Neighborhood-scale sustainable development is flourishing, as are tools for assessing and certifying the triple bottom line of projects. Ten neighborhood rating tools are reviewed for their best fit for planners, developers, and communities.

As real estate continues to recover from the recession, large development projects are reappearing in the construction pipeline. And with these new developments comes more interest in assessing their triple bottom lines and effects on neighborhood sustainability. Neighborhood-scale action is now widely recognized as essential to achieving community-wide green goals. This recognition, and an absence of public policy leadership, has prompted a number of interest groups to create voluntary green rating tools aimed specifically at neighborhoods.

The growth of these systems is a global phenomenon. In addition to the United States and Canada, standardized neighborhood assessment tools are available in Europe, Asia, Australia, Latin America, and Africa. A majority are operated by green building or sustainability non-profits that support themselves, in part, on certification fees; while others offer simple, no-cost checklists or web-based rating processes. The more elaborate systems rate a myriad of characteristics and performance metrics, mainly in the built environment, and then award levels of certification based on a scale of points earned by an area’s green features. Examples of rating categories include walkability, energy and water use, materials and waste management, avoidance of sensitive resources, and human health and well-being. Notable neighborhood assessment tools in North America include:

- LEED for Neighborhood Development (ND). A fee-based certification system for new land development operated by the U.S. Green Building Council—approximately 150 projects certified since 2007, but only about a dozen actually constructed. Training and credential are also available. Interestingly, there’s been as much use of ND for local policy-making as for project certification, and USGBC is considering a service that will evaluate subarea plans for local governments.

- SITES (Sustainable Sites Initiative). A fee-based certification system for sustainable land design and development of new or renovated sites up to the neighborhood level—operated by the Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center at the University of Texas at Austin, the U.S. Botanic Garden, and the American Society of Landscape Architects. There are approximately 30 pilot projects certified under the 2009 tool, which is being updated and released as SITES v2 in 2014 and credentialing is also being considered. This is the go-to system for sustainable landscape design and stewardship.

- Living Community Challenge (LCC). An innovative fee-based certification system with the most ambitious standards for new land development of all such tools. Launched in May 2014 by the International Living Future Institute, the system has several notable features: any type of project is eligible, from a single street up to a master planned neighborhood; projects are categorized on a New Urbanist transect; every standard is mandatory; all new buildings must certify under the companion Living Building Challenge system; equity issues get more attention than in any of the other tools; and certification is based on actual performance.

- Green Land Development. A fee-based certification system for new residential land development—operated by Home Innovation Research Labs, an arm of the National Association of Home Builders. Approximately 22 projects have been certified. The tool relies on community plans for vetting project location and is notable for its third-party onsite verification.

- Envision.Two assessment tools are available from the Institute for Sustainable Infrastructure:a no-cost checklist and a fee-based certification system. Several projects have been certified since 2010, and a credential is available. The tool is notable for its triple-bottom-line perspective of neighborhood- and community-scale utility and transportation systems.

- EcoDistricts. A no-cost "how to" framework of process and performance areas for new and, notably, existing neighborhoods. EcoDistricts isn't a top-down rating system, but rather, stakeholders create a bottom-up assessment of each district, in effect defining their own rating. Since 2009, several dozen communities have received technical assistance after applying the framework. The tool is distinguished by its emphasis on community-based organizing and management of neighborhood activities, and it's being updated in 2014 to become a Global Protocol.

- Walk Score. This is the most prominent of an emerging class of online, no-cost, single-topic rating tools designed for the general public as well as practitioners. Walk Score is a harbinger of easier, faster rating tools, like the Center for Neighborhood Technology's Housing + Transportation Affordability Index, U.S. EPA’s Smart Location Database, and AARP’s upcoming Livability Index.

