The role of rivers in urban areas shifted in recent years from production to consumption. Now, access to a river's waterfront has become a highly valued amenity within cities.

The role of rivers in cities has radically evolved over the last century. Originally understood as purely utilitarian infrastructure, rivers are now appreciated as a catalyst and focus for a wide range of urban amenities. Another, more economics-oriented way to phrase the new role of rivers is that their function has moved beyond production to include consumption.

While rivers were being supplanted by trains, trucks, freeways, telephones, airports, and then internet communications, their roles in expanding consumption have been aided by a wide variety of strategies with a consistent underlying principle: access to a waterfront, and active use of it, have become highly valued amenities within cities. There is now a global effort to introduce more leisure-time activities on riversides, even in those cities which have previously lacked them.

“Amenities” have been defined broadly as “non-market transactions.” The economists Glaeser, Kolko, and Saiz (2004) have built many models of consumption and lifestyle, but they largely assume that individuals act in isolation and that each amenity (e.g., restaurant or museum) can similarly be analyzed atomistically. In contrast, our research seeks to join the amenities and consumption work from economics and cultural geography with core social and cultural processes.

This article looks at a variety of river-oriented developments in cities across the world. It is not intended to be a comprehensive list of all such efforts, but a demonstration of the methods of scenes analysis used for considering these ideas. One major lesson from our work is not to focus on a single amenity, like a beach, but to consider how hundreds of amenities combine to create an integrated whole, with deep meaning, with nature, with people. We call these scenes.

Our 15 scenes dimensions are distilled from the work of philosophers, novelists, social theorists, and technical experts in many subfields over hundreds of years. We work with collaborators in France, Spain, Italy, Poland, Canada, Japan, and South Korea, who help identify critical elements and distinct combinations of these dimensions of scenes in ways that enhance our understanding of new scenes in these, and other, places. We have actively consulted with such cities as Paris, Seoul, and Chicago, connecting scenes with policy issues and completing books and many papers on each.

These dimensions incorporate measures of hundreds of individual variables such as education, occupation and tastes of individual people. We combine them with ecological level system variables such as climate and density of construction and traffic flows.

Our scenes approach sharpens consumption specifics beyond random noise. These ideas have been codified in our books, of which Scenescapes and The City as an Entertainment Machine are two. We have developed ways of doing comparative national and international quantitative analyses of scenes dynamics, and rich case studies of one city's or one neighborhood’s specific scenes dynamics.

The term scene has a self-conscious theatricality while building on publicly accessible street amenities like open food markets, which citizens freely enter and leave. These ideas extend the German tradition of consumption from Wagner and Walter Benjamin, plus anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss’ approach to studying hundreds of myths.

The scenes concept does not replace existing approaches like historic preservation or modernism or healthy exercise via swimming. The scene stresses how smaller parts combine synergistically; the whole becomes more than its parts, if we look and act holistically. Our 15 key dimensions of scenes are measured with millions of data bits across countries from China to the United States.

Empirical issues are complicated not only by these issues of “high” and “low,” but also by the fact that cultural activity involves more than the arts. Cultural meanings and codes are expressed in, and define, different styles of life and situations, shaping what it means to frequent restaurants, cafes, sporting events, parks and more. And culture is more than the “cultural industry” or “cultural districts” (Alexander 2003), because cultural amenities are not only, or even mainly, sites of economic activity, and their attraction is not reducible to economic factors; cultural amenities may well generate jobs and economic development, but they do so (at least in part) because they provide places where people can express their lifestyles, generating independent value (Currid 2007).

The role of government is one visible difference in culture. Governments with a more socialist or urban planning orientation have been more visibly active in beautifying individual cities, resulting in enhanced settings for such activities as the Olympics. Similarly, a few mayors in cities like Chicago, Paris, and Berlin have explicitly used generous government funding to promote riverside transformation in ways that citizens in others, like Toronto and Seoul, have voted down. Some of the most dramatic Western projects have been funded not only locally, but directly by the national government, such as in Washington, D.C., Paris, and London, all of which feature rivers in their tourism repertoire.

In another example, bus systems in most cities focus on work trips. Instead, Paris and the Chinese city of Chengdu have changed bus routes to add stops facilitating river swimming, illustrating how simply thinking more about scenes and consumption can transform river culture and specific policies today.

