A case study of Vallejo shows how the city is continuing revitalization efforts without the powerful tools provided by its former redevelopment agency.

Until Governor Jerry Brown signed legislation eliminating California's redevelopment agencies (RDAs) in 2012, developers had committed to big projects in the declining downtown and underused waterfront of the city of Vallejo. The commitments depended on its Vallejo Redevelopment Agency assembling and clearing sites, developing necessary infrastructure, and covering initial costs with tax increment financing.

Municipalities use the increase in tax revenues [pdf] generated by new development, otherwise known as tax increment financing (TIF), to repay the bonds issued to finance the development.

Why the attention to post redevelopment agency efforts of this small city of 118,078, located on the bay 35 miles northeast of San Francisco?

Vallejo evidences the civic involvement described by James Fallows in The Atlantic article, "How America Is Putting Itself Back Together" that is important to a sense of place and vitality in America's second tier cities. As James and Deborah Fallows explored the nation in their single-engine airplane, they discovered much about "American reinvention and renewal." He writes: "Many people are discouraged by what they hear and read about America, but the closer they are to the action at home, the better they like what they see." Thus, Fallows suggests eleven signs that a city will succeed, including local patriots, public-private partnerships, a civic story, a downtown, openness to new Americans, a cared-about community college, big plans, and, what he considers a most reliable sign, a craft brewery. Vallejo evidences many of these attributes, including big plans for reinvention and renewal.

Until 2012, the Vallejo Redevelopment Agency (RDA) provided mechanisms for funding large-scale efforts of a city facing economic challenges. Its Mare Island Naval Shipyard closed in 1996, eliminating over one third of local jobs. The Great Recession of 2008 caused business closures; record numbers of home foreclosures; and Chapter 9 bankruptcy, from May 2008 to November 2011. The 2014 Napa earthquake damaged many of the historic buildings in the downtown.

In 2002, the city and its redevelopment agency began working with Triad Communities LP toward creating a mixed-use development with high density housing on surface parking lots owned by the city and the RDA. A Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) was based on an award winning 2005 Downtown Specific Plan covering 97.2 total acres. Triad and the city shared the cost of preparing this vision plan, with Triad paying two-thirds and the city paying one-third.

The primary focus of the Downtown Vallejo Specific Plan is "to introduce high density mixed-use housing while revitalizing existing retail and commercial areas." The specific plan's chapter on implementation acknowledges that financing public improvements requires public private partnerships between the city, the redevelopment agency, property owners, and developers. The tax increments created by development would be one among several sources of funding. The MOU was intended to be the framework for a Disposition and Development agreement for what were considered "catalyst sites," consisting of seven parcels, totaling 8.4 acres.

There would be two phases of development to include approximately 800 for-sale and rental housing units, 18,300 square feet of live-work space, and 75,000 square feet of retail, office, and commercial space. The condominium and rental apartments would meet the needs of households for whom Vallejo’s primarily detached housing stock is less suitable.

The vision was not realized, but two smaller accomplishments are exemplars of Vallejo's potential. The historic Empress Theatre opened as a vaudeville house in 1911. Damaged in the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake, it had been dark for 20 years when Triad bought and began restoring it in 2006 in partnership with the city and the Vallejo Community Arts Foundation (VCAF). The Downtown Specific Plan considers the Empress Theatre as a key element in the restoration of downtown. VCAF now manages the theater as a live music, dance, and film venue.

The Temple Art Lofts provide another success story for the city's RDA. Domus Development, specializing in affordable housing and infill mixed-use projects, partnered with the city and the RDA to buy two foreclosed buildings, using a combination of funding sources, including from the federal Neighborhood Stabilization Program (NSP) designed to soften the effects of the foreclosure crisis. Vallejo's former Masonic Lodge, a distinguished 1917 Classical Revival building, along with an adjacent, two-story Italianate building dating from 1874, have been restored after having stood vacant and suffering damage by weather and vandals. The buildings now serve as 29 affordable live/work apartments for artists and include separate studio space, a performance hall, and street-level retail space.

Temple Arts Lofts images courtesy of Domus Development.

Vallejo's waterfront also has underused and developable land that is being used for surface parking.

