An exhibit by Congolese artist Bodys Isek Kingelez at the Museum of Modern Art invokes urban idealism at the same time that it serves as a foil for poverty and deprivation in the megacities of the developing world.

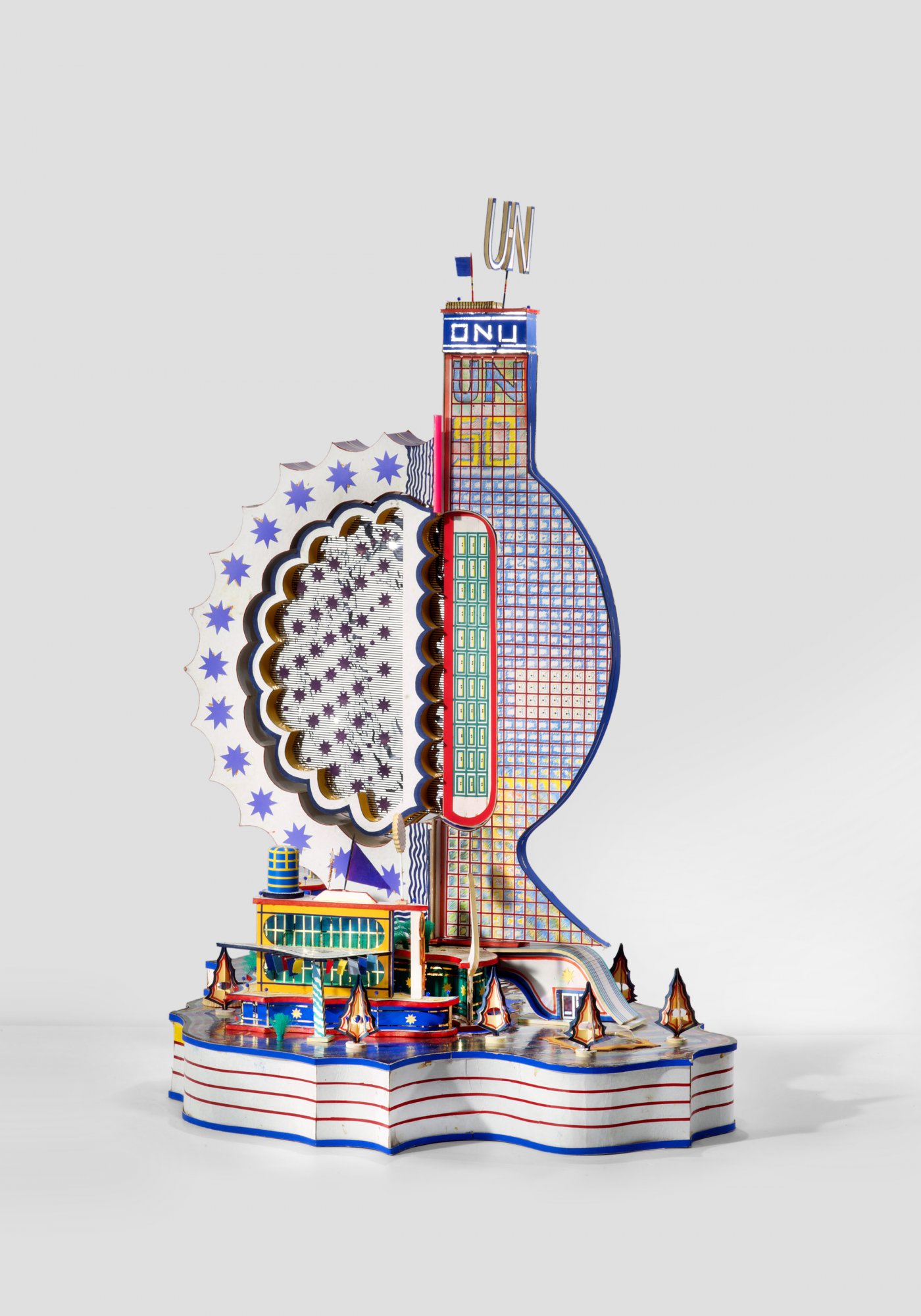

The two-dozen or so bright, garish, playful, unlikely, and intricately detailed models of buildings and cities on display in the City Dreams exhibit at the Museum of Modern Art look astonishingly like a collaboration between Le Corbusier and Pee-wee Herman.

Their creator, however, was neither an austere, imperious Modernist from Switzerland nor a fictional man-child from Florida. He is Bodys Isek Kingelez, a self-taught sculptor who responded to war and dictatorial strife in Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of Congo) with an imagination fueled by equal parts whimsy, defiance, and hope.

Kingelez's consructions largely separate design from architecture. The two-dozen or so pieces in City Dreams are not models of buildings he would or could build but rather are fully realized artworks that allude to the real world while simultaneously existing in a fantasy realm all their own. Using everything from paper, plastic, and foamcore to aluminum foil, rubber bands, and toothpicks—to name just a few of the roughly 50 materials listed in the exhibit catalog—Kingelez imagines multicolored towers, spires, cornices, pediments, and just about any other bit of postmodern ornamentation you can imagine, affixed with an endearingly amateur hand. Corbusier would have a heart attack.

