Donald Shoup, Quan Yuan, and Xin Jiang guest blog about their recent article in the Journal of Planning Education and Research.

Many low-income neighborhoods have two serious problems: overcrowded on-street parking and undersupplied public services. One policy can address both problems: charge for on-street parking to manage demand and use the resulting revenue to finance local public services.

Charging the right price for on-street parking is the best way to manage demand, and the right price is the lowest price that will produce one or two open parking spaces on every block. New technologies such as such as occupancy sensing and meters that can charge variable prices have solved the practical problems of charging the right price for curb parking, and all the remaining problems are political. To solve the political problems, some American cities have created Parking Benefit Districts where they dedicate the meter revenue to pay for neighborhood public services on the metered streets. The merchants buy into the parking meters because they have been bought off with the meter revenue.

Will Parking Benefit Districts work in other countries? To help answer this question, in our recent JPER article we examine the case of hutongs, the narrow alleys in historic neighborhoods in Beijing, China. In hutongs, illegal parking has become a widespread practice tolerated by the authorities (Figure 1). The share of cars parked illegally in Beijing has been estimated to be as high as 45 percent. Cars often block traffic and occupy much of the space planned for cyclists and pedestrians.

While most hutongs in Beijing have running water, electricity, and even internet access, many do not have sanitary sewer connections. The residents must therefore use public toilets, which are often unsanitary. We examine whether charging for on-street parking can yield enough revenue to provide clean public toilets.

We have an example, the Xisi North 7th Hutong, where Beijing piloted a program to regularize parking and provide public services. The hutong is a typical alley with 247 households and about 660 residents. The regularization part of the program aims to prevent illegal parking, remove obstacles used to secure vacant parking spaces, and reserve parking spaces for alley residents (Figure 2). The pilot program also improves public services by providing public toilet cleaning, 24-hour security patrol, trash collection and landscaping.

Parking is free in the pilot program in the Xisi North 7th Alley. Subsidies from the Subdistrict government pay to provide the public services. We can, however, estimate whether parking charges could replace the subsidy for the pilot program. The capital costs of the program totaled about $62,000. The operating costs are about $24,600 a year. We estimate that market prices for permits to park in the alley could generate market price-based total annual revenue of about $50,000. Thus the payback period for the capital investment is about 2.5 years. This result suggests that the program can be self-financing and is replicable in other neighborhoods.

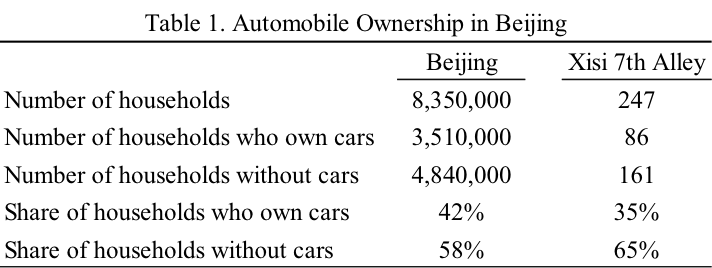

To examine the political feasibility of charging for parking to finance public services, we examined the demographics of people and cars in 7th Alley (Table 1). Only 35 percent of households own a car. The other 65 percent who are carless will receive better public services without paying anything, and they outnumber the car owners almost 2-to-1. If the carless majority prefer public services to free parking, a Parking Benefit District may be politically feasible.

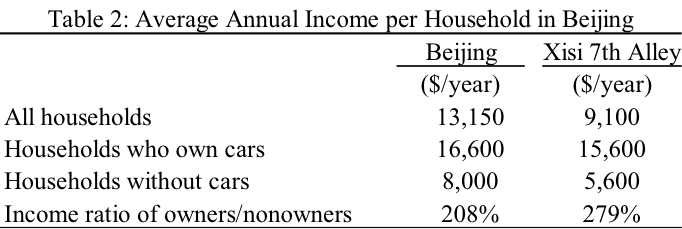

Will charging for parking place an unfair burden on lower-income residents? In Beijing, car-owning households have more than twice the income of carless households (Table 2). In 7th Alley, they have almost three times the income of carless households. Charging for parking and spending the revenue for public services will therefore transfer income from richer to poorer households.

Parking Benefit Districts are most appropriate in dense neighborhoods where (1) on-street parking is overcrowded, (2) public services are undersupplied, (3) most residents park off-street or do not own a car, and (4) residents who do own a car have higher incomes. Where these criteria are met, any city should be able to offer a pilot program to charge for parking and use the revenue to finance public services. Residential Parking Benefit Districts may turn out to be a fair, efficient, and politically feasible way to improve cities, transportation, the economy, and the environment, one parking space at a time.

Open Access Until January 31, 2017

Planetizen Federal Action Tracker

A weekly monitor of how Trump’s orders and actions are impacting planners and planning in America.

Congressman Proposes Bill to Rename DC Metro “Trump Train”

The Make Autorail Great Again Act would withhold federal funding to the system until the Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority (WMATA), rebrands as the Washington Metropolitan Authority for Greater Access (WMAGA).

DARTSpace Platform Streamlines Dallas TOD Application Process

The Dallas transit agency hopes a shorter permitting timeline will boost transit-oriented development around rail stations.

Renters Now Outnumber Homeowners in Over 200 US Suburbs

High housing costs in city centers and the new-found flexibility offered by remote work are pushing more renters to suburban areas.

The Tiny, Adorable $7,000 Car Turning Japan Onto EVs

The single seat Mibot charges from a regular plug as quickly as an iPad, and is about half the price of an average EV.

Supreme Court Ruling in Pipeline Case Guts Federal Environmental Law

The decision limits the scope of a federal law that mandates extensive environmental impact reviews of energy, infrastructure, and transportation projects.

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.

Municipality of Princeton

Roanoke Valley-Alleghany Regional Commission

City of Mt Shasta

City of Camden Redevelopment Agency

City of Astoria

Transportation Research & Education Center (TREC) at Portland State University

US High Speed Rail Association

City of Camden Redevelopment Agency

Municipality of Princeton (NJ)