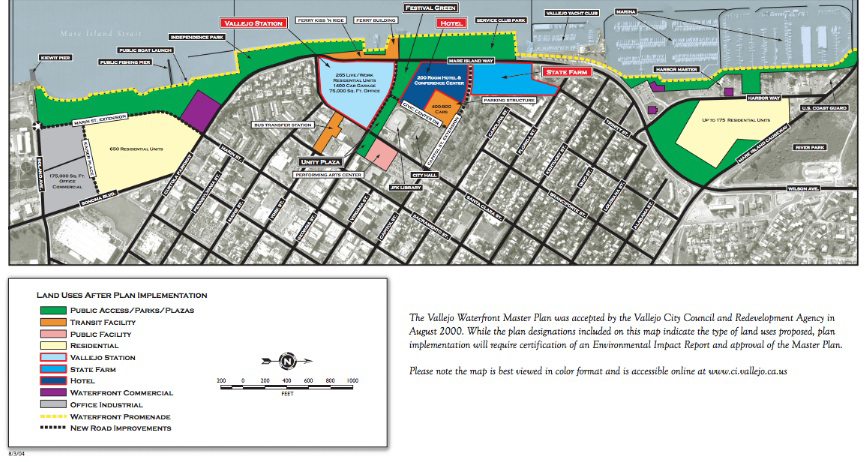

The city and Callahan/DeSilva Vallejo, LLC prepared a Waterfront Planned Development Master Plan covering approximately 92 acres that included 35 acres devoted to public uses including a public parking garage for ferry parking and a multi-modal transit center. The plan includes 28 acres for parks, open spaces, plazas, and promenades. Mixed commercial and housing uses would include approximately 562,000 square feet of retail/commercial/office space and 1,080 units of housing.

The waterfront plan is still being pursued with the city's Economic Development Department overseeing the relationship with the developer. RDA obligations have shifted to the developer, which affects the market feasibility of the project. Alea Gage, the city planner leading the project, acknowledges that the end of the RDA altered the underlying financial premises; reassessing the price and terms of the project has led to an updated Disposition and Development Agreement (DDA) with Callahan. The City Council is currently considering this fifth DDA. Of the three major waterfront parcels, the northern and central portions are slated for mixed-use residential, retail, office, and commercial; visitor-serving uses; a 10,000 square foot transit center; and open space along the water. The southern portion was removed from the DDA and remains with the successor agency to the former redevelopment agency while PG&E cleans the site of contaminants resulting from its former use.

The waterfront development infrastructure was completed by the city in the depths of the recession and is an accomplishment for the city. Phase A of the development of a parking garage provided 750 spaces; Phase B, anticipated to provide at least 550 spaces, is being implemented.

Without the redevelopment agency and TIF, Vallejo is struggling to replace the funding mechanisms that attracted developers to big projects. As Annette Taylor, the city planner involved in the downtown specific plan put it, "The well ran dry." An example of the consequences is suggested by Reporter Carolyn Said in a November 9, 2013 SFGate story, "Vallejo sees influx of artists from pricier areas," citing Dan Keen, Vallejo city manager, who says, "Vallejo's downtown clearly is still struggling. Its antique stores, secondhand shops and cafes don't attract the same volume of customers, as would a grocery store or drugstore. Downtown is an area looking for a new identity." The middle-income residents attracted by the Triad development would bring the dollars needed to support downtown businesses.

The continuing efforts of Vallejo planners exemplify the resilience of cities and of the civic-minded people who care about traditional downtowns. The Downtown Specific Plan has been amended to fit the new reality of lessened demand for storefront retail. Vallejo is working its way through its fiscal crisis and on to solid financial footing. On November 8, 2011, Vallejo voters approved Measure B, a one percent sales tax to enhance city services. The City Council set aside a minimum of 30 percent of the Measure B sales tax revenue for Participatory Budgeting. Both capital infrastructure projects and program or service projects are eligible, provided that they meet specific criteria. Civic organizations oversee the process by which community members submit, review, and discuss proposals for spending. "Propel Vallejo," funded by Measure B, is a set of long-range planning initiatives, that includes a general plan update, a zoning code update, a specific plan for a major arterial, and an environmental review.

The public-private partnerships that existed under the aegis of the RDA are continuing with the support of Vallejo's strong tradition of civic group involvement. "The Art and Architecture Walk," funded by Measure B and the Participatory Budgeting project, donations, and volunteer work from local businesses and artists, is an interactive website with videos, background information, and maps accessed via QR codes and RFID chips at locations around the Downtown Vallejo Arts and Entertainment District. "Vallejo Art Windows," puts local artists' installations in vacant storefronts. Downtown property owners, the VCAF, and other community groups bring works of art to empty storefronts with the goal of increasing foot traffic in downtown and encouraging the rental of available commercial spaces. The following images show the sculptor Tebby George's installation, "Circle of Portraits," and an image of the host storefront before her installation.

