What can we learn from the COVID-19 pandemic to help plan more resilient communities that can respond to all types of economic, social, and environmental shocks?

The following is an excerpt from my new report, Pandemic-Resilient Community Planning: Practical Ways to Help Communities Prepare for, Respond to, and Recover from Pandemics and Other Economic, Social and Environmental Shocks. It follows my recent columns, "Lessons from Pandemics: Comparing Urban and Rural Risks" and "Lessons from Pandemics: Transportation Risks and Safety Strategies." Please let me know what you think of this analysis, and if there are more ways that planners can help communities prepare for life's uncertainties.

A basic test of human intelligence is whether we can learn from previous experiences to solve new problems. The COVID-19 pandemic has much to teach us about planning communities that are better prepared for future pandemics and other economic, social and environmental shocks.

Disasters come in many forms and create many types of problems. For example, the 1906 San Francisco earthquake began with an earthquake which created panic and confusion, uncontrolled fires, overwhelmed transportation and medical services, loss of utilities leading to communications failures and water shortages, severe thirst and hunger, homelessness and inadequate shelter, reports of lawlessness that justified martial law (police and soldiers were instructed to shoot looters on sight) leading to accusations of brutality, plus reports of racism and excessive suffering by poor people.

Similarly, a century later, hurricanes Katrina and Rita both began with hurricanes that lead to infrastructure damage, flooding, civil disorder, fires, toxic chemical dispersion, disease risk, and thousands of people isolated for days without water, food or medical care. The damage cause by these storms was exacerbated by structural problems like institutional racism, poverty, inadequate infrastructure, environmental degradation, and automobile-dependent planning. These two examples indicate that our ability to respond to major disasters progressed little in a century. Surely, we can do better!

There are many types of disasters. Each is unique, but there are general lessons we can apply to better prepare for future economic, social and environmental shocks. This includes emergency response planning, which creates specific systems and resources for responding to disasters, plus resilience planning which refers to preparing for diverse economic, social and environmental shocks, or as William Shakespeare described, "the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune."

Disaster Type |

Scale |

|

Earthquake |

Large |

|

Tsunami |

Large |

|

Extreme weather (hurricanes, tornadoes, flooding, blizzards, ice storms, etc.) |

Varies |

|

Drought |

Large |

|

Pandemic |

Very Large |

|

War/civil unrest |

Varies |

|

Wildfire |

Small to Medium |

|

Major utility failures |

Small to Large |

|

Chemical spill/fire |

Small to Medium |

|

Economic Shock (Recession) |

Large |

Although there is extensive literature on emergency management and community resilience planning, most existing publications focus on environmental threats such as hurricanes, earthquakes and wildfires. Pandemics receive little consideration. Pandemics differ from most other disasters because they threaten people not infrastructure, have long durations, and huge economic impacts. The COVID-19 pandemic created an interrelated set of problems that include fear and confusion, risks of illness and deaths, healthcare system stress, travel restrictions, isolation and quarantine requirements, mental and physical stresses, plus lost income to individuals, businesses and governments which threaten local, national and global economies.

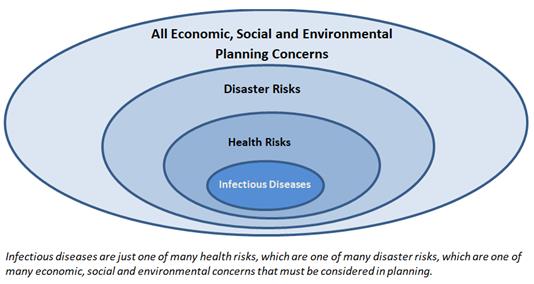

We can learn from this experience, but it is unlikely that our next shock will be the same as this one. It is important to generalize the lessons we learn from COVID-19, so we are better prepared for all types of risks, not just pandemics. Infectious diseases are just one of many health risks, which are one of many disaster risks, which are one of many economic, social and environmental concerns that must be considered in planning.

Principles of Resilience

The future is unpredictable so smart planning prepares for possible unexpected changes, what economists call shocks, or as my grandmother recommended, we should "hope for the best but prepare for the worst." This would be easy if we faced just one possible shock, but there is a large range of possible threats that individuals and communities may face.

Several existing publications provide guidance for resilient community planning, but most are limited in scope; they either reflect an engineering perspective which focuses on physical infrastructure, or additional environmental risks caused by climate change. These are useful but incomplete. They tend to overlook economic stresses, and therefore the need to improve affordable housing and transport options, and they tend to give little consideration to the special needs of vulnerable populations, such as people who are homeless or poorly housed, or have physical or mental health risks, and non-drivers located in automobile-dependent areas.

The 100 Resilient Cities Program and the "Draft Interagency Concept for Community Resilience Indicators and National-Level Measures" explicitly consider a broader range of risks, including chronic stresses such as unemployment, inefficient transport systems, violence and shortages of healthy food and water.

Acute Shocks |

Chronic Stresses |

|

Sudden, sharp events that threaten a community. |

Gradual shocks that weaken the fabric of a community. |

|

|

Here are general principles for creating more resilient communities that can respond effectively to economic, social and environmental shocks:

Prepared and Responsive

Prepared and responsive means that communities have trustworthy leadership, effective emergency management programs, and good communication that allows public officials to communicate with residents and residents to communicate with public officials.

Robust, Secure, Redundant, and Flexible

Critical infrastructure must be strong, redundant, and flexible to withstand potential stresses and failures, and should avoid higher-risk locations. For example, earthquakes cause much less damage and casualties in areas with strong building codes, and extreme weather is less likely to cause power failures where utility lines are underground. Similarly, for security sake, homes and communities should avoid vulnerable floodplains, shorelines, and forests susceptible to wildfires, risks that are increasing with climate change.

