significant contributions to the evapotranspiration and infiltration pieces of the water balance are shifted to surface runoff.

To build places in balance with nature, the design team must understand detailed site conditions before even thinking about streets, blocks, and buildings. Walk the site and map natural resources to supplement the survey base. Only after producing overlays of existing conditions based on the survey and sitewalk should the team move to design. They should then lay out a neighborhood or site framework for the target development program that maximizes preservation of contiguous valuable natural resources already identified. Communities are encouraged to develop checklists requiring this additional existing conditions assessment as a first step in the design process.

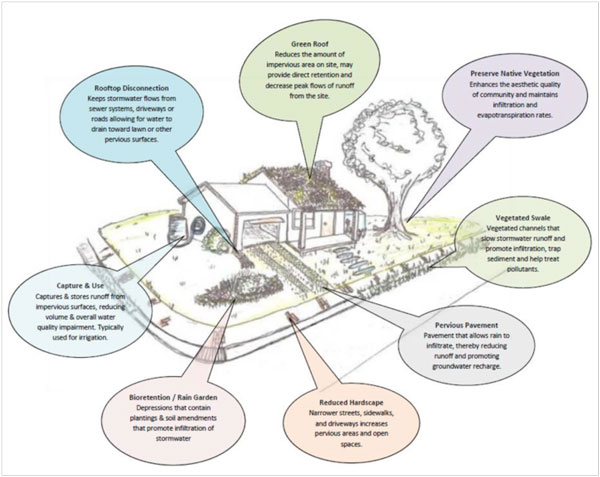

Strategy #3 – Approximate nature.

Assuming the primary intent of a land plan and stormwater mitigation strategy is to approximate pre-development hydrology as closely as possible, three primary quantitative metrics require study: peak rate, volume, and time of concentration. (Of course, treatment for water quality is a fourth). In addition to mitigating the peak rate of runoff from a site as is typically required, stormwater must also be slowed down, naturally filtered, and infiltrated to groundwater as close to where it falls as possible. Even a highly urban site can utilize urban-appropriate site design and best practices to slow, filter, and infiltrate stormwater close to where it falls to approximate nature.

Morris Beacon Design uses this approach as an organizing principle for our site design methodology. This has become especially useful for urban redevelopment/infill sites served by combined sewer systems, as sewer commissions are under intense pressure to reduce flow to their systems and eliminate combined sewer overflows. It should be noted that we do not advocate this approach on an environmental basis alone. Very often a context-appropriate, strategically designed, decentralized stormwater management approach is more cost effective than the conventional pipe-and-pond approach, and also provides additional value as an amenity – a green design feature that resonates with potential buyers if thoughtfully designed and implemented.

Strategy #4 – Design to context.

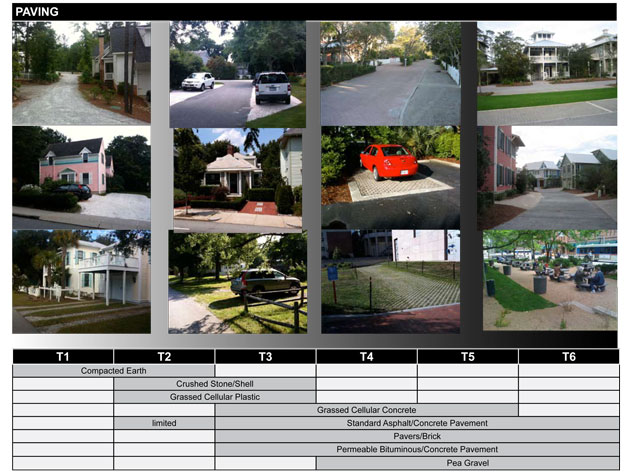

Just like building height, setbacks, floor area ratio, parking standards, and the many other metrics that describe our built environment, stormwater management strategy must also tie to the character of the neighborhood. One size fits all stormwater solutions, even those whose engineering performance is in line with the latest and greatest green "LID" principles, may comply with regulations while at the same time detract from the connectedness and vibrancy of compact neighborhoods. Paving, conveyance, rate/volume, and water quality BMPs must be selected according to urban form and implemented with care to support healthy neighborhoods and to optimize watershed impact.

