In 2021 New York City rolled out an e-scooter program in some of the city’s most underserved transportation zones, focused on equity and access. Urban planner Thandi Nyambose gives an insider’s view of the program from the ground.

A longer version of this story was originally published by Urban Omnibus, a publication of the Architectural League of New York dedicated to advancing the collective work of citymaking. Sign up to receive weekly features via newsletter.

--

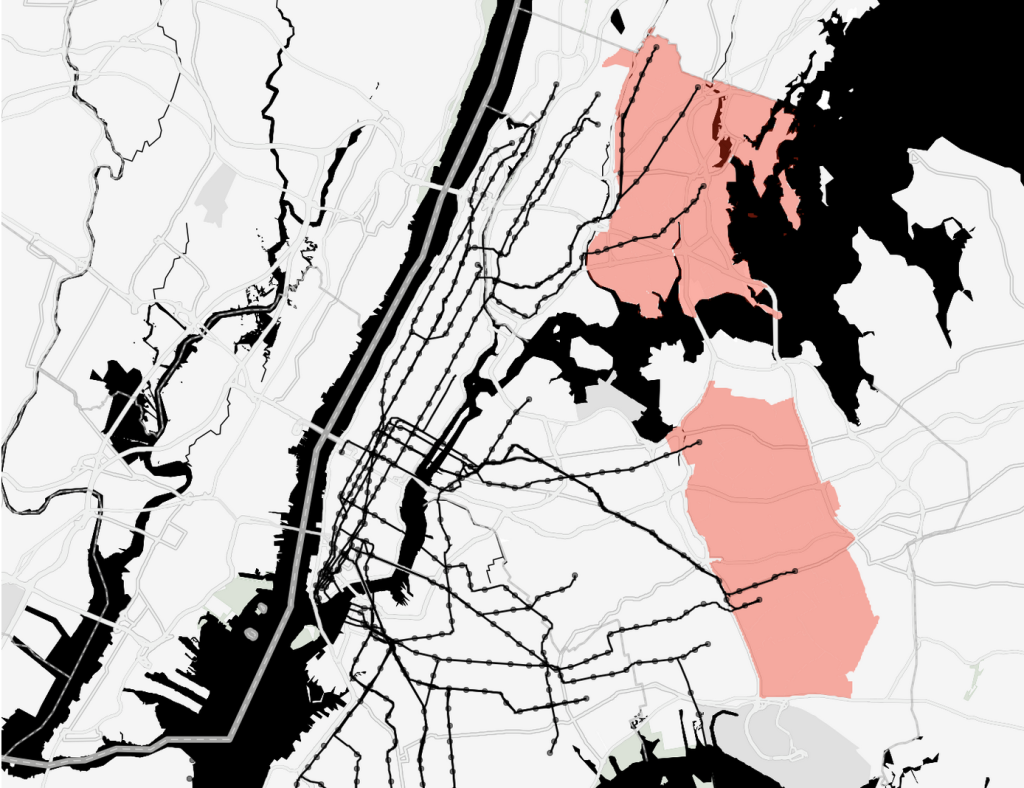

E-scooter shares and other last-mile micromobility systems began rolling out in cities from Santa Monica to Mexico City nearly ten years ago. New York City has been a relatively late adopter, especially at the city’s edges in the northeastern Bronx and eastern Queens. In 2021, the New York City Department of Transportation authorized e-scooter share services in two zones near the ends of MTA subway lines, where riders rely on often unreliable buses to get to their jobs or run errands. Ahead of the program’s launch, the DOT emphasized community participation in locating parking corrals, and equity — launching in outer borough neighborhoods without CitiBike, offering discounted rides to SNAP recipients and NYCHA residents, and hiring hourly employees, rather than gig economy workers, to rebalance scooters throughout the day.

But, as with similar programs nationwide, the initiative has raised the ire of some who are not eager to share streetscapes designed for cars. And with a lack of proper infrastructure — such as hardened bike lanes — how much further can the program go? Urban planner Thandi Nyambose had a front-row seat to the rollout of the Bronx pilot program. Here, she gives us an account of micromobility’s ups and downs in the outer boroughs.

You exit the 5 train at the elevated E 180 Street stop in the Bronx, taking the stairs down to street level. Your apartment is 15 minutes away if you can catch the Bx21 bus, which is supposed to come every ten minutes. Exhausted, you can either wait at the crowded bus stop, or — as of summer 2021 — use an app on your phone to unlock an e-scooter directly underneath the train station and glide the last leg of your trip down the bike lane, whizzing past car traffic on Morris Park Avenue, before pulling up to your home in under nine minutes.

