Our fair housing laws enshrine an approach that prohibits us from explicitly referring to race, even in programs intended to undo the harm caused by racism. Now restorative housing policy is attempting to directly confront this history.

The era of cellphone videos has forced white America to finally acknowledge the obvious patterns of racial inequity in policing. But in other parts of society we still cling to the idea that racial inequity is the result of “a few bad apples” rather than a core feature of the system itself.

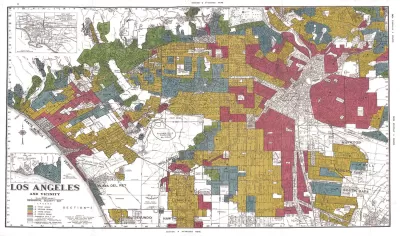

Among the most consequential instances of this willful blindness has been our approach to fair housing. In response to centuries of unjust housing and land use policies (public and private) that target Black people and others specifically based on their race, our fair housing laws enshrine an “all lives matter” approach which actively prohibits us from explicitly referring to race even in programs intended to undo the harm caused by this history.

A new generation of local housing policymakers is attempting to directly confront this history, but fair housing law leads to convoluted policies that offer to further racial equity only indirectly through income or geographic targeting. This attempt to address racial injustice by proxy has become one of the defining failures of housing policy today. Colorblindness is fundamentally at odds with what is strategically and emotionally necessary for us to move forward as a people.

Bearing Witness to a Crime

In 1966, the apartheid regime in South Africa forcibly displaced more than 20,000 people of color from their homes in central Cape Town’s District 6. The area, a dense and racially mixed working-class community with thriving businesses and homes, had been designated a “white area” under the Group Areas Act. Under the law, only white people were allowed to own or rent property in desirably located areas like District 6. Stores and homes were bulldozed to make way for new housing for whites only. People were forcibly relocated at gunpoint (sometimes taking only suitcases) to racially segregated townships on the cape flats, miles from public services and community institutions. Previously District 6 had been home to strong mixed-race community institutions including soccer clubs, musical groups, and churches. But the apartheid system required racial sorting, so these institutions were destroyed along with the buildings of District 6. Social capital built over decades was erased in months.

For Americans, it is easy to see this shameful moment as a violent crime.

What has been harder for Americans to acknowledge is that at the same time...

FULL STORY: Restorative Housing Policy: Can We Heal the Wounds of Redlining and Urban Renewal?

Planetizen Federal Action Tracker

A weekly monitor of how Trump’s orders and actions are impacting planners and planning in America.

Maui's Vacation Rental Debate Turns Ugly

Verbal attacks, misinformation campaigns and fistfights plague a high-stakes debate to convert thousands of vacation rentals into long-term housing.

Restaurant Patios Were a Pandemic Win — Why Were They so Hard to Keep?

Social distancing requirements and changes in travel patterns prompted cities to pilot new uses for street and sidewalk space. Then it got complicated.

In California Battle of Housing vs. Environment, Housing Just Won

A new state law significantly limits the power of CEQA, an environmental review law that served as a powerful tool for blocking new development.

Boulder Eliminates Parking Minimums Citywide

Officials estimate the cost of building a single underground parking space at up to $100,000.

Orange County, Florida Adopts Largest US “Sprawl Repair” Code

The ‘Orange Code’ seeks to rectify decades of sprawl-inducing, car-oriented development.

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.

Heyer Gruel & Associates PA

JM Goldson LLC

Custer County Colorado

City of Camden Redevelopment Agency

City of Astoria

Transportation Research & Education Center (TREC) at Portland State University

Jefferson Parish Government

Camden Redevelopment Agency

City of Claremont