A case of mistaken identity has embroiled California in election controversy, as claims of bias and misinformation swirl around Prop 13 (2020), Prop 13 (1978), and an anticipated "split roll" initiative.

Dear California voters: The Prop 13 on the statewide ballot in March isn't the Prop 13 reform everyone's talking about on social media.

There is a legislative initiative on the statewide ballot this March that goes by the name of Prop 13 (full title: "Authorizes Bonds for Facility Repair, Contraction, and Modernization at Public Preschools, K-12 Schools, Community Colleges, and Universities"), but it should not be confused with the "California Schools and Local Communities Funding Act of 2019." The latter would enact fundamental reforms of the state's property tax laws, as implemented by the state in 1978 with the much more infamous, historic version of Prop 13. But the "California Schools and Local Communities Funding Act of 2019" is still collecting the signatures necessary to qualify for a later statewide election, and voters won't be deciding to reform or repeal the historic version of Prop 13 this March.

For the sake of both writer and reader, the remainder of this article will refer to the March 2020 ballot initiative as Prop 13 (2020), and the historic ballot initiative as Prop 13 (1978). The "California Schools and Local Communities Funding Act of 2019," which has not been designated with a proposition number, will be referred to as the "California Schools and Local Communities Funding Act of 2019."

If eventually approved for the ballot, the "California Schools and Local Communities Funding Act of 2019" would offer voters the chance to implement a "split roll." The split roll would fundamentally alter the state's property tax laws, as determined by Prop 13 (1978), approved by voters as a landmark component of the infamous "Tax Revolt" of the 1970s. Prop 13 (1978) set limits on property tax increases throughout the state, forever altered the fiscal direction of the state, and entered the history books as easily one of the most infamous and controversial ballot propositions ever approved in California. The split roll proposed by the "California Schools and Local Communities Funding Act of 2019" would, if it gathers enough signatures for the ballot and is then approved by voters, remove limits on increases to commercial property taxes while leaving in place limits on property tax increases for residential homeowners.

The property tax limits implemented by Prop 13 (1978) are immensely popular in the state of California, serving as a model for other states and contributing greatly to the controlling interests of property owners in local politics. Ending the Prop 13 (1978) property tax limits for residential homeowners is widely considered a political third rail in California. The prospects of a full repeal of Prop 13 on any short-term timeline are essentially nil.

State of Confusion

Some of the confusion about whether California voters will be voting on Prop 13 (1978) reform this year can be rightfully traced to a decision by proponents of the "California Schools and Local Communities Funding Act of 2019" to scrap an earlier version of the initiative, after collecting enough signatures to qualify for the November 2020 statewide ballot. That earlier version of the "California Schools and Local Communities Funding Act of 2019" set off alarms for Prop 13 (1978) protectionists—so much so that they are now mistaking an education bond for a split roll.

The Democratic leadership in California is also partly responsible for the state of confusion about Prop 13 (1978) reform. Opponents of the split roll and numerous editorial boards across the state have called out State Attorney General Xavier Becerra for the official language used to describe the "California Schools and Local Communities Funding Act of 2019" as it circulates for signatures. The full title of the previous version of the initiative read as follows: "Requires Certain Commercial and Industrial Real Property to be Taxed Based on Fair-Market Value. Dedicates Portion of Any Increased Revenue to Education and Local Services." The full title of the new version, currently collecting signatures, reads as follows: "Increases Funding for Public Schools, Community Colleges, and Local Government Services by Changing Tax Assessment of Commercial and Industrial Property."

Whether that difference of wording is worthy of vitriolic editorials by the Orange County Register and the Daily Breeze is questionable, but the official framing of the initiative's purpose has undoubtedly introduced skepticism and fueled confusion. Prop 13 (2020) offers another example of questionable nomenclature. The Howard Jarvis Tax Association, the group behind Prop 13 (1978), called on the state to retire the Prop. 13 designation to prevent confusion. The state clearly has not headed that request.

Misinformation Spreads

Those who oppose any reforms of Prop 13 (1978) are taking misinformation several steps further than those examples of poor word choice, however. Recent, widely shared social media posts have characterized both Prop 13 (2020) and the "California Schools and Local Communities Funding Act of 2019" as an effort to repeal Prop 13 (1978). Whatever malfeasance is motivating Becerra's diction pales in comparison to this example of a thoroughly misleading post I recently discovered on Facebook, which describes Prop 13 (2020) as an "amendment" to Prop 13 (1978).