It wasn’t always like this

By the time e-scooters arrived in New York, they had already been deployed in over 150 US cities. As the e-scooter industry boomed in 2017 and 2018, New York City was an obvious candidate for this new mode of transportation. However, both e-scooters and e-bikes with a throttle remained illegal in New York State. Policy makers considered them a safety risk to both pedestrians and riders; while transportation activists, delivery worker coalitions, e-scooter operating companies, and politicians believed e-scooters could also help New York hit its climate targets.

In 2019, the New York City Mayor’s Office of Climate and Environmental Justice declared a 2050 goal that 80 percent of trips within the city be made on a sustainable mode (such as walking, biking, or mass transit), and that the remaining vehicular trips be zero emissions. The strains of the pandemic also pressured cities to promote socially distanced transit and reduce the number of people relying on cramped trains and buses. In June 2020, after years of heated discourse and hundreds of thousands of lobbying dollars, New York State legalized e-scooters and e-bikes.

Equity across the system

By late 2020, the New York City Department of Transportation (NYCDOT) launched a competitive process for a two-year e-scooter pilot program, with the possibility to expand after the first year. The plan emphasized equity and accessibility: As mandated by 2020 Local Law 74, the program would target neighborhoods situated outside CitiBike’s service and planned expansion areas, and those at the margins of the City’s fixed-route transportation networks — areas where subway lines end. Operators — later selected to be Bird, Lime, and Veo — were required to offer heavily discounted pricing for riders for NYCHA residents and SNAP recipients and to provide wheelchair-accessible scooters to people with ambulatory disabilities.

In order to avoid controversy over the new service’s use of public street space, the DOT advocated for parking corrals, which would designate e-scooter parking locations amongst the 99 cent stores, delis, and bodegas.

In early 2021, before the program officially launched, the DOT began an outreach campaign to educate residents and solicit feedback on locations for the corrals. This consisted of virtual meetings, surveys, on-street demos, as well as planning briefings with elected officials, community boards, business improvement districts, hospitals, and partner agencies. The corrals, simple white rectangles painted onto the sidewalks or roadbeds, are generally successful in reducing obstructions on crowded streets. The rest of the system is completely “dockless.” Users can drop scooters off almost anywhere when they’re done, in front of a subway station, store, or home.

The City also mandated operators to hire W-2 workers, as opposed to the gig laborers they largely rely on elsewhere. Seven days a week, fleet managers working for Bird, Lime, and Veo “rebalance” free-floating e-scooters, moving them from low- to high-demand areas like transit hubs and business districts. These same employees are also tasked with conducting on-foot patrols to correct parking violations and maintain tidiness, as well as performing quality checks and minor repairs like brake adjustments, tire inflation, and vehicle cleaning. Across the three New York operators, they are paid an hourly rate in the range of $21–$22 per hour.