Ideally the municipality already has established a matrix of Best Management Practices calibrated to the specific range of neighborhood contexts within their limits. Calibration to local conditions is vital. It is impossible to wholesale copy and paste BMP matrices from one place to another. Often guidelines must also cross-reference both geographic/climate considerations and local soil conditions, as strategies for meeting performance standards may need adjustment in coastal areas, cold climates, or in areas with extensive poor-draining soils or high groundwater.

Consideration of retail is another key design parameter that, while it may not be explicitly addressed in stormwater ordinances, is the lifeblood of many of our developer clients. Street and site design must take into account retail visibility and access on a block-by-block scale, or the viability of an entire project may suffer.

Strategy #5: Leave a Simple Solution Behind

The most dazzling technological stormwater management solutions are worthless if they are abandoned after a year because they were too complicated or costly to maintain.

Site sustainability is purely academic if only evaluated as a series of required metrics on paper during the design process. Stormwater management solutions function best on a long-term basis when they are:

- Obvious: surface filters, bioretention, tree filters, green roofs, pervious paving surfaces

- Simple: bioretention, vegetated swales, natural filtration systems and erosion control measures, roof downspout daylighting, rainwater harvesting

- Lovable: landscaping that provides double-duty for stormwater management, green roofs

- Not needed in the first place: compact development, redevelopment/infill, shared parking & reduced parking requirements, appropriate-width streets, minimized ornamental lawn

Clearly a long-term approach takes some extra thought, but through this lens intertwined benefits become apparent. For example, reducing site impervious area by using less intensive minimum parking requirements reduces the stormwater volume/quality load to be mitigated while also reducing infrastructure cost and improving site aesthetics.

Conclusion

Civil engineers are trained to develop solutions that effectively and efficiently address the question at hand. Low Impact Development is a step forward for watershed health, however we must reframe the questions being asked to maximize its application. LID planning and design methodologies melded with urban intensity and neighborhood context will optimize watershed health while creating vibrant, lovable places and protecting the great walkable places we already have.

Jonathan Ford, PE is Principal and Founder of Morris Beacon Design, a New Urbanist civil engineering and planning consulting firm. He is a 2006 Knight Fellow in Community Building at the University of Miami's School of Architecture. Jonathan is also co-founder and past President of the New England Chapter of the Congress for the New Urbanism.

Sources

"Protecting Water Resources with Higher Density Development". US EPA, 2006. http://www.epa.gov/smartgrowth/water_density.htm

"Smart Growth & CSD: An Infrastructure Case Study" Morris Beacon Design, 2010. http://www.morrisbeacon.com/portfolio.php?c=research

Planetizen Federal Action Tracker

A weekly monitor of how Trump’s orders and actions are impacting planners and planning in America.

Maui's Vacation Rental Debate Turns Ugly

Verbal attacks, misinformation campaigns and fistfights plague a high-stakes debate to convert thousands of vacation rentals into long-term housing.

Restaurant Patios Were a Pandemic Win — Why Were They so Hard to Keep?

Social distancing requirements and changes in travel patterns prompted cities to pilot new uses for street and sidewalk space. Then it got complicated.

In California Battle of Housing vs. Environment, Housing Just Won

A new state law significantly limits the power of CEQA, an environmental review law that served as a powerful tool for blocking new development.

Boulder Eliminates Parking Minimums Citywide

Officials estimate the cost of building a single underground parking space at up to $100,000.

Orange County, Florida Adopts Largest US “Sprawl Repair” Code

The ‘Orange Code’ seeks to rectify decades of sprawl-inducing, car-oriented development.

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.

Heyer Gruel & Associates PA

JM Goldson LLC

Custer County Colorado

City of Camden Redevelopment Agency

City of Astoria

Transportation Research & Education Center (TREC) at Portland State University

Jefferson Parish Government

Camden Redevelopment Agency

City of Claremont