- Green Neighborhoods. A fee-based certification system for existing neighborhoods operated by Audubon International. Several neighborhoods have been awarded levels of achievement over the past ten years. In addition to assessing neighborhoods with sustainability indicators, the system is notable for its low cost, an ongoing membership business model, and a requirement that participating neighborhoods complete at least one green implementation project annually for at least three years.

- Enterprise Green Communities. A no-cost, online certification system operated by the Enterprise Community Partners non-profit for projects with new affordable housing. Over 37,000 units of green affordable housing have participated in the program over the past ten years. The current system is a good example of an online procedure that minimizes time and expense for users. It’s also notable for onsite verification and post-construction reporting.

- 2030 Districts. This is the real deal. In effect, neighborhoods rate their own resource consumption on an ongoing basis. 2030 Districts has a unique focus on existing neighborhoods and uses a bottom-up process of building owners voluntarily sharing energy, water, and vehicle emissions data and committing to common reduction goals from theArchitecture 2030Challenge. Initially limited to large buildings in the central business districts of Seattle, Cleveland, Pittsburgh, Los Angeles, and Denver, the program is expanding to other cities and small building owners. It’s a stand-out approach that really walks the talk and could be a model for broader systems outside of central business districts.

Notable neighborhood systems outside North America include: BREEAM Communities in the United Kingdom, CASBEE for Urban Development in Japan, DGNB for Urban Districts in Germany, Green Star Communities in Australia and South Africa, Green Mark for Districts in Singapore, and Pearl Community-Estidama in Abu Dhabi.

All of the above are just the standardized tools designed for widespread application. Beyond these tools are numerous one-off neighborhood rating or indicator tools created by local groups, including San Antonio, Seattle, Baltimore, and Madison. The National Neighborhood Indicators Partnership provides valuable resources on local assessment systems, and two other community-scale rating tools with implications for neighborhoods are STAR Communities and the American Planning Association’s new Comprehensive Plan Standards for Sustaining Places.

Because of their relative newness (except for Enterprise, none of the standardized systems existed ten years ago), there’s been little academic investigation of neighborhood tools. But that’s likely to change as such systems start to produce cohorts with measurable outcomes and lessons learned. The field is ripe for comparative analysis; in a test, my firm is applying multiple tools to a single project to see how it scores under a range of tools. The University of Westminster in the United Kingdom has begun to track eco-city schemes globally, including many at the neighborhood level. Their latest survey found 43 frameworks, which suggests there could really be in excess of 100 tools worldwide, and a good share of those are likely scaled to the neighborhood or district level. Searching the Community Indicators Consortium database with the keyword "neighborhood" returns a mostly U.S. inventory of two-dozen one-off local systems.

All this activity has caught the eye of the International Organization for Standardization (ISO), whose Technical Committee 268 on Sustainable Development in Communities was created in 2012 to formulate global standards for sustainability assessment principles, vocabulary, and indicators. Through voluntary adoption of international standards, ISO hopes to foster better info-sharing and comparison of tool performance. A global survey of smart infrastructure indicators has been produced, and draft standards are in the works.

At the same time, funders in the United States have taken note of neighborhood tools by conditioning financial assistance on consistency with rating criteria. Nationally, the Department of Housing and Urban Development references LEED-ND alignment in its General Section grant guidelines and in its Choice Neighborhood and HOPE program criteria. At the state level, New York’s Energy Research and Development Authority recommends use of LEED-ND by its Cleaner, Greener Communities grantees. And at the local level, the Funders Network for Smart Growth and Livable Communities, in cooperation with the Urban Sustainability Directors Network, recently finished a survey of district-scale sustainability schemes to, in part, inform grant-making by member foundations like Summit, Surdna, and Kresge.

