From designing streets to designing process.

When restaurant owner Mike Thompson tried to set up an outdoor dining kiosk at his business in Astoria, Queens this summer, he ran into a challenge. His restaurant did not have enough space in the street to accommodate all of his customers. Pedestrians crowded the sidewalk outside his business, sometimes flaunting social distancing requirements. Facing the uncertain future of his business, Mike joined forces with other restaurant owners on Ditmars Boulevard and came up with a plan to temporarily close two blocks over the weekends. To get the plan rolling, the group gathered support from elected officials and coordinated with the New York City's transportation department, fire chief, and transit agency to create more breathing room for both the businesses and residents of Astoria. With an application to the Open Streets: Restaurants program, the group's ground-up community initiative came to fruition, signaling a successful collaboration between city agencies, elected officials, and local stakeholders to quickly adapt to community needs during the pandemic.

Before the pandemic, Mike's efforts might have fared quite differently. His group would undoubtedly have been beleaguered by community concerns about traffic, waste, and noise. Businesses, including restaurants like his, might have been wary of losing parking spaces. The restaurant group would likely have tired of the bureaucratic process, or been warned against embarking on an ambitious effort by elected officials who have seen such efforts go awry in the past.

Prior to 2020, New York City had a total of 25 "parklets" (curbside seating areas) scattered across its five boroughs. Since it rolled out the Open Restaurants program in May, that number has risen to 10,343 and counting, with over 5,000 restaurants using the curb for seating. For New Yorkers accustomed to lengthy approval processes, extensive public meetings, and hefty permitting fees, the rapid appearance of "open streets" and "open restaurants" has been revelatory, opening New Yorkers' eyes to the potential for rapid street transformation as an economic lifeline.

To achieve this almost-instantaneous change (at least on the typical government timeline), residents and small businesses have quickly emerged as essential partners in the city's social and economic recovery, assuming roles typically reserved for business improvement districts, neighborhood associations, and community boards. New York City's Department Of Transportation, meanwhile, almost overnight condensed what had been a convoluted, seven-month approval process into one simple online form, the economic and societal benefits of which are only beginning to come into focus. For both ordinary residents and long-time policymakers, the sudden curbside revolution has prompted two important questions: 1) Did the old process need to take so long in the first place? and 2) How can we learn from this unique civic experiment to more comprehensively reimagine our streets and mobility networks beyond outdoor dining?

Aiming Higher

Over the past two decades, cities have recognized the critical role that streets play in achieving their broader policy goals. A new generation of transportation leaders has laid out ambitious plans and policies to help their citizens move around more safely, efficiently, equitably, and sustainably while reimagining streets as their largest public space. Name a challenge that society faces—climate change, equity and racial justice, a cleaner environment, safer and healthier communities, a stronger economy—and streets and mobility stand at the heart of many of the solutions.

Despite this ambition, even before COVID-19 struck, many cities were making only halting progress towards achieving their stated goals. "Vision Zero" targets adopted to eliminate traffic fatalities—a laudable objective—have only incrementally curbed traffic crashes and deaths. Many communities have set climate action goals such as reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 80% or going carbon neutral by 2050, yet most remain far from reaching those milestones. New York City's plan calls for 80% of trips to be made by transit, walking, and biking, as opposed to 67% made by those modes today. But in most cities, including New York, transit use has stagnated and bicycling mode share remains in the low single digits. At the same time, tech companies have used aggressive consumer-oriented growth strategies to shift the mobility paradigm into the future, often in direct conflict with city officials and standard processes.

The 2020 experience has underscored the reality that dramatic, widespread, and fast change is needed to move the needle: to make other options safer, more convenient, and comfortable enough to be viable alternatives for trips that people currently make by car. The incremental progress that cities have made over the past decades in creating bus lanes, bike lanes, and more public space represents significant progress, but when it comes to outcomes, cities need to be reaching for a higher standard of success at a much faster pace.

One need only look at cities around the world for examples of large-scale change, where bold, imaginative efforts to discourage inefficient, unsustainable transportation modes, expand affordable, healthy multi-modal options, and create revenue sources to pay for it all do yield results. Milan turned more than 35 kilometers of streets over to cyclists and pedestrians, including an ambitious system of temporary bikeways. "Corona cycleways" and pedestrian zones have suddenly appeared in cities from Paris to Bogotá to Brussels, while London's Streetspace program is rapidly redesigning streets to accommodate up to five times more people walking and ten times more people bicycling, with an eye toward making many of the changes permanent.

