Planners must work in diverse political environments including conservative jurisdictions that are skeptical of new issues and perspectives. Here are ways to reconcile conflicting goals.

Planners are change managers; it is our responsibility to identify and respond to evolving community needs. The Republication party that has taken over the U.S. federal government, plus many states and municipal governments, reflects a conservative ideology that tends to resist change. How can progressive planners work in this environment? Here are suggestions.

Progressive planners and ideological conservatives

Progressive planner refers to planners who try to respond to new goals and perspectives such as demographic changes, emerging risks, social equity, public health and safety, homelessness, and new transportation technologies, to name a few.

Ideological conservative refers to people who dislike social change. This term is a little ironic since conservative literally means being cautious and resource-efficient, which the current crop of ideological conservative often is not – they often oppose public health and safety initiatives such as pandemic restrictions and traffic safety initiatives, and resource conservation initiatives such as energy conservation and transportation demand management programs. The opposite of conservative is a liberal ideology. The following table compares their priorities.

Comparing Priorities

Conservative |

Liberal |

|

|

Conservatives and liberals have different but often overlapping priorities. Planners can help find areas of agreement and cooperation.

Although there are differences, there are also many areas of overlap among these priorities. Regardless of our personal priorities planners have a professional responsibility to help achieve all community goals and work with all community stakeholders. The following examples illustrate ways to do this.

Social equity

Social equity refers to the distribution of impacts (benefits and costs), and whether that is considered fair and appropriate. There are various types of equity to consider, as discussed in my reports Evaluating Transportation Equity and Fair Share Transportation Planning. The two major categories are horizontal equity (also called fairness), which considers how impacts are distributed between similar groups, and vertical equity (also called social justice) which considers how impacts are distributed between groups that differ in ability, need or income.

Types of Transportation Equity Analysis

Type |

Description |

|

Horizontal |

Similar people should be treated similarly |

|

Fair Share |

Each person receives a fair share of public resources. |

|

External costs |

Travellers minimize the costs they imposed on others. |

|

Vertical |

Public policies should favor disadvantaged groups |

|

Inclusivity |

Ensure that everybody enjoys basic mobility and accessibility. Reduce mobility disparities. |

|

Affordability |

Lower-income households can afford basic mobility. Provide affordable travel options. |

|

Social Justice |

Everybody is treated with fairness and dignity. Past injustices are corrected. |

There are various ways to evaluate transportation equity. Comprehensive analysis should consider multiple perspectives and priorities.

Conservatives tend to focus on fairness, for example, whether a jurisdiction or group receives a comparable share of public investments or bears a comparable share of costs. Liberals tend to focus on vertical equity, for example, whether disadvantaged groups receive a sufficient share of resources to meet their extra needs. As a result, liberal policies tend to be categorical: they favor groups that fit into special categories based on ability, income, gender and minority status (often referred to as Black, Indigenous and People of Color, or BIPOC). Ideological conservatives tend to find this unfair and unwieldy. For example, they question whether middle-income minorities should be favored over lower-income Whites, or whether able and affluent seniors should receive transit fare discounts while working-class families with children pay full fare. As a result, ideological conservatives tend to criticize categorical equity and favor functional equity analysis.

There are, of course, good reasons to apply categorical equity policies. Minority groups suffer from structural discrimination that harms them as individuals and groups. Researchers such as Robert Bollard show that minority communities experience environmental discrimination and harms at much higher rates than non-minority communities of comparable income. My report, Racism and Colonialism in Geography Textbooks, shows how anthropologists and geographers used pseudoscience to rate some races above others, leading to centuries of bias and discrimination. This research justifies targeted benefits to offset those injustices.

However, planners working in conservative jurisdictions may be more effective by applying functional rather than categorical equity solutions. There is significant overlap between these factors. For example, in liberal communities, sidewalk and public transit improvements can be prioritized based on minority household densities, but in conservative communities, those investments can be prioritized based on densities of people with disabilities, households with low incomes, children, and seniors; the results are often similar.

Consumer sovereignty

Consumer sovereignty refers to a market’s ability to respond to consumer demands. This helps increase efficiency and equity. For example, if many families want to live in walkable neighborhoods but cannot due to limited supply, as surveys indicate, consumer sovereignty justifies policies to create more housing options in existing walkable neighborhoods, and improve walkability in neighborhoods where walking is currently difficult and dangerous.

This concept tends to appeal to ideological conservatives. Conservatives may oppose Smart Growth policies if presented as a way to reduce climate emissions but support them if presented as a response to unmet demand for lower-cost housing in walkable neighborhoods. Similarly, conservatives may be persuaded to support more funding for sidewalks and bikeways to accommodate seniors and families with children, and serve growing e-bike travel demands. Progressive planners should collect demographic data, surveys and local anecdotes that indicate unmet demands for non-auto travel and affordable infill housing, and identify ways to provide them.

