Regulating alcohol in the public realm.

Picture public drinking in the United States and chances are you imagine revelers at Mardi Gras or a down-and-out worker clutching a brown bag on their lunch break. Yet the early American colonists drank daily, and on the journey from England to Massachusetts Bay, ships carried more beer than water. The log book of the Mayflower records "our victuals being much spent, especially our beere," the ship had to make an early stop at Plymouth. While drunkenness was seen as a vice, drinking itself was commonplace for men, women, and even children. "Since the beginning," writes Susan Cheever in Drinking in America: Our Secret History, "drinking and taverns have been as much a part of American life as churches and preachers, or elections and politics." When Harvard University drew up its earliest plans in 1637, it included an on-campus brewery. Yet today, alcohol and its production, distribution, and consumption is one of the most strictly regulated industries in the United States.

Now that the COVID-19 pandemic has shut down the bars, taverns, and sunny brunch patios where Americans formerly imbibed with friends, many cities around the country have relaxed regulations related to alcohol service to help struggling restaurants and bars stay in business. California's Department of Alcoholic Beverage Control now allows take-out alcohol in conjunction with meals, alcohol delivery, and extended hours for retailers. These newly flexible rules on takeout booze and, to a certain extent, public drinking, raises the question: how and when did the U.S. start regulating alcohol sales and public drinking in the first place?

From Temperance to Prohibition

From the early days of the republic, Americans balked at alcohol taxation. In 1794, the Whiskey Rebellion erupted when farmers and distillers in Pennsylvania protested a federal excise tax on whiskey, leading to the downfall of Washington's Federalist party and the rise of the Republicans. However, aside from taxes, regulation on the sales and consumption of alcohol in public houses, restaurants, and stores didn't begin in earnest until the 19th century, when religious groups and grassroots women's organizations started sounding alarms about the social ills of drinking. In 1790, the average American consumed close to six gallons of alcohol per year. Consumption peaked in 1830 at seven gallons. This peak coincided with the beginning of the temperance movement and the association of drinking—and not just drunkenness—with immorality.

The modern temperance movement was formalized with the creation of the American Temperance Society in 1826. The Society was founded to convince people to abstain from drinking distilled beverages and grew to 1.5 million members over the next ten years. The mid-19th century saw the growth of several intertwined movements aimed at bettering society including the abolition of slavery, women's suffrage, labor rights, and temperance—movements which benefited from cross-pollination of ideas and tactics but sometimes came into conflict with one another.

The national movement coalesced around the Prohibition Party, which formed in 1869, and grew stronger with the fervent help of the Woman's Christian Temperance Union. Spearheaded by local WCTU activists, the temperance movement brought attention to the hardships and abuse experienced by the families of men who fell prey to the deprivations of alcoholism. The activists used slogans like "lips that touch liquor shall not touch ours" and associated drinking with violence, "moral degradation," and vice. In 1851, Maine became the first state to enact a ban on the sale of alcohol, a ban which was not fully repealed until after the passage of the 21st amendment in 1934. In 1862, the U.S. Navy abolished its daily rum ration, signaling a shift in how mainstream society viewed alcohol consumption.