Was developing Vallejo by means of an RDA with the power to sell bonds based on TIF the right way or the only way to attract investment? California was the first state to use TIF for redevelopment, and the first to give it up. Because cities and counties could pledge not only their own share of the property tax increment from redeveloped areas, but also the share of schools and special districts, the state was forced to back fill the revenue lost to schools. Redevelopment agencies were diverting funds from these other entities to subsidize tax generating commercial properties. The Public Policy Institute of California's 1998 report, "Subsidizing Redevelopment in California," [pdf] concluded thusly: "redevelopment projects do not increase property values by enough to account for the tax increment revenues they receive. Overall, the agencies stimulated enough growth to cover just above half of those tax revenues. The rest resulted from local trends and would have gone to other jurisdictions in the absence of redevelopment." Other researchers contend that cities and counties have unlimited ways to achieve redevelopment objectives if they are willing to spend their own tax revenues. Other options include public -private partnerships, lease revenue bonds, industrial revenue bonds, tax reimbursement contracts, infrastructure financing districts, infrastructure privatization, and parking authority privatization contracts.

Some criticisms of using TIF for redevelopment were motivated by anti-planning sentiment. A post titled, "Urban Renewal Dead in California," on The Antiplanner, writes: "It is conceivable that, somewhere, sometime, a TIF project was truly worthwhile. In general, however, TIF was mainly a way for cities to build empires, elected officials to engage in crony capitalism, and urban planners to practice social engineering. Almost all of those 'transit-oriented developments' that were supposedly stimulated by light rail and streetcars were really simulated by TIF. Nearly all of the cases of cities using eminent domain to take private property and give it to developers involved TIF."

Cities need to access capital markets for construction and infrastructure financing; a viable downtown is important to sustaining civic community. Disinvestment takes an even greater toll on downtowns struggling to find purpose when retail is no longer an option for their small-scale storefronts. Without the ability to attract large-scale redevelopment, Vallejo is preserving its pedestrian friendly downtown of grid pattern streets and small blocks by engaging civic groups and targeting smaller projects, such as facade restoration, with its Measure B funds and its Participatory Budgeting tool. When the good times return, new construction may replace the surface parking lots and the old buildings that lack significance, but the scale and pedestrian orientation will remain. New housing and commercial spaces reinvigorated peninsula downtowns such as Redwood City and Palo Alto for new residents and workers. Vallejo needs to be preserved for a time when technology and ways of working not yet imagined make this small historic city on the bay desirable enough to support big plans.

As Tanvi Misra writes in a CityLab post, "How Hyperconnected Cities Are Taking Over the World, "second-tier cities shouldn't get hollowed out and neglected. They should get more connected to the big cities. They become back offices, back-end, supply-chain providers, lower-cost manufacturing centers—they become part of that urban area." Vallejo is connected economically and culturally to the thriving San Francisco Bay region. Every support for its continued vitality should be provided by the state and region.

[The author wishes to thank Alea Gage, of the Vallejo Economic Development Department, and Annette Taylor, of the Vallejo Planning Department, for their assistance with this article.]

Maui's Vacation Rental Debate Turns Ugly

Verbal attacks, misinformation campaigns and fistfights plague a high-stakes debate to convert thousands of vacation rentals into long-term housing.

Planetizen Federal Action Tracker

A weekly monitor of how Trump’s orders and actions are impacting planners and planning in America.

In Urban Planning, AI Prompting Could be the New Design Thinking

Creativity has long been key to great urban design. What if we see AI as our new creative partner?

San Francisco Mayor Backtracks on Homelessness Goal

Mayor Dan Lurie ran on a promise to build 1,500 additional shelter beds in the city, complete with supportive services. Now, his office says they are “shifting strategy” to focus on prevention and mental health treatment.

How Trump's HUD Budget Proposal Would Harm Homelessness Response

Experts say the change to the HUD budget would make it more difficult to identify people who are homeless and connect them with services, and to prevent homelessness.

The Vast Potential of the Right-of-Way

One writer argues that the space between two building faces is the most important element of the built environment.

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.

Gallatin County Department of Planning & Community Development

Heyer Gruel & Associates PA

JM Goldson LLC

Mpact (founded as Rail~Volution)

City of Camden Redevelopment Agency

City of Astoria

Jefferson Parish Government

Camden Redevelopment Agency

City of Claremont