We can talk about river scenes with many historical examples, but the scenes analysis provides a mechanism, a sort of chemical table of elements, for capturing some of the key elements that can be combined to connect to the river and to the visitors brought by water, such as restaurants or jazz clubs. But amenities act jointly with human capital. Why? They are the cheese, or correction, the three star meal, attracting talent. They transform a location into a scene. Human capital theory is thus not incorrect, but contextually incomplete, underspecified, in that it does not explain where and why human capital locates. Since talent is in fact highly mobile, our amenities theory enters critically to close the causal loop, joining jobs with human capital.

Efforts to improve the “quality of life,” via festivals, bicycle paths, or culture are recognized as central not just for consumption but for economic development, which is increasingly driven by consumption concerns. Amenities benefit all firms as well as citizens in the area. They often enhance the local distinctiveness (of architecture or a waterfront) by improving the locality, rather than just making it cheaper for one business. Human capital development of the local workforce, like amenities, is a public good for the location.[1]

The 15 scenes dimensions are illustrated below.

| Table 1: Analytical Components of Scenes I: Theatricality, Authenticity, Legitimacy | ||

| Theatricality | Legitimacy | Authenticity |

| Mutual self-display | Discovering the real thing | Acting on moral bases |

| Seeing and being seen | Touching ground | Listening to duty |

| Appropriate vs. Inappropriate | Genuine vs. Phony | Right vs. Wrong |

| Appearance | Identity | Intentions to act |

| Performing | Rooting | Evaluating |

| Table 2: Analytical Dimensions of Scenes: dimensions of theatricality, authenticity, and legitimacy | |

| Theatricality | |

| Exhibitionistic | Reserved |

|

Glamorous |

Ordinary |

| Neighborly | Distant |

| Transgressive | Conformist |

| Formal | Informal |

| Authenticity | |

| Local | Global |

| State | Anti-State |

| Ethnic | Non-Ethnic |

| Corporate | Independent |

| Natural | Artificial |

| Rational | Irrational |

| Legitimacy | |

| Traditional | Novel |

| Charismatic | Routine |

| Utilitarian | Unproductive |

| Egalitarian | Particularist |

| Self-Expressive | Scripted |

We join these attributes with specific propositions about which amenities can create synergy and a higher return on investment, what the economics term “multiplier” affects. Additionally, we consider the economic stress on individual components, such as museums. Finally, we combine hundreds of amenities to capture the more subtle components of scenes in ways that can be built up from past components. In this way, traditional cultural elements like panda bears and spicy food can join the bright river lights in a more powerful riverfront culture.

An abbreviated list of cities considered in this manner includes:

- Paris

- New York

- Chicago

- Milwaukee

- Vancouver

- Seoul

Social Context

A number of Impressionist paintings presage rivers’ evolution from production to consumption. Perhaps the most famous of these paintings are Georges Seurat’s A Sunday on La Grande Jatte (1884-1886) and Pierre-Auguste Renoir’s Luncheon of the Boating Party (1882). Both paintings highlight groups of people drawn to the waterfront for social or athletic activities, pursuits that have broadened enormously from those of the late 19th century.

Paris

Haussmann’s 19th century reconfiguration of the streets of Paris was revolutionary. In the 21st century, the city experienced a similarly revolutionary effort to encourage more leisure-time activities on the waterfront. During the summer of 2002, Mayor Bertrand Delanoë initiated an effort to close motorized traffic on both banks of the Seine. These policies have been continued and amplified by Delanoe’s successor, Anne Hidalgo.

Gradually, les Paris Plages has been instituted on both the Right and Left Banks, spanning a two-month period from early July to late August. In the early years, thousands of tons of sand were trucked in along the riverfront each year, and removed at the end of the summer when the areas reverted back to highway use. Now, grass and trees have replaced the road surface on the Right Bank, accompanied by potted palms, chairs, recliners, and pop-up cafes.

The Left Bank hosts games, activities, art displays, restaurants, dancing, and children's activities as well as sitting areas. In the19th arrondissement, the northeast part of the city, the Bassin de la Villette offers three large swimming pools floating within the Canal Saint-Martin. The Bassin also offers other waterfront activities, including pedal boats, paddle boats, kayaks, and canoes. Elsewhere in Paris, outdoor sports activities are encouraged at the Trocadero fountains and have been offered in front of the Hotel de Ville.