Characterizing Prop 13 (2020) as an amendment to Prop 13 (1978) is incorrect, but posts like these have been spreading quickly across social media. Politifact documented and fact checked several additional Facebook posts that describe Prop 13 (2020) as an attempt to slip a full repeal of Prop 13 (1978) under the radar. Check the replies on these posts for an idea of the effect of such misinformation on a typical voter—many who have already mailed in their ballots.

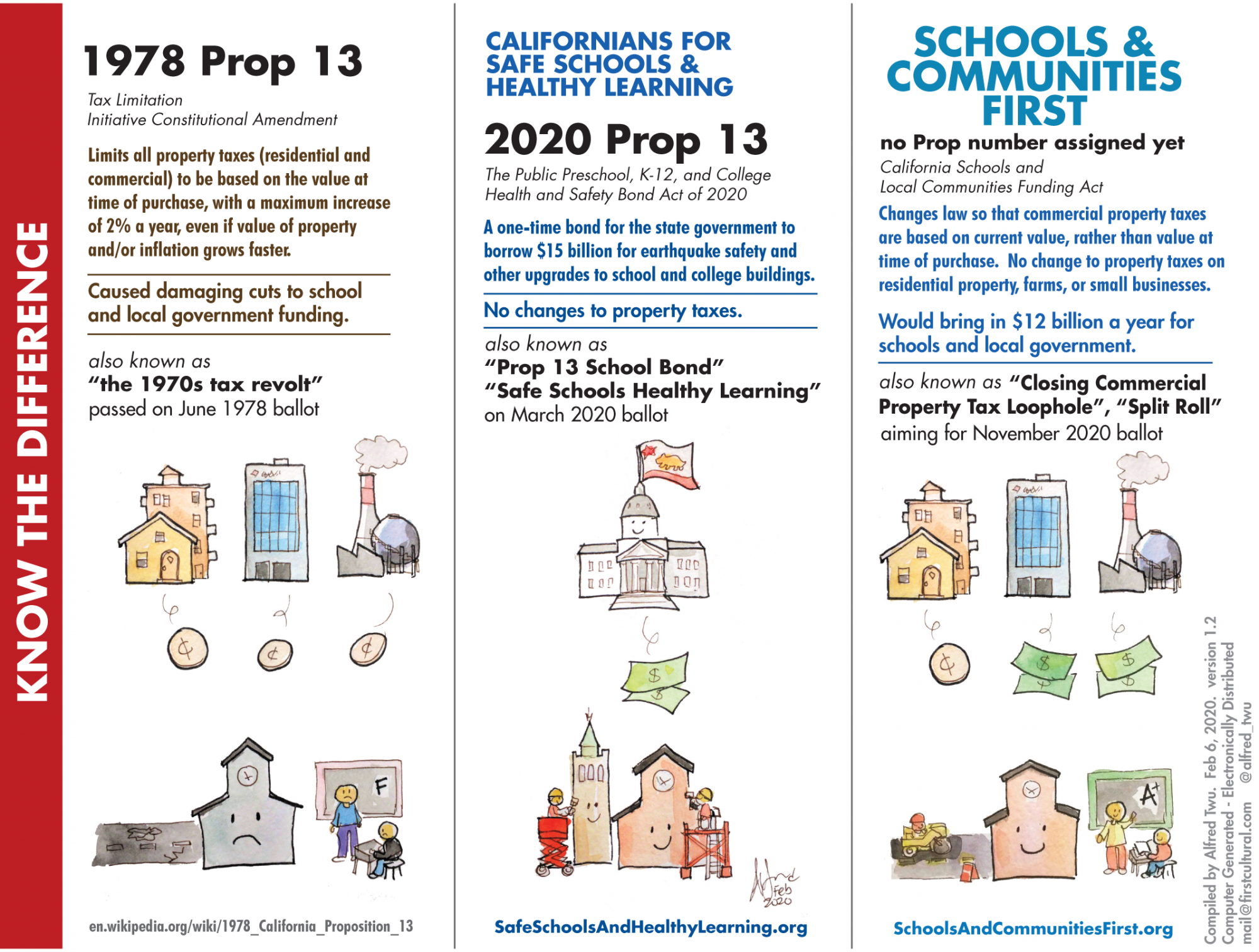

Organizations and individuals who support Prop 13 (1978) reforms have noticed the popularity of these posts, and are mobilizing to combat misinformation. Alfred Twu, who in the recent past created a widely shared infographic to explain density, created the following.