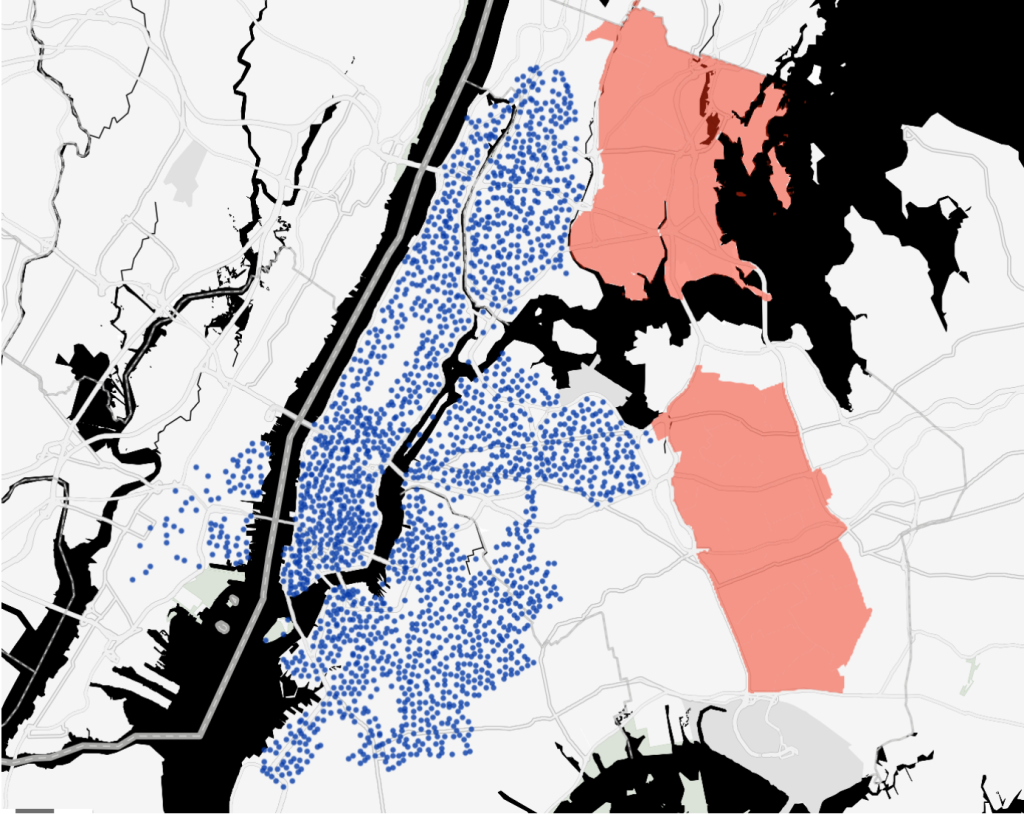

DOT still conducts ongoing outreach to increase ridership and discount enrollment, including in-person community events like helmet giveaways outside NYCHA buildings. Many enrolled in the discount program are repeat riders. Between August 2021 and August 2022, affordable membership riders constituted 1.9 percent of all unique user accounts and 3.8 percent of all e-scooter trips. But there is much work to be done: seven percent of the population in the initial pilot area reside in NYCHA developments, and 21 percent are SNAP recipients.

From pilot to permanent

In June 2022, the City doubled its Bronx coverage area and the total e-scooter count to 6,000. Six months later, the DOT announced that a new RFP would allow interested companies to compete to enter the market and potential additional areas. This marked the end of the pilot, indicating that the City deemed the scooters viable for a longer term, larger program.

In fall 2023, the DOT announced it would add southeast Queens to the patchwork of coverage, working with the same three scooter companies, eventually launching in Flushing, Auburndale, Jamaica, Rochdale Village, and Springfield Gardens.

Four months after the Queens expansion, Bird shared that its Queens e-scooters had completed 250,000 rides, with 65 percent starting or ending within 50 feet of a transit stop. A Queens Twitter user wrote, “As someone who needs a bus to get to the subway station by my house, these things are *amazing.* Instead of waiting 20 minutes for a bus sometimes, I just scoot scoot 🛴 and I’m home in under ten minutes.”

The ever-present question of safety

New York City laws require operators to limit speeds on their e-scooters to 15 mph, though many of the vehicles can go up to 20 mph. Using GPS technology, the Bird, Lime, and Via apps can create bounded areas where e-scooter speeds are capped below the 15 mph limit (like greenways in public parks) or shut off completely in prohibited areas (like Jacobi Medical Campus and Co-op City’s interior roads).

In 2022, 44 percent of all riders who responded to DOT’s e-scooter survey reported riding on the sidewalk, and the reason is simple: 30 percent also reported they felt safer riding on the sidewalk than in the street. On already full New York City sidewalks, like those of Downtown Flushing, this trend feels threatening to some pedestrians and has contributed to a storm of negative PR. Some e-scooters are designed to produce an unpleasant beeping sound when sidewalk riding is detected, or even to automatically slow down to a crawl, but GPS can be distorted by the “urban canyon” effect (signal interference from tall buildings).

A 2022 DOT report concluded that shared e-scooters were widely used, with zero fatalities reported among over 1.3 million trips that year. And for the small number of Bronx e-scooter crashes that were reported, the majority resulted in minor injuries or no injury at all. Just six crashes required admission to a hospital. The same report found that 80 percent of crashes did not involve a collision with another motor vehicle, pedestrian, or bicycle: the majority of e-scooter crashes involved only the rider. These numbers can be improved by creating more connected bike lane networks.

Popular or plague?

Some Bronx corridors have been particularly popular for e-scooters. Morris Park Avenue has a conventional bike lane in both directions as well as access to the 2 and 5 train lines, and two bus lines. The DOT has pledged to prioritize more street improvements within the coverage zones, which lack connected bike paths, to improve on rider experience. Because both e-scooter areas lack safe infrastructure like the protected, or “hardened,” bike lanes found primarily in Manhattan, the issue of sidewalk riding is likely to continue regardless of rider education or cutting-edge sidewalk-riding detection tech.

Despite prevention efforts, parked e-scooters continue to materialize in the middle of the sidewalk creating a tripping hazard and obstacle for strollers and wheelchairs. At roughly 50 pounds, the e-scooters are awkward or impossible to move if left blocking a building entrance or a driveway, especially for elderly and disabled people.