… the plage creates a sense of urban community. Entrance is free, and most of its amenities—the fleet of well-maintained loaner bikes, and even the board games—are either low-cost or free, too. People from every neighborhood and social background can be found here. Easy to reach on public transport, even from the banlieues, the plage vigorously counteracts ethnic and class ghettoization… the plage has proved itself not only commercially viable but a huge moneymaker for the city. It pays for itself many times over.

New York

Consistent with its expanding efforts over the last 40 years—which include Battery Park City and Governors Island—New York City opened the 2.4- acre Little Island park and live performance space in Spring 2021. The park was designed by Thomas Heatherwick and was largely privately funded by The Diller–von Furstenberg Family Foundation.

The foundation gave $260 million to build Little Island and has committed another $120 million over the next ten years for maintenance and theatrical productions, while New York City contributed an additional $17 million for the esplanade. The state also contributed $4 million. The project was initially conceived by Barry Diller in 2012, and required almost ten years to come to fruition.

Now bourgeois central, the West Side used to be the busiest port in the Americas, a clangorous maelstrom of swinging cables and breaking booms, bulging warehouses and stevedores’ bars.

One of the most controversial aspects of Little Island is the fact that it was so heavily privately funded—there were no advisory groups or board of directors, just influential friends of The Diller–von Furstenberg Family Foundation advising on the desirability of various amenities. Four artists are serving as curators for individual aspects of the programming. They include the dancer and choreographer Ayodele Casel, the playwright/director Tina Landau, the actor Michael McElroy, and the actors, musicians, and storytellers of the PigPen Theater Co.

Chicago

Chicago traditionally used its rivers for production, and the riverfronts became extensive and ugly port areas. During much of the 20th century, the city had a strong focus on the ethnicity of its citizens, including the striking example of the use of green dye in the river on St. Patrick’s Day by Irish political leaders, in conjunction with the day’s parade. Similarly, Chinatown residents enjoyed classic Chinese boat racing, sword display, and family meals in local restaurants.

In the 21st century, the downtown riverfront has been supplemented by major cultural amenities: music, theaters, restaurants, cafés, and other activities, often highlighting the industrial past. Older buildings have been renovated to accommodate these new activities.

Milwaukee

In 1999, the state of Wisconsin, the county of Milwaukee, and the city of Milwaukee collectively approved the removal of the Park East Freeway, a mile-long spur that was built as part of a larger plan to encircle the Downtown business district with expressways.

Using funding from the Intermodal Surface Transportation Efficiency Act of 1991 (ISTEA) and local Tax Incremental Financing, former Mayor John Norquist, a fiscally conservative socialist, began the process of demolishing the freeway, replacing it with an at-grade, six-lane boulevard that is fully connected to the existing and newly re-created street grid. Milwaukee is one of the largest U.S. cities to adopt such a policy.

