October 8, 2024, marks the centennial of the publication of what would soon become the Los Angeles Traffic Ordinance — a landmark on the road toward our car-dominated status quo.

Americans drive much more than the people of any other country – and it’s not by preference. We’re dependent on driving, not in love with it. The consequences are expensive, unsustainable and lethal. In 2022, 42,514 people died in traffic violence on America’s road and streets.

How did we get here? Americans did not choose car dependency. We didn’t vote for it, and it was not the winner in a free market competition. The real answer is complex, but a single turning point reveals an essential part of the story.

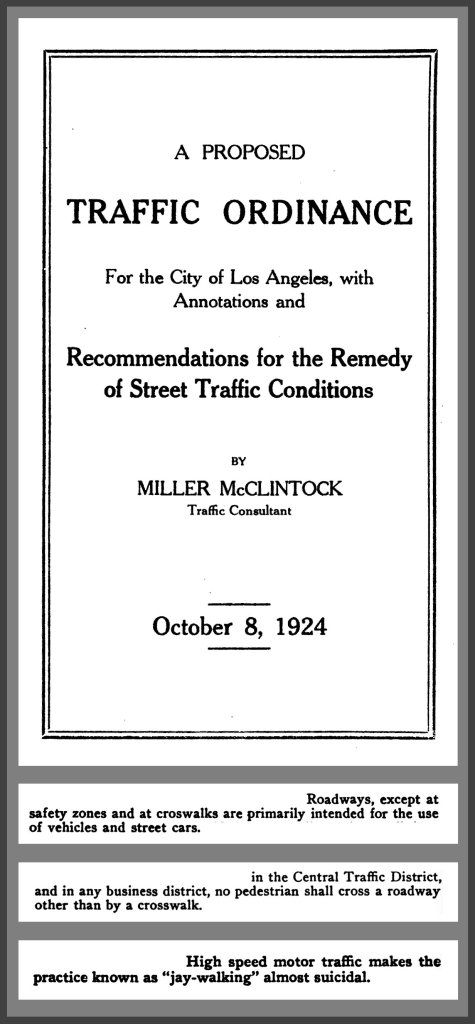

That turning point was 100 years ago today. In Los Angeles, on Wednesday, October 8, 1924, a 30-year-old English teacher named Miller McClintock submitted his proposal for a new city traffic ordinance to the City of Los Angeles. McClintock wrote it at the request of America’s most successful Studebaker dealer: Paul Hoffman, just 33. Hoffman had used his business prowess not just to sell Studebakers, but also to win the chairmanship of the Los Angeles Traffic Commission, a group of businessmen who had cultivated close relationships with key members of the Los Angeles City Council.

Hoffman wanted a new traffic ordinance for Los Angeles that would favor his customers. He aspired to a city in which drivers had priority over pedestrians. Three decades later, he explained his motives plainly: “I claim no altruism whatsoever for that early interest,” he told an audience of young traffic professionals in 1956. “I was in the automobile business in Los Angeles.”

As a car dealer, Hoffman could not write a traffic ordinance himself. “Studebaker Salesman Proposes New Traffic Ordinance” was not a winning headline. So instead, in July 1924 Hoffman commissioned Miller McClintock to write it. The traffic commission put McClintock on retainer as its “traffic consultant,” a title that was not an obvious fit for an English teacher. But McClintock was also working on a PhD in municipal government at Harvard University, and the subject of his thesis was city traffic. That was sufficient, Hoffman calculated, to give McClintock the credibility he needed.

When ‘safe streets for all’ was the goal

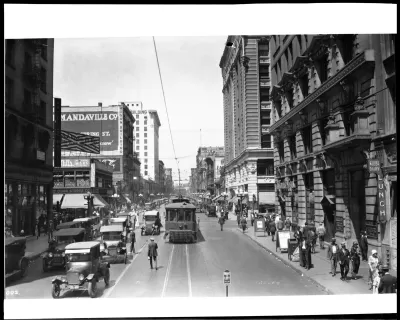

In 1924 there were already 16 million cars on American roads and streets, but the smart bet then was that driving your own car would never be the main way to get around a city. People walked. City sidewalks were often crowded with pedestrians. Street railways made walking practical. Streetcar lines reached into the suburbs and the networks were usually so extensive that people could get almost anywhere without a car. Those who tried to drive found the going slow. Pedestrians were everywhere, and a driver stuck behind a streetcar often couldn’t pass it. And if you injured or killed a pedestrian — anywhere in the street — the driver was likely to be found liable. After all, streets were for everyone, and a person who chose to operate a dangerous machine was responsible for the consequences.

Automobiles and pedestrians were a deadly mix. Traffic deaths in cities were high and rising steeply, and most of those killed were pedestrians, often children. People did not think about safety like we usually do today. They did not ask, “How can we make driving safer for people in cars?” That’s because streets were not primarily for drivers. They were for everyone. So instead, people asked, “How do we keep streets safe for all?” And since drivers were a small minority operating dangerous machines, the usual answer was to restrict driving.

Insiders in automobile businesses had no confidence that driving would ever become the usual way to get around a city for most people. In cities, most people who could afford a car weren’t buying one. They had good alternatives, the rules prevented fast driving, and anyone who tried driving fast anyway had to share streets with pedestrians and their streetcars. And as death tolls rose, the proposals to restrict driving grew more vocal. Pedestrians far outnumbered drivers, so motordom could not turn to democratic processes for relief.