Diversity

Diverse systems are better able to respond to unexpected changes. For example, people who normally travel by automobile should value having alternatives, such as good walking, bicycling and public transport in their community, for possible future situations in which they cannot or should not drive, because of a vehicle failure, medical problem or lost income, or because a disaster makes roads impassable or fuel unavailable. Drivers also benefit from non-auto modes that reduce their chauffeuring burdens. Similarly, households benefit from having diverse home heating and cooking options, food supplies, and employment opportunities.

Affordable and Resource-Efficient

If we are lucky, we will always be affluent, but we should prepare for the possibility that sometime we will be impoverished and need more affordable options. Since housing and transportation are most household’s two largest expenses, affordable housing and transportation are particularly important for resilience planning.

These principles can be applied to many types of planning decisions. For example, this suggests that to increase resilience, households should choose homes, and communities should design neighborhoods, that are in lower-risk locations, with efficient and redundant public infrastructure, and build multi-modal transportation systems that provide convenient access to important services and activities without requiring an automobile. These principles also suggest that communities should ensure that affordable housing and transportation options are available, so any household, including those with low incomes, physical impairments or other special needs, can find suitable affordable homes in a walkable neighborhood.

To improve resilience, communities need effective emergency response programs, contagion control, adequate housing for all residents, physical and mental support for isolated people, and affordability. Some contagion control strategies help achieve other public health objectives or other sustainability goals, as summarized in the following table. For example, improving active transport (walking and bicycling), reducing homelessness, affordable infill development, and targeted assistance to low-income households are examples of win-win solutions: they respond to the current pandemic and help achieve other strategic community goals.

Benefits Provided by Various Policies

Policy Solutions |

Reduce Contagion |

Public Health |

Sustainability |

|

Limit public gatherings and activities |

X |

||

|

Targeted cleaning and hygiene |

X |

X |

|

|

Improve public health and emergency services |

X |

X |

|

|

Active Transport (walking and bicycling) improvements |

X |

X |

X |

|

Encourage public transport use |

X |

X |

|

|

Reduce private auto travel |

X |

X |

|

|

Reduce homelessness |

X |

X |

X |

|

Affordable infill housing |

X |

X |

X |

|

Traffic safety programs |

X |

||

|

Assist low-income households |

X |

X |

X |

Policy solutions vary in their scope of benefits. Smart planning favors solutions that also help achieve multiple goals, such as pandemic control policies that support other public health and sustainability objectives.

Pandemics are just one of many risks communities face, and not necessarily the most important, so it would be inefficient to implement contagious disease control strategies that increase other problems, for example, by reducing physical activity which increases cardiovascular disease, or increasing vehicle travel and therefore traffic casualties and pollution emissions. There are many win-win strategies that provide multiple benefits. Eliminating homelessness, improving active transport (walking and bicycling), and creating more affordable housing and transport options help respond to COVID-19 pandemic needs, and provide other benefits, and so help increase overall community resilience.

Human intelligence allows us to generalize lessons from previous experiences to solve new problems. The COVID-19 pandemic is a good learning experience. The bad news: we face diverse and unpredictable risks, with no simple solutions. You can run, but you cannot hide. The good news: cooperative actions can greatly reduce deaths. Given appropriate support, we can be healthy and happy when confronted with economic, social, and environmental shocks.

Information Resources

FEMA (2018), Planning for a Resilient Community, Federal Emergency Management Administration.

FEMA (2016), Draft Interagency Concept for Community Resilience Indicators and National-Level Measures, Federal Emergency Management Administration.

Yosef Jabareen (2012), “Planning the Resilient City: Concepts and Strategies for Coping with Climate Change and Environmental Risk,” Cities, Vol. 31, pp. 220-229 (https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2012.05.004).

Todd Litman “Lessons From Katrina and Rita: What Major Disasters Can Teach Transportation Planners,”Journal of Transportation Engineering, Vol. 132, January 2006, pp. 11-18.

NIST (2015), NIST Community Resilience Planning Guide for Buildings and Infrastructure Systems, National Institute for Standards and Technology.

Planetizen Federal Action Tracker

A weekly monitor of how Trump’s orders and actions are impacting planners and planning in America.

Map: Where Senate Republicans Want to Sell Your Public Lands

For public land advocates, the Senate Republicans’ proposal to sell millions of acres of public land in the West is “the biggest fight of their careers.”

Restaurant Patios Were a Pandemic Win — Why Were They so Hard to Keep?

Social distancing requirements and changes in travel patterns prompted cities to pilot new uses for street and sidewalk space. Then it got complicated.

Platform Pilsner: Vancouver Transit Agency Releases... a Beer?

TransLink will receive a portion of every sale of the four-pack.

Toronto Weighs Cheaper Transit, Parking Hikes for Major Events

Special event rates would take effect during large festivals, sports games and concerts to ‘discourage driving, manage congestion and free up space for transit.”

Berlin to Consider Car-Free Zone Larger Than Manhattan

The area bound by the 22-mile Ringbahn would still allow 12 uses of a private automobile per year per person, and several other exemptions.

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.

Heyer Gruel & Associates PA

JM Goldson LLC

Custer County Colorado

City of Camden Redevelopment Agency

City of Astoria

Transportation Research & Education Center (TREC) at Portland State University

Camden Redevelopment Agency

City of Claremont

Municipality of Princeton (NJ)