As extreme weather forces more Americans to relocate to safer areas, this climate-driven displacement impacts not just those who flee high-risk areas, but also the communities they can displace from their new homes.

Recent extreme events like devastating wildfires from Canada to Chile and immensely powerful storms such as Hurricane Ida serve as sobering reminders that climate change is causing harsher, more frequent natural disasters worldwide. From severe flooding in China, Dubai, and Los Angeles to unprecedentedly high temperatures in the United States, the Mediterranean, and Asia, concern is growing about the monetary, environmental, and social costs of climate change.

As of 2024, the United States alone has experienced 383 recorded weather and climate disasters with financial losses exceeding $1 billion. These events are becoming so frequent and costly that, either by choice or by force, people are beginning to migrate from areas with high climate risk, resulting in climate gentrification.

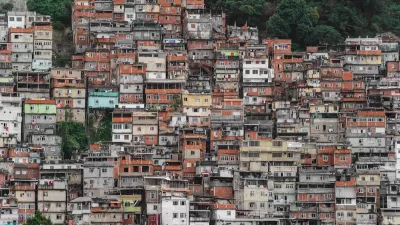

Climate gentrification happens when a population living in a high-risk area is motivated to move to an area with comparatively lower climate risk, known as a “receiving community,” driving up demand for housing and services The potential displacement of longtime residents creates an urgent need to avoid and minimize the adverse effects of this phenomenon.

Individual and institutional property owners in search of reprieve from the mounting cost of maintenance and repair, as well as risk to life and wellbeing, are seeking locations with a lower risk to climate change-related impacts. A 2022 study by Redfin found that homebuyers who have access to flood risk information when browsing home listings are more likely to view and make offers on homes with lower flood risk.

Unfortunately, not all of those affected or displaced by impacts such as flood, fire, and storms have a choice in where they settle, nor are they guaranteed resources to ensure their recovery from the shock of relocation. Also, similarly vulnerable groups in the areas people are migrating to may be ill-equipped to adapt to the neighborhood change that accompanies an influx of new populations and rising investment.

If left unaddressed, the adverse impacts of climate gentrification will only exacerbate existing wealth disparities, alter community dynamics, and reduce resource accessibility. It is critical for communities to understand, plan for, and avoid climate-driven displacement.

Communities such as Flagstaff, Arizona, and Miami-Dade County, Florida, are widely reported to be experiencing climate gentrification, with many other U.S. cities speculated to become receiving communities in the near future. To address the potential adverse impacts of climate-related gentrification, it is important to recognize it when it begins to occur and understand the mechanisms that drive it. Some gentrification indicators include changing racial and ethnic compositions of neighborhoods, increasing household incomes, increasing levels of educational attainment, declining or stagnant public and subsidized housing stock, and rising rates of evictions and foreclosures.

Local governments and private interests must prioritize development that is inclusive and equitable, create capacity for new residents, and be prepared to reconcile the interests of newcomers with those of long-term residents.

To mitigate these adverse effects, the Urban Land Institute poses six broad strategies for planners, government officials, and developers to achieve more equitable outcomes in communities that are, or are anticipated to be, impacted:

- Facilitate climate-conscious local capacity building to ensure all members of a community, including the poorest and most disadvantaged, thrive. Capacity building programs might include skills development initiatives. It is important to note, however, that the burden of adapting to change should not be placed solely on the shoulders of impacted community members, with this strategy representing just one of many ways to assist community members.

- Enhance neighborhood stability through pathways to ownership. For example, programs such as community land trusts and policies supporting tenant rights of first refusal can ensure current residents of receiving communities are able to secure ownership of real property and are shielded from forthcoming rising rent and cost of living.

- Preserve and expand the availability of resilient, unsubsidized affordable housing through regulatory and programmatic interventions such as zoning code updates, housing trust funds, and community benefits agreements. These tools – including inclusionary zoning, upzoning, and resilient zoning – can harness market resources, provide flexible funding, and increase development capacity. This in turn aligns projects with community interests and mitigates climate risks, ensuring housing affordability, social equity, and environmental sustainability.

- Designate space that is accessible, affordable, and relevant through community engagement, inclusive design practices, and shared community resources that support resilience. Effective community engagement can spur critical dialogue between developers, public officials, and community stakeholders from the outset of the planning and design process. This engagement provides an opportunity for community members to learn, participate, and influence public decisions, fostering trust and local leadership development.

- Apply building design standards that promote energy efficiency and contribute positively to the health and well-being of tenants. While carbon emissions reduction is a key component of mitigating climate-related impacts in the long term, improving building performance and resilience yields immediate benefits to occupants through improved health, safety, and wellness.

- Support retrofit, maintenance, and recovery by leveraging available grant funding, creative financing mechanisms, and streamlining of administrative processes. Actions such as enabling Property Assessed Clean Energy (PACE) Financing programs, taking advantage of federal, state, and local grants for disaster recovery and resilience, and offering flexibility to individuals in local administrative processes can improve overall community resilience and protect vulnerable groups within communities.

Urban development professionals and designers still have a lot of work to do to understand the emerging dynamics of climate migration. However, there’s an opportunity for local governments and the real estate sector to take the lead, as they are uniquely positioned to understand and address attendant issues like climate gentrification. Together with communities, they can pave the way for inclusive and equitable development that prioritizes the needs of every resident. We need to act now to create a better future for all.

Lindsay Brugger is Vice President of Urban Resilience at the Urban Land Institute. Lian Plass is Senior Manager of Urban Resilience at the Urban Land Institute.

Maui's Vacation Rental Debate Turns Ugly

Verbal attacks, misinformation campaigns and fistfights plague a high-stakes debate to convert thousands of vacation rentals into long-term housing.

Planetizen Federal Action Tracker

A weekly monitor of how Trump’s orders and actions are impacting planners and planning in America.

San Francisco Suspends Traffic Calming Amidst Record Deaths

Citing “a challenging fiscal landscape,” the city will cease the program on the heels of 42 traffic deaths, including 24 pedestrians.

Defunct Pittsburgh Power Plant to Become Residential Tower

A decommissioned steam heat plant will be redeveloped into almost 100 affordable housing units.

Trump Prompts Restructuring of Transportation Research Board in “Unprecedented Overreach”

The TRB has eliminated more than half of its committees including those focused on climate, equity, and cities.

Amtrak Rolls Out New Orleans to Alabama “Mardi Gras” Train

The new service will operate morning and evening departures between Mobile and New Orleans.

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.

Heyer Gruel & Associates PA

JM Goldson LLC

Custer County Colorado

City of Camden Redevelopment Agency

City of Astoria

Transportation Research & Education Center (TREC) at Portland State University

Jefferson Parish Government

Camden Redevelopment Agency

City of Claremont