'Never Waste a Good Crisis'?

For cities around the world, the pandemic created the space to accelerate ambitious goals and programs for transforming city streets. The idea that you should "never waste a good crisis" has spread from mayors' offices to policymakers and advocates, who rightly see this moment as both a strategic opportunity for change and a crystal clear alignment between street transformation and economic success. Cities mobilized to make change happen fast, instituting self-certification processes that upended the traditional mechanisms of city approvals and permits.

While cities should be applauded for quickly developing and implementing strategies to reduce the economic and health impacts of the pandemic—oftentimes going well outside of their typical comfort zone—some critics contend that these efforts cater to the interests of the well-to-do and are being pursued at the expense of real public health and economic challenges faced by low-income and minority communities. At a time when the United States is reckoning with entrenched racial divides and persistent protests against police brutality, the street has emerged as another flashpoint in the culture war and an expression of both civic priorities and civic neglect. A widely distributed photograph from Cincinnati has come to epitomize this emerging divide: Are we redesigning our cities for brunch while displacement and disease engulf our most vulnerable neighborhoods?

Despite the many positive aspects of open streets and restaurants, the quick-build response revealed a fault line between those who see the transformation of city streets as a driver of positive economic recovery and others who see it as an insufficient and superficial response to the inadequate services, disinvestment, and overt racism that neighborhoods have endured.

As these changes rolled out, many cities lacked an overarching vision for how these "spot" changes would fit into a long-term plan for their transportation network. Many underestimated how long the crisis would drag on and are now trying to translate a patchwork of quick-build projects into a comprehensive strategy for the city's future. Some, like Seattle, are now beginning to ask the critical questions that they glossed over as pressure loomed in the spring. Should some open streets be permanent? How do open restaurants fit into overall priorities for valuable curbside real estate, and which ones still make sense when indoor dining resumes? Could some streets and curb space be better used for other things like loading zones, bioswales, shade, seating, bus lanes, or bike and bikeshare parking? How can we engage more communities in the process and reallocate resources to ensure that volunteer-based programs don't just benefit wealthier areas? How can streets be used for more than recreation, especially in areas where distrust of government and police are entrenched?

Cities must confront all of these questions, striking a delicate (and often elusive) balance between planning comprehensively and getting things done quickly. While the task may seem daunting, the good news is that these two challenges offer cities an opportunity to course-correct and create a vision for lasting change that is both more inclusive and transformative—rising to the level of our 21st century challenges.

Envisioning the City Network

What shape might that more ambitious vision take?

In a nutshell, it means establishing priority networks for transit, biking, walking, public space, and freight. You can't improve a transportation system in an impactful, coordinated way if you don't know what you're working towards—a vision of the interconnected overall system that your city needs now and into the future. Such overall frameworks help cities and their communities stay focused on options that help achieve the citywide vision while also being tailored to support each neighborhood's local needs.

These plans should be "blue sky" in the sense of creating the best (e.g., safest, most direct, most convenient and comfortable) routes, and in the sense of not treating today's street design (number of driving lanes, the existence of parking) as the starting point. Most importantly, these plans must be ambitious enough to actually achieve the goals that cities have set around climate action, traffic safety, equity, public health, and sustainability.

In New York, the NYC Department of Transportation (DOT) and Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA)'s recent planning around the city's transit, truck, walking, and bicycling networks provides a strong foundation for that kind of plan. Additionally, New York's Streets Master Plan legislation passed by the City Council enables just this type of ambitious planning so that the city, in collaboration with its diverse neighborhoods, can develop a clear vision for how and where to prioritize bicycling, transit, and other modes within the broader network. Likewise, the Regional Plan Association (RPA) recently developed a well-researched proposal for a network of safe, convenient bicycle "highways" covering all neighborhoods of the city that, along with New York City's own "Green Wave" plan, adds on to existing concepts without reinventing the wheel.

Developing a citywide vision need not be overly complicated or time-consuming, at least for a "version 1.0" that puts the good before the perfect.

