Many people assume incorrectly that motorists pay their share of roadway costs through fuel taxes. Not so. Fairness would require much higher motor vehicle user fees to finance roadways.

In Washington State there is a proposal to tax bicycles so that bicyclists help pay for the roads they use. On the other hand, there is considerable political resistance to increasing fuel taxes to offset inflation, or to charging road tolls or parking fees to cover facility costs. These are part of a larger debate concerning what is the most equitable way to finance transportation infrastructure.

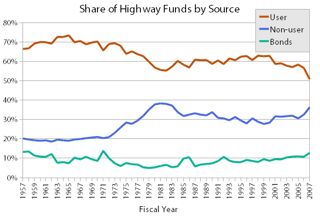

During most of the twentieth century, motor vehicle travel, and therefore fuel consumption, grew steadily so fuel tax revenue tended to increase from year to year. However, during the last decade, vehicle travel has peaked, vehicles have started to become more fuel efficient, and as a unit rather than a percentage tax, inflation reduces the value of fuel tax revenue, so real (inflation adjusted) fuel tax revenue is now declining. The portion of roadway expenses paid by user fees (special fuel and tire taxes, and road tolls) has declined in recent years, to less than half of roadway expenditures.

According to the study, Do Roads Pay For Themselves?, only about half of total roadway costs are financed by user fees.

According to the U.S. Government Transportation Financial Statistics 2012, Table 3.35, in 2009 (the most recent year reported), federal, state and local governments allocated $160 billion for roadway spending, about $533 per capita, of which about half is funded through user fees.

As a result, people who drive less than average tend to subsidize their neighbors who drive more than average. Somebody who never drives pays, on average, about $267 in annual general taxes to fund roadways. Highway cost allocation studies have estimated the roadway costs imposed by various types of vehicles. Although these studies focus on motor vehicle costs, this research indicates that these costs increase exponentially with vehicle size and weight, which indicates that cycling imposes very small costs, and since cyclists tend to travel fewer annual miles than motorists, bicyclists impose minimal roadway costs per capita.

These economic transfers are far greater if we also account for vehicle parking subsidies. A typical urban parking space has an annualized costs of $500 to $1,500, and there are an estimated two to six off-street parking spaces per motor vehicle. These costs mostly borne indirectly through rents and taxes. A typical motorist receives hundreds or thousands of dollars in annual parking subsidies. This only accounts for infrastructure costs. Motor vehicle travel also imposes delay (called the "barrier effect"), accident risk, and air pollution and noise impacts that motor vehicles impose on pedestrians and cyclists, external costs that can be considered a subsidy to driving.

Such subsidies are unfair and inefficient. Since vehicle ownership and use tend to increase with income, they are regressive, resulting in cross-subsidies from lower- to higher-income people, and they encourage travelers to drive more than is economically optimal, which increases traffic congestion, accidents, pollution emissions and sprawl.

There is a lot of hypocrisy on this issue. Highway advocates argue that "diverting" fuel tax revenue to supporting other modes, such as non-motorized and public transportation, based on horizontal equity, which implies that consumers should "get what they pay for and pay for what they get." But this principle also implies that motorists should pay all of the costs they impose, including all road and parking facilities, and other economic and environmental costs they impose on others. Highway advocates generally ignore this point.

The root of the problem is that automobile transportation is costly - more costly in total than other modes. Motorists spend, on average, about 18% of their income on their vehicles and fuel, and about 10% of their housing costs for residential parking. This heavy cost burden makes motorists selfish; they often argue that somebody else should bear the costs of road and parking facilities in order to make driving affordable, and that no transportation funds should be "diverted" to support other modes. As a result, alternatives are underfunded: although 10-15% of urban trips are made by walking and cycling, non-motorized modes only receive 1-3% of total transportation funding, and far less if parking facility costs are also considered. A better solution than increasing subsidies for driving is to invest more in affordable modes, particularly walking and cycling facilities, in order to reduce total transport costs.

For More Information

Joseph Henchman (2013), Gasoline Taxes and Tolls Pay for Only a Third of State & Local Road Spending, The Tax Foundation.

Edward Huang, Henry Lee, Grant Lovellette and Jose Gomez-Ibanez (2010), Transportation Revenue Options: Infrastructure, Emissions, and Congestion, Belfer Center, Harvard Kennedy School.

Todd Litman (1996), “Using Road Pricing Revenue: Economic Efficiency and Equity Considerations,” Transportation Research Record 1558, Transportation Research Board.

Todd Litman (2012), Whose Roads? Evaluating Bicyclists’ and Pedestrians’ Right to Use Public Roadways, VTPI.

Todd Litman (2013), Local Funding Options for Public Transportation, Paper 13-3125, Transportation Research Board 2013 Annual Meeting.

NSTIFC (2009), Paying Our Way: A New Framework Transportation Finance, Final Report of the National Surface Transportation Infrastructure Financing Commission.

Lisa Schweitzer and Brian Taylor (2008), “Just Pricing: The Distributional Effects Of Congestion Pricing And Sales Taxes,” Transportation, Vol. 35, No. 6, pp. 797–812.

Maui's Vacation Rental Debate Turns Ugly

Verbal attacks, misinformation campaigns and fistfights plague a high-stakes debate to convert thousands of vacation rentals into long-term housing.

Planetizen Federal Action Tracker

A weekly monitor of how Trump’s orders and actions are impacting planners and planning in America.

In Urban Planning, AI Prompting Could be the New Design Thinking

Creativity has long been key to great urban design. What if we see AI as our new creative partner?

King County Supportive Housing Program Offers Hope for Unhoused Residents

The county is taking a ‘Housing First’ approach that prioritizes getting people into housing, then offering wraparound supportive services.

Researchers Use AI to Get Clearer Picture of US Housing

Analysts are using artificial intelligence to supercharge their research by allowing them to comb through data faster. Though these AI tools can be error prone, they save time and housing researchers are optimistic about the future.

Making Shared Micromobility More Inclusive

Cities and shared mobility system operators can do more to include people with disabilities in planning and operations, per a new report.

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.

planning NEXT

Appalachian Highlands Housing Partners

Mpact (founded as Rail~Volution)

City of Camden Redevelopment Agency

City of Astoria

City of Portland

City of Laramie