Motordom and the end of the pedestrian-first era

At that time, enterprises with a business interest in automobiles called themselves “motordom.” Motordom recognized that its greatest obstacle to future of ubiquitous driving in cities was the way most people looked at the problem. As long as the usual question was “How do we keep streets safe for all?” motordom could not win. Motordom organized to change this.

In 1922 an insider in motordom, Edward Mehren, concluded: “The obvious solution … lies only in a radical revision of our conception of what a city street is for.” If streets were for automobiles, drivers would have priority over pedestrians. Then pedestrians — not drivers — would be restricted, and pedestrians would be responsible for their own deaths. McClintock’s traffic ordinance was a critical step in the “radical revision.”

On behalf of the Los Angeles Traffic Commission, McClintock submitted his traffic ordinance to city council on October 8, 1924. It was far from the first ordinance to provide for the regulation of pedestrians, but it was by far the most influential.

“High speed motor traffic makes the practice known as ‘jay-walking’ almost suicidal,” McClintock explained, reversing the then-prevalent perception that high-speed motor traffic should be slowed down wherever people walk.

The proposed ordinance specified that “roadways, except at safety zones and at crosswalks are primarily intended for the use of vehicles and street cars.” In business districts, McClintock’s ordinance confined pedestrians: “no pedestrian shall cross a roadway other than by a crosswalk.”

This rule is unsurprising today only because we have all grown up with the legacy of this influential ordinance. In fact, judges had ruled consistently that streets were as much for pedestrians as for anyone else, and that motorists’ duty of care was far greater. McClintock’s ordinance was the greatest single factor in overturning this legal standard — and not just in Los Angeles.

Giving drivers precedence

With some revisions, the city council adopted McClintock’s ordinance. It became effective on Saturday, January 24, 1925. Though implementation was far from incident-free, it won the admiration of motordom coast to coast. Meanwhile Studebaker awarded Hoffman by making him a corporate vice president. For McClintock, the company endowed the first national institute of traffic engineering and made the author of the Los Angeles Traffic Ordinance its first director.

In California, motordom promoted the LA ordinance throughout the state. McClintock, the Automobile Club of Southern California, and the California State Automobile Association developed it into a Uniform Traffic Ordinance for California cities.

Thereafter the ordinance became the model for cities throughout the United States. In 1927 and 1928 insiders in motordom drafted a Model Municipal Traffic Ordinance, adapting it from the Los Angeles traffic ordinance. Just as Hoffman had needed McClintock to give the L.A. ordinance credibility as the work of an impartial expert, national motordom used the U.S. Department of Commerce as an intermediary in the model ordinance. It was issued by the Commerce Department, though it was written by a committee chaired by a Cadillac salesman. By late 1930, 23 cities beyond California had adopted the model ordinance, in whole or in part. New Jersey, New York, and Wisconsin adopted versions of it as state law.

It is the ancestor of the typical traffic ordinances in state codes and municipal ordinances today. It superseded common law principles by which pedestrians had rights at least equal to those of other street users.

Once implemented, these ordinances became grounds for raising speed limits, deterring walking as a cause of “delay” (to motorists), and eventually even removing many marked crosswalks because of their supposed tendency to give pedestrians “a false sense of security.” Meanwhile the street railways, in part because of interference from growing motor traffic, went bankrupt and were scrapped. Eventually even people who could not afford a car were often compelled to buy one. Walking in America did not just decline; it was deterred.

One hundred years later

The origins of car dependency in the United States are mostly forgotten today. We fill this vacuum of memory with various notions, above all that we Americans just prefer to drive and chose car dependency for ourselves. Such ideas are ahistorical and serve to excuse and perpetuate an expensive, unsustainable and deadly status quo. On the centennial of the Los Angeles Traffic Ordinance, it’s worth remembering that many of our forebearers who chose cars did so only as a last resort. We never chose car dependency.

Peter Norton is associate professor of history in the Department of Engineering and Society at the University of Virginia. He is the author of Fighting Traffic: The Dawn of the Motor Age in the American City (MIT Press) and of Autonorama: The Illusory Promise of High-Tech Driving (Island Press, use code PLANETIZEN for a discount).

The Pedestrian Safety Crisis in the U.S.

Maui's Vacation Rental Debate Turns Ugly

Verbal attacks, misinformation campaigns and fistfights plague a high-stakes debate to convert thousands of vacation rentals into long-term housing.

Planetizen Federal Action Tracker

A weekly monitor of how Trump’s orders and actions are impacting planners and planning in America.

San Francisco Suspends Traffic Calming Amidst Record Deaths

Citing “a challenging fiscal landscape,” the city will cease the program on the heels of 42 traffic deaths, including 24 pedestrians.

Defunct Pittsburgh Power Plant to Become Residential Tower

A decommissioned steam heat plant will be redeveloped into almost 100 affordable housing units.

Trump Prompts Restructuring of Transportation Research Board in “Unprecedented Overreach”

The TRB has eliminated more than half of its committees including those focused on climate, equity, and cities.

Amtrak Rolls Out New Orleans to Alabama “Mardi Gras” Train

The new service will operate morning and evening departures between Mobile and New Orleans.

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.

Heyer Gruel & Associates PA

JM Goldson LLC

Custer County Colorado

City of Camden Redevelopment Agency

City of Astoria

Transportation Research & Education Center (TREC) at Portland State University

Jefferson Parish Government

Camden Redevelopment Agency

City of Claremont