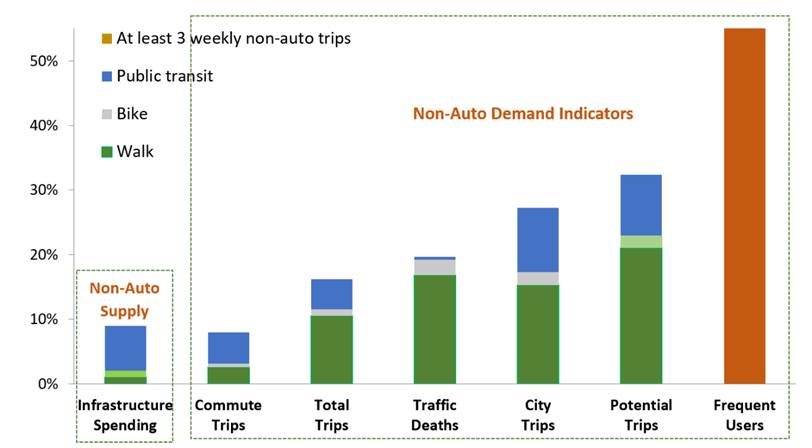

It is important to provide comprehensive demand data. Previously planners often used census commute mode share data to estimate travel demands. Measured this way, non-auto travel demand is tiny and unimportant, and requires minimal support. However, commute data undercount and undervalue walking and bicycling. More comprehensive surveys indicate that about 15 percent of U.S. trips are made by walking, bicycling and public transit, and the potential is higher. The study, The Multimodal Majority? Driving, Walking, Cycling, and Public Transportation Use Among American Adults, found that during a typical week about 7 percent of Americans rely entirely on non-auto modes, 65 percent use a non-auto mode one to five times, and 25 percent use a non-auto mode seven or more times. Use of these modes often increases significantly after their travel conditions are improved, indicating latent demands and benefits from those improvements.

Potential non-auto mode shares are much higher than what most North American communities spend on their infrastructure, as indicated below. This suggests that more investments in walking, bicycling, and public transit are justified for efficiency and fairness sake, arguments that can appeal to conservatives.

Non-Auto Spending Versus Demand Indicators

Most policymakers like to consider themselves advocates for their constituents, particularly disadvantaged groups, and they also like to propose clever solutions that stretch public dollars. Planners can help identify underserved groups and identify creative ways to meet their needs. For example, a progressive planner could help people with disabilities meet with policymakers to advocate for universal design standards, and identify new ways to fund sidewalk improvements so more of the community is accessible to everybody.

Rural community development

Rural communities tend to be ideologically conservative and have special needs, including high rates of poverty, disability, and isolation. Many rural seniors want better transportation and housing options so they can age in place, and rural youths want better bicycling and public transit for more independent mobility. Rural policymakers of all ideologies tend to recognize these needs and support rural multimodal planning, affordable housing development, and small-town revitalization. Progressive planners can support these strategies, showing how they respond to community needs.

One particularly important policy is to improve interregional bus services, which are important for non-drivers and rural communities. Currently, federal and state departments of transportation provide little support for such services, both conservatives and liberals have good reasons to fill this gap.

Sustainability

Many government agencies have sustainability goals and policies that encourage efficient transportation and compact development to reduce climate emissions. Conservatives may not prioritize that goal but support similar policies for other reasons. Progressive planners can identify win-win solutions that help achieve multiple goals and highlight those that resonate with various groups. For example, when speaking with conservatives show how multimodal transportation and compact development help increase affordability, fairness, infrastructure savings, and local economic development. When meeting with public health officials highlight health and safety benefits. When meeting with local business groups, highlight economic development and quality of life benefits. The following table summarizes the range of goals achieved by various transportation improvement strategies: improving efficient mode and compact development tend to achieve the greatest range of community goals.

Community Goals |

Roadway Expansion |

Efficient and Alt. Fuel Vehicles |

Efficient Modes and Compact Dev. |

Conservative Priorities |

|

|

|

|

Congestion reduction |

X |

|

X |

|

Roadway cost savings |

|

|

X |

|

Parking cost savings |

|

|

X |

|

Consumer savings and affordability |

|

|

X |

|

Traffic safety |

|

|

X |

|

Improved mobility options |

|

|

X |

|

Strategic development objectives |

|

|

X |

Liberal Priorities |

|

|

|

|

Consumer sovereignty |

|

|

X |

|

Energy conservation |

|

X |

X |

|

Pollution reduction |

|

X |

X |

|

Physical fitness and health |

|

|

X |

(X = Achieve objectives.) Roadway expansion and more efficient and alternative fueled vehicles provide few benefits. Win-Win Solutions that improve and encourage more efficient travel options and more compact urban development help achieve many planning objectives.