So what could this look like? Here we step through an example using Manhattan's central business district.

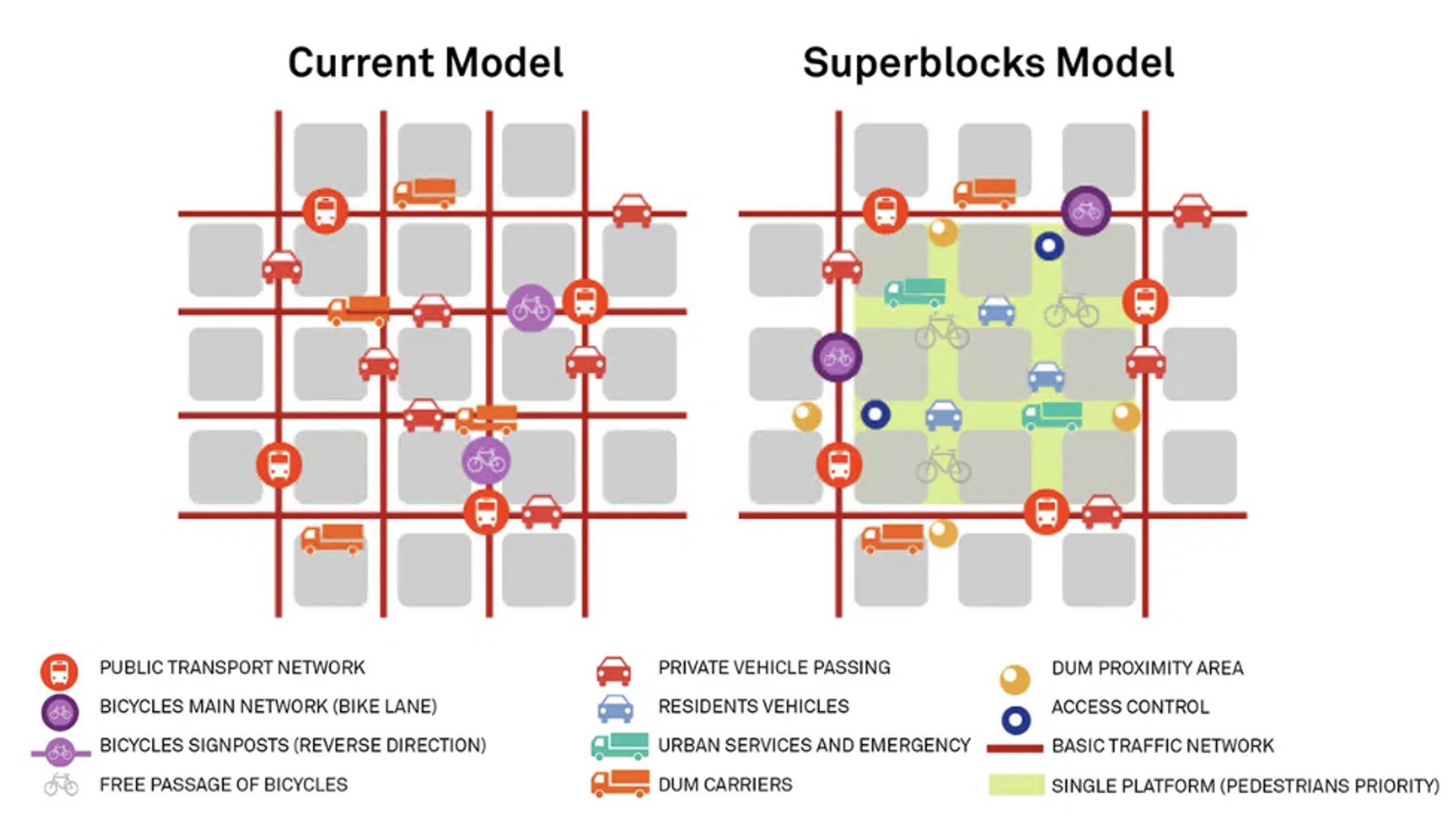

This concept is hardly new. Barcelona has embraced this ideal as part of their Superilles or Superblocks initiative, which was created by the city council with the Urban Ecology Agency. Paris, similarly, has championed the 15-minute city as a model for its transformation into a convenient, walkable, and livable city. The basic building blocks of this approach are routine traffic planning and street design in Dutch cities, which are renowned for their pedestrian friendly woonerven. Early neighborhood plans for American cities embraced similar ideals, often referred to as the Neighborhood Unit, but oriented streets around automobile access and functional classification.