The exhibit includes both discrete buildings and entire cityscapes, the latter roughly the size of a bedroom model train set, that all reflect decidedly Modernist principles. Buildings are separated from each other. Streets are wide and prominent. Plazas and other open space are available to nonexistent pedestrians. Residents travel by monorail and elevated highway. Skylines are topped by monumental towers that serve little purpose other than to parody their infinitely more purposeless real-world counterparts. Signage abounds—often cheekily advertising Kingelez's own name. His "dream" looks nothing like the dense, walkable, endearing places that many planners promote today.

While Kingelez's aesthetic may be child-like and therefore timeless, he is very much a product of his time and place. Many of his constructions refer to Kinshasa, the capital of the DRC and, today, one of the booming cities of Africa. That boom would have been well underway when Kingelez was active, primarily in the 1980s and 1990s, at the end of the reign of dictator and kleptocrat Mobutu Sese Seko. Kinshasa grew from 2.6 million in 1984 to over 11 million today. It surely was not pretty.

For all of Kingelez's whimsy, his creations convey earnest political messages. One building is a hospital for AIDS patients, a nod to the crisis that escalated in part because of governmental neglect. Another is a headquarters for the United Nations. More darkly, Kingelez's work speaks to the anxiety of living under dictatorship. Whatever freedom he may have felt in his workshop was likely absent on the real streets of Kinshasa. The Congolese government's failure to promote humane, democratic development spurred Kingelez to literally take matters into his own hands. When government and commerce cannot provide, art must step in.

Ville Fantome (1996), whose title coincidentally invokes Le Corbusier's Villa Radieuse, was meant to represent “a peaceful city where everybody is free,” Kingelez said. "It's a city that breathes nothing but joy, the beauty of life. It's a melting pot of all races in the world. Here you live in a paradise, just like heaven." That's quite a burden for a collection of foamcore and cardboard.

The Modernist elements of his designs—ones that are often associated more with authoritarianism than freedom—may simply have been a reflection of the times, as Kingelez responded to the chaos and dysfunction of late 20th century African cities the same way that the Modernists did to American and European cities in the early half of the century. Kingelez's vision echoes that of Afrofuturism, the 1970s movement that envisioned a modern, prosperous postcolonial Africa. His designs are not entirely dissimilar to that of the movie Black Panther's fictional Wakanda, which explores similar political and aesthetic themes.

As fanciful as Kingelez's creations are, reality has caught up with them in the three decades since he did his major work.

While New York City's new generation of supernal skyscrapers, many of which are clustered around MoMA, are relatively demure, the skylines of many new cities bristle with exactly the type of ornament that Kingelez envisioned, if not the social harmony for which he hoped. Think of Shanghai, Shenzhen, Baku, Doha, and, of course, Dubai. Contemporary design and engineering techniques have made feasible many design elements that previously might have been impossible or prohibitively expensive. Changing tastes have made them desirable. And, in many cases, autocracy has made them permissible.

Kingelez's works implicitly protest authoritarianism and poverty in his home country. Today's fantastical buildings celebrate authoritarianism and wealth in theirs. Meanwhile, cities in Africa continue to grow with explosive speed. Many such cities have pockets of wealth surrounded by ever expanding slums. Their impoverished majorities, numbering now in the hundreds of millions across Africa, who seek fun or utopianism may have to use their imaginations.

Bodys Isek Kingelez: City Dreams

Through January 1, 2019

The Museum of Modern Art

New York City

Planetizen Federal Action Tracker

A weekly monitor of how Trump’s orders and actions are impacting planners and planning in America.

San Francisco's School District Spent $105M To Build Affordable Housing for Teachers — And That's Just the Beginning

SFUSD joins a growing list of school districts using their land holdings to address housing affordability challenges faced by their own employees.

The Tiny, Adorable $7,000 Car Turning Japan Onto EVs

The single seat Mibot charges from a regular plug as quickly as an iPad, and is about half the price of an average EV.

Engineers Gave America's Roads an Almost Failing Grade — Why Aren't We Fixing Them?

With over a trillion dollars spent on roads that are still falling apart, advocates propose a new “fix it first” philosophy.

The European Cities That Love E-Scooters — And Those That Don’t

Where they're working, where they're banned, and where they're just as annoying the tourists that use them.

Map: Where Senate Republicans Want to Sell Your Public Lands

For public land advocates, the Senate Republicans’ proposal to sell millions of acres of public land in the West is “the biggest fight of their careers.”

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.

Borough of Carlisle

Smith Gee Studio

City of Camden Redevelopment Agency

City of Astoria

Transportation Research & Education Center (TREC) at Portland State University

City of Camden Redevelopment Agency

Municipality of Princeton (NJ)