Summary of arguments

Below are perspectives and arguments that can be used to support more equitable planning in a politically conservative community:

- Basic mobility, and therefore more inclusive and affordable transportation planning, is critical to allow people, including those with disabilities and low incomes, to access education, employment, and other economic opportunities. It is a hand-up, not a handout.

- Improving non-auto travel expands the pool of potential employees and customers available to businesses, supporting economic opportunity to disadvantaged workers and economic development to communities.

- Improving and encouraging non-auto modes is often the most cost-effective way to reduce traffic congestion and parking problems, and therefore helps governments and businesses save money on road and parking infrastructure.

- Improving active modes improves public fitness and health, addressing health problems such as obesity and diabetes that plague many politically conservative regions.

- Improving non-auto modes can be an effective traffic safety strategy. Traffic safety strategies such as graduated driver’s licenses, special senior driver testing, and anti-impaired driving campaigns become more effective and politically acceptable if matched with improved travel options for youths, seniors, and drinkers.

- Upzoning to allow compact housing types in residential neighborhoods can increase affordability, reduce government costs, support local economic development, and allow residents to age in place.

- Surveys indicate that many households want to live in walkable neighborhoods, and many travelers would prefer to drive less and rely more on non-auto modes, provided that those options are convenient and affordable. Consumer sovereignty requires that public policies respond to those demands.

- More efficient transportation and parking management can reduce parking problems and impervious surface area and therefore stormwater management costs.

Progressive planners may be challenged to address changing community goals in ideologically-oriented communities, but this increases the need for our skills. What do you think? How can we best serve conservative communities?

For more information

AARP and CNU (2021), Enabling Better Places: A Handbook for Improved Neighborhoods, American Association of Retired Persons.

Kristin N. Agnello (2018), Zero to 100: Planning for an Aging Population, Plassurban.

Samikchhya Bhusal, Evelyn Blumenberg and Madeline Brozen (2021), Access to Opportunities Primer, UCLA Institute of Transportation Studies.

Ralph Buehler and Andra Hamre (2015), “The Multimodal Majority? Driving, Walking, Cycling, and Public Transportation Use Among American Adults,” Transportation 42, 1081–1101.

Michael Lewyn (2024), Project 2025 and Housing Policy: The Heritage Foundation has issued Project 2025, a list of policy proposals for the next Republican administration. On housing, it seems to embody a range of perspectives, Planetizen.

Fie Li and Christopher Kajetan Wyczalkowski (2023), “How Buses Alleviate Unemployment and Poverty: Lessons from a Natural Experiment in Clayton County, GA,” Urban Studies.

Todd Litman (2022), “Evaluating Transportation Equity: Guidance for Incorporating Distributional Impacts in Transport Planning,” ITE Journal, Vo. 92/4, April.

Todd Litman (2024), Fair Share Transportation Planning, Victoria Transport Policy Institute.

Todd Litman (2024), A Business Case for Improving Interregional Bus Services, Victoria Transport Policy Institute.

Opportunity Atlas measures economic opportunity for U.S. communities.

Marcelo Remond (2024), How Would Project 2025 Affect America’s Transportation System?, Planetizen

Transport Equity Analysis is a European Union program to provide practical guidelines for assessing the equity impacts of transportation projects and policies.

Maui's Vacation Rental Debate Turns Ugly

Verbal attacks, misinformation campaigns and fistfights plague a high-stakes debate to convert thousands of vacation rentals into long-term housing.

Planetizen Federal Action Tracker

A weekly monitor of how Trump’s orders and actions are impacting planners and planning in America.

In Urban Planning, AI Prompting Could be the New Design Thinking

Creativity has long been key to great urban design. What if we see AI as our new creative partner?

King County Supportive Housing Program Offers Hope for Unhoused Residents

The county is taking a ‘Housing First’ approach that prioritizes getting people into housing, then offering wraparound supportive services.

Researchers Use AI to Get Clearer Picture of US Housing

Analysts are using artificial intelligence to supercharge their research by allowing them to comb through data faster. Though these AI tools can be error prone, they save time and housing researchers are optimistic about the future.

Making Shared Micromobility More Inclusive

Cities and shared mobility system operators can do more to include people with disabilities in planning and operations, per a new report.

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.

planning NEXT

Appalachian Highlands Housing Partners

Mpact (founded as Rail~Volution)

City of Camden Redevelopment Agency

City of Astoria

City of Portland

City of Laramie