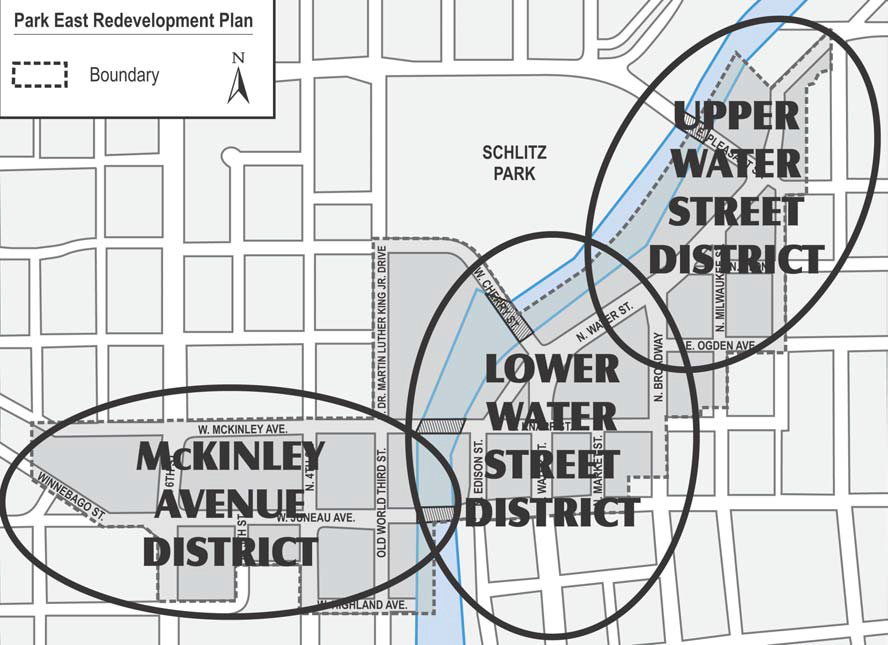

As a result of the freeway’s removal, the city has seen the emergence of three distinct districts in Milwaukee’s downtown: McKinley Avenue, Lower Water Street, and Upper Water Street. The site plan below illustrates these.

Vancouver

In the 1960s, Vancouver’s historic downtown was at risk of being demolished for modern vehicular projects—but an exceptional local protest movement helped transform it into one of North America’s most ‘liveable’ cities.

Today, Vancouver is the only major North American urban center without an inner-city freeway, and the city has the most buoyant real estate market in Canada.

Seoul

At the start of the 21st century, downtown Seoul had freeways with 150,000 cars a day running through. In 2001, Mayor Lee Myung-bak proposed removal of the freeways, to be replaced by two moving lanes of traffic in each direction.

By 2003, the project was completed, and the new riverscape helped elect Lee Myung-bak as president of South Korea in 2008.

Conclusions

The major lesson of scenes work is not to focus on single activities, but to combine analysis of amenities to create an integrated whole with deeper meaning. The scenes concept does not replace past concepts like historic preservation or modernism or healthy exercise via swimming. The scene stresses how smaller parts combine synergistically; the whole becomes more than its parts, if we look and act holistically.

Environmental improvement as a policy arena combines biological and human concerns. Environmental activism, however, is complicated by substantial variations in political leadership, national culture, education of citizens and time.

Western environmental studies long used capitalism and business leadership to explain why environmental controls were not successfully implemented, but closer studies of local decision-making show that business can be strong advocates in some areas but weak in others. By definition, economics and cultural geography don’t consider all possible contexts.

In sum, our Scenes work links the amenities and consumption analyses from the fields of economics and cultural geography with deeper understandings of cultural amenities. Big data about local specifics helps produce improved, more comprehensive theorizing and policy, but just as cultural activity involves more than the arts, big data alone can’t fully illustrate the variety of scenes.

Cultural meanings and codes are articulated in different styles of life and situations, shaping what it means to frequent restaurants, cafes, sporting events, parks and more. And culture is not just the “cultural industry” or “cultural districts”: these may well generate jobs and economic development, but they do so (at least in part) because they provide places where people can express their lifestyles, generating emotional, psychological, and social value. The examples of Paris and Chengdu changing their bus routes to add stops like river swimming encapsulates how simply thinking more about scenes and consumption can transform river culture and specific policies today.

Maui's Vacation Rental Debate Turns Ugly

Verbal attacks, misinformation campaigns and fistfights plague a high-stakes debate to convert thousands of vacation rentals into long-term housing.

Planetizen Federal Action Tracker

A weekly monitor of how Trump’s orders and actions are impacting planners and planning in America.

In Urban Planning, AI Prompting Could be the New Design Thinking

Creativity has long been key to great urban design. What if we see AI as our new creative partner?

Chicago’s Ghost Rails

Just beneath the surface of the modern city lie the remnants of its expansive early 20th-century streetcar system.

Baker Creek Pavilion: Blending Nature and Architecture in Knoxville

Knoxville’s urban wilderness planning initiative unveils the "Baker Creek Pavilion" to increase the city's access to green spaces.

Pedestrian Deaths Drop, Remain Twice as High as in 2009

Fatalities declined by 4 percent in 2024, but the U.S. is still nowhere close to ‘Vision Zero.’

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.

planning NEXT

Appalachian Highlands Housing Partners

Mpact (founded as Rail~Volution)

City of Camden Redevelopment Agency

City of Astoria

City of Portland

City of Laramie