Using this ideal as a base, we began applying our model to the bike, bus, and pedestrian networks of the Manhattan Core. This required a detailed analysis not only of existing and planned networks, but also of potential connections that have proven challenging for the city to complete. We also looked closely at pedestrian zones and open streets that the city has started to demarcate throughout the pandemic, using those and other inputs to inform a larger pedestrianization strategy for the island of Manhattan.

Collectively, our work created an ideal network map for the core that not only creates greater access to protected and dedicated infrastructure for bikes and buses but also rethinks the fundamental relationship between "internal" facing side streets (which prioritize pedestrians) and perimeter streets that focus more on circulation and mobility.

Empowering Neighborhoods

If the pandemic has taught cities one lesson, it is their extraordinary power to enable trends of widespread, community-driven transformation. There is perhaps no better or more visible illustration of this in New York than the city's curbside dining program. Its success even energized the city's mayor, who has generally been averse to reducing parking but recently called for the program to be extended in perpetuity as a new summer tradition.

What can we learn from this experiment, and what is worth making permanent—both in terms of infrastructure and in terms of process? The issue, simply put, is not that city transportation departments are overly bureaucratic, though many have that reputation; it's that many city agencies have created such complex, stakeholder-intensive approval processes that they are essentially self-defeating. The timeline for transformation alienates both the leaders who aspire to see change happen quickly and the communities who don't have the resources to commit to a drawn-out process. The result, in many places, has been that well-organized business improvement districts and organizations in business districts or wealthier neighborhoods with the resources to stomach a seven-month (or seven-year) process take advantage of these programs, while outlying and resource-constrained communities don't buy in.

With basic, clear-cut guidelines, a few hundred (or thousand) dollars, and perhaps a creative contractor, any neighborhood can transform their street. Now that cities know that and have seen it happen firsthand—over 5,000 times in New York City alone—where do city officials go from here? How can the top-down and the bottom-up come together to quickly make change happen and leverage our streets to enhance our society?

First, cities should adopt street transformation processes that energize individual entrepreneurship and create shared stewardship of the public realm without giving public spaces over to private interests. Of course, what sounds nice in theory can be difficult in practice. For years, cities and community organizations have battled developers trying to privatize or limit access to privately owned public spaces (POPS). Once the dust settles, how will cities balance the interests of a restaurant over those of the larger community? What determines whether curbside seating is a better use of space than a bike lane or a bioswale, projects that are part of interconnected systems rather than just serving adjacent businesses?

Second, city officials need to start better tracking the distribution of resources across neighborhoods to diagnose why some neighborhoods are seeing more investment and engagement than others, breaking the cycle of relying on rezoning and development as a precursor for infrastructure funding, a practice which only exacerbates cultural, racial, and economic divisions.

Lastly, non-profit organizations with the know-how to implement and manage these processes can play a significant role in bringing knowledge and expertise to areas that lack the capital and/or governing structure to lead engagement processes. For example, "Peer Neighborhoods" initiatives, in which experienced BIDs mentor local leaders in disadvantaged neighborhoods and provide them with tools to manage public realm programs, promote a shared understanding and approach to successful place management and project implementation.

A positive example of collaboration between the not-for-profit world and the city to empower neighborhoods is the Neighborhood Plaza Program (NPP), created as part of the city's OneNYC Plaza Equity Program and run by the Horticultural Society of New York (the "Hort"). The Hort works closely with local partners in underserved neighborhoods to provide necessary tools to build and grow relationships with local businesses, host cultural events, and build support for clean, green public spaces. Currently limited to only 14 pedestrian plazas, there is tremendous room to scale this model up.

Whether the surge of open restaurants and recreational open streets popping up in cities is indicative of how cities have failed disadvantaged communities is an important question. It comes with a corollary: can cities open up and re-orient these newly streamlined processes and models to support the full spectrum of communities and goals—with a focus on those who need the most help and have had the least voice—by building capacity and harnessing the homegrown ideas in each neighborhood?