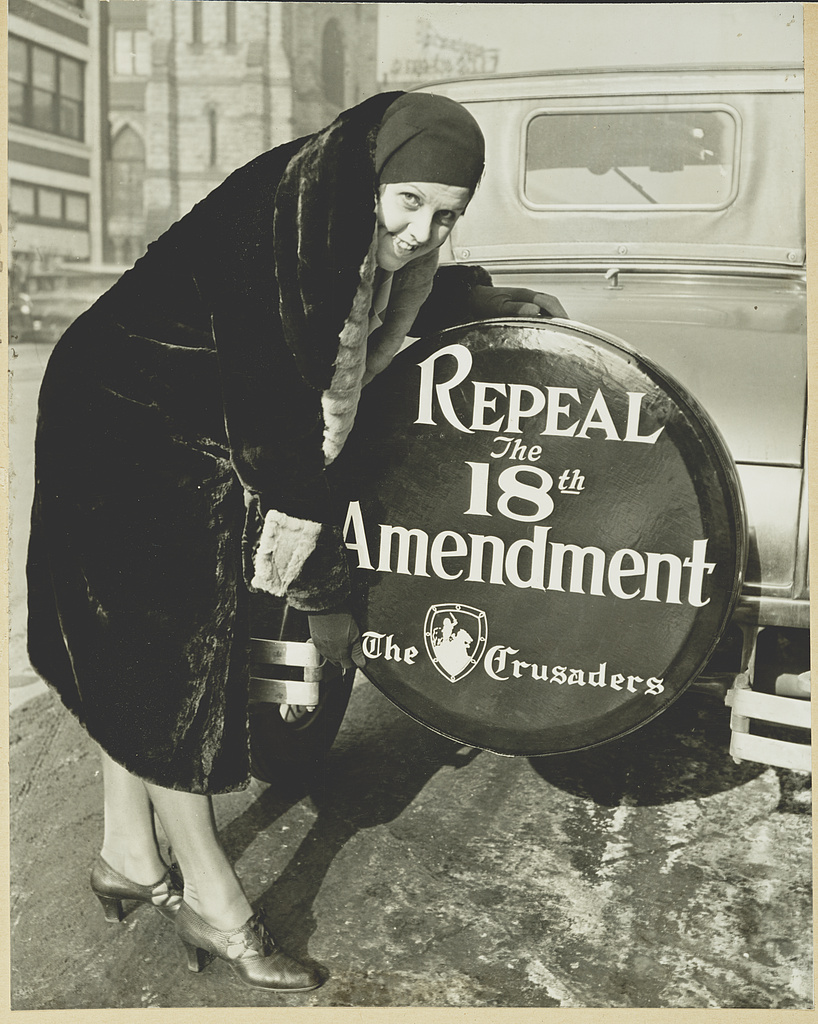

The fight for total prohibition swept the nation, with a congressional resolution for prohibition proposed in Congress in 1917. In 1919, the 36 required states ratified the 18th Amendment, prohibiting the sale of alcohol nationwide. Once passed, the Volstead Act banned the manufacture, sale, and transportation of "intoxicating substances" containing more than 0.5% alcohol by volume—meaning you could theoretically drink as much as you wanted to, provided the alcohol magically appeared in your hand with no visible means of transportation or production. The act also explicitly banned carrying containers of alcohol in the street, as this was considered transportation and implied an intent to sell.

The ban, predictably, drove drinking underground, both literally and metaphorically. Crime bosses jumped on the opportunity to import liquor from Canada and elsewhere and provide their wealthy patrons with an uninterrupted stream of booze at inflated prices. Prohibition arguably jumpstarted American organized crime and made the careers of some of history's most notorious gangsters. At the height of Prohibition, at least 30,000 speakeasies operated in New York City alone (with some estimates ranging as high as 100,000). In some western states, enforcement was practically impossible. Of course, as with many other things, Prohibition laws were applied unevenly, with the poor bearing the brunt of enforcement efforts.

It didn't take long for Prohibition to lose public support. The law did little to stem the flow of alcohol and decimated tax revenues. Even staunch Prohibition supporters became disillusioned with the open flouting of laws and the economic losses suffered with little positive result, and violent crime associated with bootlegging soared. A 1926 poll showed that 81% of Americans favored changing or repealing Prohibition. The stock market crash of 1929 and ensuing Great Depression put the final nail in the coffin of Prohibition as policymakers realized alcohol taxes could help prop up the crumbling economy, make up for lost income taxes, and create millions of jobs. The 18th Amendment was repealed in 1933.

Once federal alcohol legislation was struck down, states were free to make their own laws regarding alcohol production and consumption. Legalization, in many instances, made it more difficult to get a drink: with it also came regulations on hours, age requirements, and "blue laws." These regulations remain a jumbled patchwork of state and local ordinances today. Some counties are still "dry," and you couldn't buy alcohol by the glass in the state of Kansas until 1987.

Alcohol on Tribal Lands

Native American reservations have a largely different and unique history with alcohol legislation, much of which is entangled with their broader struggles to maintain autonomy in the face of the U.S. government. In 1802, President Jefferson requested federal legislation prohibiting alcohol on tribal lands. The resulting law allowed the President to control alcohol sales and distribution on tribal lands. In 1832, an updated law read, "no ardent spirits shall be hereafter introduced, under any pretense, into the Indian country." The law was accompanied by bans on the purchase and consumption of alcohol by Native Americans even off reservations, and such laws remained in place until 1953. Since then, the regulation of alcohol production and consumption have continued to cause controversy on tribal lands.

Drinking in the Public Realm

The act of drinking alcohol in public spaces wasn't regulated for the first two decades after the end of Prohibition. Then, in 1953, Chicago passed the country's first law against "drinking in the public way," aimed at giving law enforcement a reason to break up "bottle gangs," groups of indigent and working-class men who hung out on the city's streets, occasionally causing fights and leaving litter outside local businesses. Seven years later, the peace of Newport, Rhode Island was shattered as thousands of rowdy and drunk teenagers, eager to see jazz legends like Louis Armstrong and Dinah Washington perform at the city's legendary jazz festival, charged the event's gates and caused a massive riot that was eventually dispersed by the National Guard. The city, fearful of similar incidents, created a special ordinance banning drinking in public. After Newport, other popular youth destinations like Miami and Daytona Beach passed similar ordinances, hoping to preempt any unrest caused by the newly popular custom of Spring Break. Ordinances banning "public drunkenness" proliferated under the banner of public safety.