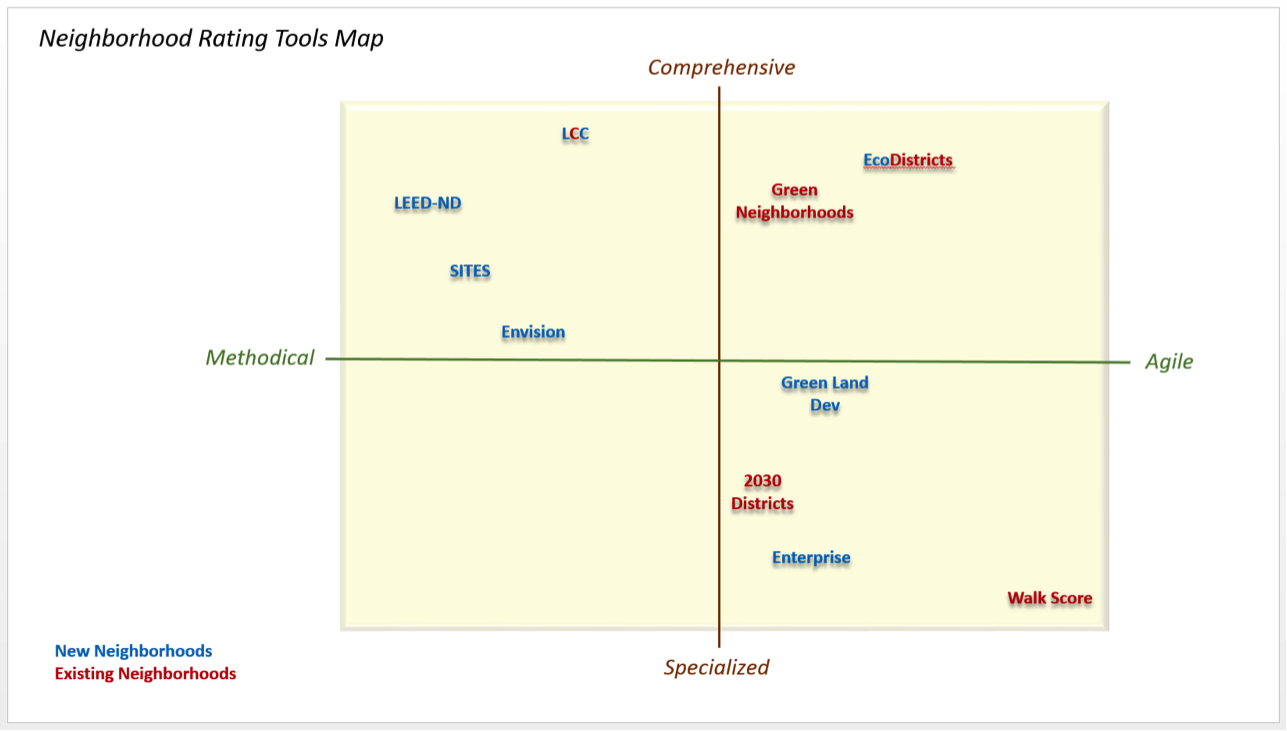

So, where do all of these options leave communities, developers, and designers who are interested in using neighborhood tools? There are big differences between each of the tools, and several criteria should be considered when making a selection, beginning with an alignment with user values. The systems outlined above provide valuable structures for communicating among stakeholders about neighborhood qualities and goals. But are they rating the right considerations? How triple is their bottom line? Who are the beneficiaries of a tool's particular rating? Most systems have a strong environmental bias, with token nods toward social equity and economic prosperity, but Enterprise is the exception, with its focus on housing and quality neighborhoods for low-income households.