More extreme examples of mis-parked scooters range from e-scooters abandoned next to freeways at the borders of the coverage area to e-scooters submerged in the Bronx River. Between July 2023 and September 2024, the Bronx River Alliance reported pulling 410 e-scooters and e-bikes out of the river, presumably after bored teenagers or frustrated residents pushed the parked vehicles down the hill into the water. This pollutes an already precarious urban river ecosystem and costs the companies — as well as non-profits like the Bronx River Alliance — money and time to remove. Veo temporarily paused service along the river in summer 2024 to deter this, which meant removing access to one of the only protected bike lanes in the Bronx service. Streetsblog reported:

“A Wakefield resident … with more than 1,200 trips under his belt told the Bronx Times removing access to the bike lanes along the Bronx River Parkway and Bronx Boulevard — which feel safer to travel on than other nearby options — was ‘one of the worst things Veo could have done.’ . . . ‘Going through Bronx Park is like the safest way for me,’ he said. ‘Every other street is riddled with potholes, people double parking, the sidewalks are narrow, so even if I was to ride on the sidewalks for safety, it’s hard to do that.'”

Local elected officials have pushed back on e-scooters in their neighborhoods, placing the newest phase of the program at risk. In October 2024, City Council Speaker Adrienne Adams wrote to the DOT requesting an immediate operational pause for the entire Queens area. Soon after, Republican Council member Kristy Marmorato called on Mayor Eric Adams to terminate operations in her Bronx district. Frustrations surrounding the clutter of the free-floating parking model quickly became a topic at Queens Community Board meetings. Qns.com quoted one resident lamenting that lawless e-scooters were “invading the neighborhood.” After just three months, Queens Council member James Gennaro denounced the program as “a total disaster.” He added “These e-scooters are a blight. They are a menace.” As of now, there is no sign of either program stopping.

A future for micromobility in the boroughs?

In spite of opposition, ridership continues to grow. With 650,000 trips and over 40,000 new accounts created in the Queens area in 2024, riders took up scootering to get home from school, commute to work, and shop. In January 2025, Lime announced that 2024 was its most successful year in the Bronx, with approximately 1.49 million rides across 59,000 riders. That’s a 55 percent increase in total rides compared to the previous year. Rides for both consistently average about one mile per trip, and the vast majority of trips start and end in the same neighborhood, illustrating that the program is primarily serving local residents, as intended.

This level of usage, often in less-than-ideal riding conditions, has shone a light on New Yorkers’ appetite for micromobility. August 2025 will mark four years of shared e-scooter operations in New York, throughout which the DOT has promised to build on the program’s momentum with dozens of capital improvements like hardening bike lanes and network expansions.

Most recently, in an effort to improve conditions for delivery workers, the Adams administration shared an Electric Micromobility Action Plan, with a section devoted to comprehensive street design. The potential for shared e-scooters could be vast: think borough-wide, multimodal trips, where subway or train networks can reach deeper into communities so residents can scoot from home to appointments without paying for a rideshare or burning a single fossil fuel.

But with no comprehensive plan for infrastructural improvements from the DOT or from the operators to address user compliance, the future for our current riders is a murky one, and the skeptical onlookers will most likely remain skeptical.

All photos copyright Abigail Montes.

All maps by Thandi Nyambose.

Thandi Nyambose is a dancer and urban planner with a background in public health and transportation. She holds a Master of Urban Planning from Harvard Graduate School of Design. Thandi is currently a Project Manager at Circuit, where she designs and implements electric shuttle programs across the Northeast. Prior to joining Circuit, Thandi managed Bird’s shared micromobility programs, including NYC’s first electric scooter program in the East Bronx.

Planetizen Federal Action Tracker

A weekly monitor of how Trump’s orders and actions are impacting planners and planning in America.

Vehicle-related Deaths Drop 29% in Richmond, VA

The seventh year of the city's Vision Zero strategy also cut the number of people killed in alcohol-related crashes by half.

As Trump Phases Out FEMA, Is It Time to Flee the Floodplains?

With less federal funding available for disaster relief efforts, the need to relocate at-risk communities is more urgent than ever.

A Case for Universal Rental Assistance

A pair of researchers argues that expanding rental assistance programs for low-income households is the most effective way to alleviate the housing crisis.

Office Conversions Have Increased Every Year This Decade

Since the pandemic, office vacancy rates remain high, leading many cities to adjust zoning codes to accommodate adaptive reuse.

Index Measures Impact of Heat on Pedestrian Activity

When heat and humidity are high, people are more likely to opt for cars when possible.

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.

JM Goldson LLC

Custer County Colorado

Sarasota County Government

City of Camden Redevelopment Agency

City of Astoria

Transportation Research & Education Center (TREC) at Portland State University

Camden Redevelopment Agency

City of Claremont

Municipality of Princeton (NJ)