Unsurprisingly, these laws saw uneven enforcement and were often thinly veiled excuses to arrest the poor and people of color, particularly as vagrancy laws, which had previously been convenient tools for harassing the poor and indigent, began to face constitutional challenges. By the early 1960s, critics of public intoxication laws argued that they wasted law enforcement resources on non-violent offenders, targeted Black people, and criminalized addiction. In 1964, the Supreme Court struck down a California statute that criminalized drug addiction in Robinson v. California, paving the way to a reduction in the "status offenses" that criminalize a person's state of being rather than specific behavior. In 1971, the federal Uniform Alcoholism Treatment Act called on states to decriminalize public intoxication and shift the focus to public health rather than arrest and punishment.

By the early 1980s, courts had struck down most vagrancy laws, and cities looked for new ways to control public behavior, shifting the emphasis to visible drinking and "open containers." Dubious drinking restrictions persisted, and so did their racial and class connotations. When New York City outlawed open containers on its streets in 1979, a lawmaker told the New York Times, "we do not recklessly expect the police to give a summons to a Con Ed worker having a beer with his lunch. This is for those young hoodlums with wine bottles who harass our women and intimidate our senior citizens." Public drinking regulations, like vagrancy laws, are intended only for those groups viewed as threatening to the status quo, and continue to be enforced unequally. "Someone drinking a glass of wine on the stoop of their million-dollar Brooklyn brownstone is less likely to be called out than the people with the cooler of beers on the public beach."

Public drinking bans spread to most American cities, with the notable exceptions of New Orleans, the Las Vegas strip, Memphis's entertainment district, and other cities that depend on alcohol-related tourism such as Sonoma, California and Hood River, Oregon. Districts with permissive open container laws see them as a benefit to local economies, and a recent trend has seen more cities establish "entertainment districts" and other areas specifically designated for legal drinking. Residents of Erie, Pennsylvania, a Rust Belt town in transition to a 21st century economy, praise the city's lax open container laws as a boon to local businesses and events. Cincinnati, Bellevue, Kentucky, and even Manhattan have instituted policies that legalize or reduce penalties for public drinking in popular entertainment districts, pointing to an increased tolerance for alcohol in public spaces and a recognition of its economic benefits.

Last year, as the pandemic shuttered bars and restaurants for on-site dining, other cities emulated these policies as they quickly adjusted food and beverage service regulations to help struggling businesses stay afloat. Eateries shifted to a takeout-only model and started selling cocktails and beer to-go, and anecdotal evidence points to law enforcement turning a blind eye (albeit with similar racial biases as in the past) to alcohol consumption in parks and other public outdoor spaces where open containers might traditionally earn you a citation. Consumers and policymakers have already called for making some of the new regulations permanent.

As this history shows, U.S. public drinking laws have shifted repeatedly in response to circumstances and public opinion, and they're likely to continue evolving. As COVID-19 forces us to reevaluate how we utilize and engage with public space, institutionalizing recent changes beyond the pandemic has the potential to reinvigorate local economies and public spaces, reduce unjust arrests, and conserve public resources. Here’s to the next chapter in the story of public drinking in the United States.

Maui's Vacation Rental Debate Turns Ugly

Verbal attacks, misinformation campaigns and fistfights plague a high-stakes debate to convert thousands of vacation rentals into long-term housing.

Planetizen Federal Action Tracker

A weekly monitor of how Trump’s orders and actions are impacting planners and planning in America.

In Urban Planning, AI Prompting Could be the New Design Thinking

Creativity has long been key to great urban design. What if we see AI as our new creative partner?

King County Supportive Housing Program Offers Hope for Unhoused Residents

The county is taking a ‘Housing First’ approach that prioritizes getting people into housing, then offering wraparound supportive services.

Researchers Use AI to Get Clearer Picture of US Housing

Analysts are using artificial intelligence to supercharge their research by allowing them to comb through data faster. Though these AI tools can be error prone, they save time and housing researchers are optimistic about the future.

Making Shared Micromobility More Inclusive

Cities and shared mobility system operators can do more to include people with disabilities in planning and operations, per a new report.

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.

planning NEXT

Appalachian Highlands Housing Partners

Mpact (founded as Rail~Volution)

City of Camden Redevelopment Agency

City of Astoria

City of Portland

City of Laramie