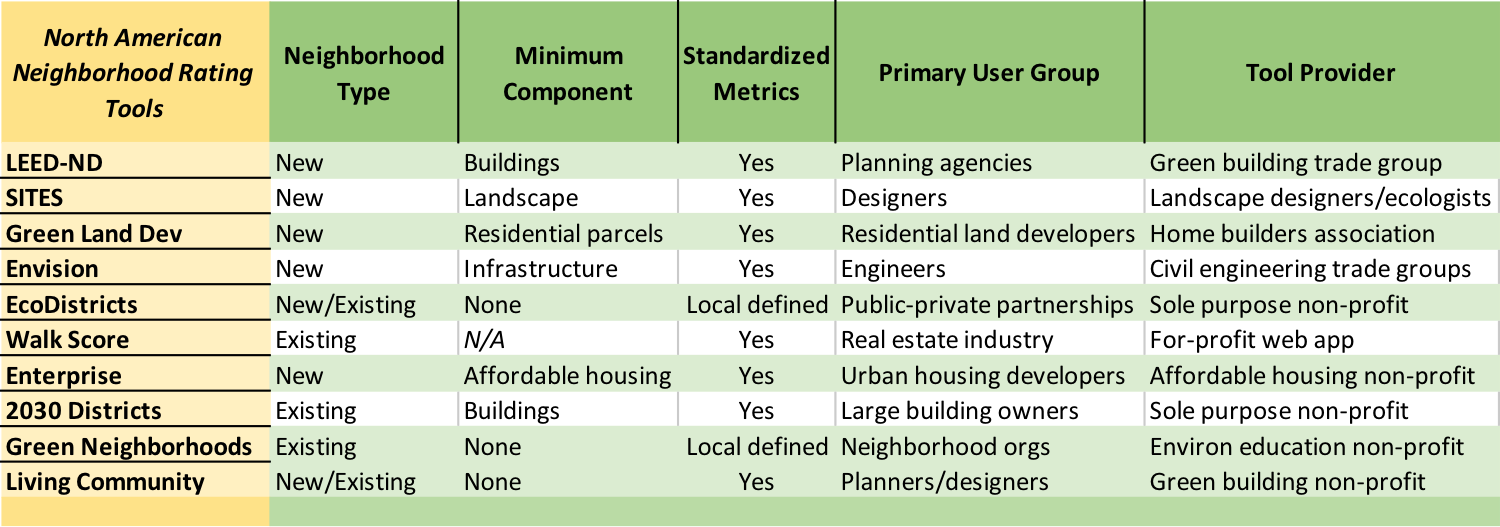

The rating tools are also differentiated by type of eligible project. Only EcoDistricts, Green Neighborhoods, Walk Score, LCC, and 2030 Districts assess existing neighborhoods, while others focus on new construction (and equivalent major renovation). Except for EcoDistricts, LCC, and Green Neighborhoods, all have a minimum component requirement, such as residential parcels for Green Land Development, affordable housing for Enterprise, or infrastructure for Envision.

If a tool’s scope is appropriate, the next question is how participatory or inclusive it is. How locally adaptable is it? Is it a proprietary system applied by practitioners in relatively closed technical processes, or does it rely on open source, bottom-up engagement of residents? 2030 Districts excels in the latter respect, directly engaging neighbors to share data and take collective action toward common goals. Also, EcoDistricts freely distributes its framework, relying on grass-roots stakeholder engagement to assess conditions, tailor goals, and prioritize implementation projects.

What about verification? Do projects actually deliver on the environmental and social benefits they claim? Disappointingly, a minority of tools include onsite verification of green measures, and even fewer have ongoing reporting requirements to monitor progress toward commitments. In contrast, 2030 Districts is an exemplar, with its rating built on solid empirical results, gathered over time. Living Communities Challenge and Green Neighborhoods also monitor performance over time and fold that feedback into project operations.

How affordable and time-consuming are these tools? Some are free and require only minutes or hours to use, while others require tens of thousands of dollars and months to navigate an elaborate certification processes. Costs and time to use the tools are driven by the business models of each system and a wide range of complexity in the tools, from LEED-ND’s intricacy to the relative simplicity of Green Land Development.

Do we need so many standardized systems for rating neighborhood sustainability? Probably not. Some consolidation could make sense to break down silos and share overhead. Why have separate rating systems for buildings, landscape, and infrastructure, especially if integrative design is a goal of all three? On the other hand, there’s legitimate need for specialized tools, like EcoDistrict’s focus on process and ongoing management.