Mainstream media outlets, like Capital Public Radio and a local ABC News affiliate, have also joined the chorus in an attempt to clarify the confusion. So let's be absolutely clear: neither Prop 13 (2020) nor the "California Schools and Local Communities Funding Act of 2019" would repeal Prop 13 (1978). The "California Schools and Local Communities Funding Act of 2019" isn't on the ballot. If and when it is on the ballot, the "California Schools and Local Communities Funding Act of 2019" won't repeal property tax limits for residential property owners.

Prop 13 (2020) and Property Taxes

Another point of clarification is necessary to explain the actual connection between Prop 13 (2020) on property taxes. Opponents of Prop 13 (2020), like the Howard Jarvis Tax Association, have have pointed out that the proposed school bonds would require with financing revenue generated from local property taxes. As noted in a recent editorial by The Mercury News opposing Prop 13 (2020), the initiative is written specifically to shift the revenues necessary to finance the bonds from development fees to property taxes:

The measure, which was placed on the ballot by the Legislature, would ban school districts from charging developers fees for multi-family projects within a half mile of major bus, rail or ferry transit stops. And for all other multi-family projects, the fees would be reduced by 20%.

The language of the bill on the state's official voter guide confirms that assessment:

Specifically, school districts would be prohibited from assessing developer fees on multifamily residential developments (such as apartment complexes) located within a half-mile of a major transit stop (such as a light rail station). For all other multifamily residential developments, currently allowable developer fee levels would be reduced by 20 percent moving forward. These limitations would be in place until January 1, 2026.

While Prop 13 (1978) set limits on how much property taxes could increase as a result of rising property values, Prop 13 (1978) also allowed for voter-approved local property taxes to finance bonds for very specific kinds of projects, including school construction. As noted in a property tax paper written by the California Legislative Analysts's Office (see pages 8-9 for the desired explanation), local property taxes can increase proportionally to the financing needs of voter-approved bonds. Voter approved bonds are limited by state law to an amount proportional to the assessed value of property within the district (see "State Law Places Limits on Local Borrowing" section of the Legislative Analyst's analysis of Prop 13 (2020)) . If approved, Prop 13 (2020) could indeed raise local property taxes, but within the limits of state law. A voter-approved increase in property taxes, limited by state law, is not the same thing as a full repeal, or an amendment, of Prop 13 (1978).

Planning and the Culture War

By placing the burden of bond financing on property owners instead of developers, the authors of Prop 13 (2020) invited all the vitriolic baggage of the state's housing affordability debate into the conversation, in addition to the traditional political forces already viciously contending Prop 13. The resulting debate about the merits of Prop 13 (2020) has devolved, like with so many previous development policy discussions, into another episode of the Culture War.

When all is said and done in California's March statewide election, a substantive discussion on Prop 13 (2020)—raising questions about planning, demographics, and housing costs—could be collateral damage in this pernicious whirlwind of property politics and social media misinformation.

The confusion about Prop 13 (2020) is likely only prelude to the kind of misinformation voters will encounter if and when the "California Schools and Local Communities Funding Act of 2019" finally reaches the ballot. In news that should shock absolutely no one, the ability of social media to mislead voters is not exclusive to presidential campaigns. Misinformation campaigns like these should be expected to alter the fate of planning-related ballot measures in the future, and not just in California.

Planetizen Federal Action Tracker

A weekly monitor of how Trump’s orders and actions are impacting planners and planning in America.

Chicago’s Ghost Rails

Just beneath the surface of the modern city lie the remnants of its expansive early 20th-century streetcar system.

San Antonio and Austin are Fusing Into one Massive Megaregion

The region spanning the two central Texas cities is growing fast, posing challenges for local infrastructure and water supplies.

Since Zion's Shuttles Went Electric “The Smog is Gone”

Visitors to Zion National Park can enjoy the canyon via the nation’s first fully electric park shuttle system.

Trump Distributing DOT Safety Funds at 1/10 Rate of Biden

Funds for Safe Streets and other transportation safety and equity programs are being held up by administrative reviews and conflicts with the Trump administration’s priorities.

German Cities Subsidize Taxis for Women Amid Wave of Violence

Free or low-cost taxi rides can help women navigate cities more safely, but critics say the programs don't address the root causes of violence against women.

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.

planning NEXT

Appalachian Highlands Housing Partners

Mpact (founded as Rail~Volution)

City of Camden Redevelopment Agency

City of Astoria

City of Portland

City of Laramie