Cities must focus on designing creative processes, not just innovative streets. For too long, the emphasis has been on developing one great project at a time, with the assumption that the one will lead to the many. But anyone who has walked down the streets of their city can see that this model of change hasn't led to broader transformative outcomes and that change is as much about creating space for individual and community initiative as it is about creating far-reaching projects and programs.

David Vega-Barachowitz is Director of Urban Design at WXY Architecture + Urban Design. As a city planner and urban designer, David's work explores the instrumentality of codes in shaping the built environment. His practice focuses on the development of new tools, research methods, and design perspectives that investigate and challenge the DNA of cities, from zoning and building codes to street and engineering manuals. David has spearheaded a range of projects and initiatives, including the development of neighborhood-based public realm plans, research on new and emerging mobility options, and guidelines for the design and retrofit of public housing complexes. He is a former Senior Urban Designer at the New York City Department of City Planning and the first director of the Designing Cities Initiative at the National Association of City Transportation Officials (NACTO), where he spearheaded the production of NACTO's Urban Street Design Guide (Island Press, 2013) and Urban Bikeway Design Guide (Island Press, 2012). David is co-author of Start-up City: Inspiring Private and Public Entrepreneurship, Getting Projects Done, and Having Fun (Island Press, 2015), which he wrote with Gabe Klein. He holds a Master of City Planning from MIT and a bachelor's degree in Urban Studies with Architecture from Columbia University.

Mike Flynnis a nationally recognized leader in urban mobility. Growing out of his background in social and environmental advocacy, he has devoted the past 20 years to helping cities envision and implement better transportation systems that support broader goals around equity, economic development, climate action, and community resilience. At Sam Schwartz, Mike leads the firm's integrated planning work, with the team's award-winning work spanning multi-modal transportation plans and designs at all scales; data analysis, modeling, and visualization; resilience, recovery, and sustainability planning; policy and planning for emerging mobility technologies and services; and strategic communications, community engagement, and workshop facilitation. Mike is active in developing and sharing best practices in the industry through organizations such as the Transportation Research Board, American Planning Association, and Institute of Transportation Engineers, and as an educator and trainer.

Lian Farhiis an urban planner and designer who explores the interrelationships between public realm, urban mobility and placemaking. She possesses a multidisciplinary background and ten years of experience practicing architecture, urban design and multi-modal transportation planning in the private and public sectors. Lian has designed, implemented, and managed a range of real-world projects to create safe, livable, and future-ready streets, and has conducted quality-of-life studies to quantify the benefits of public realm improvements on community health, safety, and economic vitality. She has broad experience in developing vision plans, design guidelines and robust outreach and community engagement processes. At Sam Schwartz, she leads complete streets projects focusing on pedestrian and micromobility circulation, public realm vision plans and sustainable mobility research. Lian also has international experience in transportation planning working on the design of Tel Aviv's mass transit system and conducting research in Europe for NTA.

This article also featured graphic contributions by Manasi Punde, architectural designer at WXY architecture + urban design.

Maui's Vacation Rental Debate Turns Ugly

Verbal attacks, misinformation campaigns and fistfights plague a high-stakes debate to convert thousands of vacation rentals into long-term housing.

Planetizen Federal Action Tracker

A weekly monitor of how Trump’s orders and actions are impacting planners and planning in America.

Chicago’s Ghost Rails

Just beneath the surface of the modern city lie the remnants of its expansive early 20th-century streetcar system.

Bend, Oregon Zoning Reforms Prioritize Small-Scale Housing

The city altered its zoning code to allow multi-family housing and eliminated parking mandates citywide.

Amtrak Cutting Jobs, Funding to High-Speed Rail

The agency plans to cut 10 percent of its workforce and has confirmed it will not fund new high-speed rail projects.

LA Denies Basic Services to Unhoused Residents

The city has repeatedly failed to respond to requests for trash pickup at encampment sites, and eliminated a program that provided mobile showers and toilets.

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.

planning NEXT

Appalachian Highlands Housing Partners

Mpact (founded as Rail~Volution)

City of Camden Redevelopment Agency

City of Astoria

City of Portland

City of Laramie