So far, the market response to most of the systems has been pretty timid, but in fairness, some of the slow rate of adoption can be partially explained by the recession. As the economy rebounds, the question will be which tools deliver enough value to get market traction and, ultimately, produce real impacts on the ground. Walk Score and its brethren are sure to prosper at the convenient, no-cost, Big Data end of the continuum, while at the other end, hand-crafted systems like EcoDistricts, 2030 Districts, and Green Neighborhoods should find grassroots support for producing bankable results, neighborhood-by-neighborhood.

Regardless of position on the continuum, impact and endurance are more likely to go to those systems that conform to emerging international standards, are affordable, and can verify and articulate tangible, equitable benefits. Or maybe local one-off tools will prove to be as good or better than standardized systems in making meaningful value propositions. Either way, the explosive growth in neighborhood rating tools over the past ten years has likely reached a plateau, and now it’s time to determine which ones are really adding value, and for whom.

Eliot Allen LEED AP-ND, is a Principal at Criterion Planners of Portland Oregon, and a specialist in using sustainability indicators to help designers and citizens fashion places that are measurably more livable and environmentally responsible. He has supervised over 200 LEED-ND neighborhood certification reviews for the U.S. Green Building Council and Green Building Certification Institute; is a member of the SITES rating system technical core committee; and faculty, facilitator, and global protocol advisor for EcoDistricts. Eliot is a co-recipient of EPA’s Climate Protection Award for the Chula Vista California Climate Action Plan; the Congress for the New Urbanism’s Charter Award for the SmartCode; and the APA Sustainable Communities Division Plan Award for the Imagine Austin Comprehensive Plan. He is a former chair of Portland’s Energy Commission and currently serves on the Urban Planning Task Group of the American Society for Testing & Materials.

Eliot Allen LEED AP-ND, is a Principal at Criterion Planners of Portland Oregon, and a specialist in using sustainability indicators to help designers and citizens fashion places that are measurably more livable and environmentally responsible. He has supervised over 200 LEED-ND neighborhood certification reviews for the U.S. Green Building Council and Green Building Certification Institute; is a member of the SITES rating system technical core committee; and faculty, facilitator, and global protocol advisor for EcoDistricts. Eliot is a co-recipient of EPA’s Climate Protection Award for the Chula Vista California Climate Action Plan; the Congress for the New Urbanism’s Charter Award for the SmartCode; and the APA Sustainable Communities Division Plan Award for the Imagine Austin Comprehensive Plan. He is a former chair of Portland’s Energy Commission and currently serves on the Urban Planning Task Group of the American Society for Testing & Materials.

Planetizen Federal Action Tracker

A weekly monitor of how Trump’s orders and actions are impacting planners and planning in America.

San Francisco's School District Spent $105M To Build Affordable Housing for Teachers — And That's Just the Beginning

SFUSD joins a growing list of school districts using their land holdings to address housing affordability challenges faced by their own employees.

Can We Please Give Communities the Design They Deserve?

Often an afterthought, graphic design impacts everything from how we navigate a city to how we feel about it. One designer argues: the people deserve better.

Engineers Gave America's Roads an Almost Failing Grade — Why Aren't We Fixing Them?

With over a trillion dollars spent on roads that are still falling apart, advocates propose a new “fix it first” framework.

The European Cities That Love E-Scooters — And Those That Don’t

Where they're working, where they're banned, and where they're just as annoying the tourists that use them.

Map: Where Senate Republicans Want to Sell Your Public Lands

For public land advocates, the Senate Republicans’ proposal to sell millions of acres of public land in the West is “the biggest fight of their careers.”

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.

Borough of Carlisle

Smith Gee Studio

City of Camden Redevelopment Agency

City of Astoria

Transportation Research & Education Center (TREC) at Portland State University

City of Camden Redevelopment Agency

Municipality of Princeton (NJ)