A recent book brings a common sense framework to historic preservation debates.

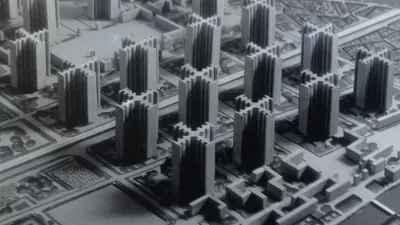

The role of historic preservation—or “heritage” as it's often termed overseas—is a conundrum faced regularly in the planning and development world. In rapidly changing cities with redevelopment incentives, "what to save" is front-page news, and the loss of special places is forever memorialized. I’ve often advocated getting down to the basics of why, in the digital age, lost or threatened buildings have moved from coffee table books to Instagram, amid nostalgia, gentrification challenges, and debates about the “authenticity” of façade-based urban cores.

In Why Old Places Matter (Rowman & Littlefield, 2018), Tom Mayes has gone even further, and summarized his years of work—and six months in Rome—devoted to answering that most basic question about the importance of places commonly perceived as "old." The book is a great read for built environment professionals, elected officials and others who work with urban issues. Mayes also provides a solid summary in many talks accessible online, including a recent talk in Providence, here.

In Why Old Places Matter (Rowman & Littlefield, 2018), Tom Mayes has gone even further, and summarized his years of work—and six months in Rome—devoted to answering that most basic question about the importance of places commonly perceived as "old." The book is a great read for built environment professionals, elected officials and others who work with urban issues. Mayes also provides a solid summary in many talks accessible online, including a recent talk in Providence, here.

In the book, Mayes has compiled and modified his previous essays of the same name, and he provides a range of thoughtful responses and research. Mixing personal anecdote with holistic thinking across the eras, he makes a convincing case, with a rich range of photographs, and provides the ultimate, pragmatic revelation: “old places are more important to people—and for more reasons—than I thought.”

Mayes, who is a colleague and collaborator, brings years of experience to the book as vice president and senior counsel at the National Trust for Historic Preservation, and from teaching preservation law. He summarizes fourteen reasons why retaining “old places” is important to people and their communities, including feelings of belonging, continuity, stability, identity and memory, as well as history, national identity, and architecture. His revelations are laden with common sense, and he is highly motivated to encourage discussion by establishing how these reasons resonate with his readers.

While Mayes does not hesitate to discuss the illuminating role of Presidents’ and authors’ houses, his explanations travel far beyond the United States and the narrow world of building preservation. He tells the story of Matera, in Basilicata, Italy, where poverty and disease necessitated new housing to replace ages-old sassi cave dwellings, but a sense of community was lost. He tells stories of continuity of building use, and changed attitudes about Confederate statues, including those in his own hometown. On a practical level, Mayes equates “old places” with today’s fascination with DNA tests, and ancestry websites.

The book is full of quotations and the prior work of others (and I’m grateful for references to my own books), but what I like best is the author’s voice as a fireside storyteller, providing accessibility to otherwise heady concepts. He explains how “time” is often left out of more modern movements such as “placemaking” or “new urbanism.” Old places, he notes, already have, for example, walkability and public space, and have achieved the marriage of people, place and time to form and foster community and sustainability.

Mayes also succeeds as a solid communicator of the concept of “age-value,” a term more prevalent in Europe than the United States, but in my opinion critical to balanced urban development going forward. Both Miles Glendinning, The Conservation Movement: A Cult of the Modern Age (Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, 2013) and Alois Riegl, The modern cult of monuments: its character and its origins (MIT Press, 1982), speculate on the popularization of heritage in western culture. Like Mayes, they present historic significance as attachment (often forgotten over time) between objects, spaces and people. Riegl argues that urban memory is the main idea behind claims of “authenticity.” Riegl’s “age-value” term reveals the impact of the transition often witnessed by the authors in westernized urban space: replacing original artwork on the street with replicas or symbols of what came before.

For those seeking outright practicality, Mayes’ final full chapter speaks to multiple reasons why old places also foster sustainable economies, and his concluding comments speak to new research and new technologies. This is not a book solely for antiquarians, nor limited to the museum house set. Rather, it is simply a delightful read, one that planners and peer professionals should take the time to digest for themselves.

As Mayes summarizes his interview with Juhani Pallasmaa, a noted Finnish architect, “if we can see the past, it makes us believe in the future.”

Why Old Places Matter is available on Amazon in hardcover and Kindle formats, here, with much background available online as linked above.

Planetizen Federal Action Tracker

A weekly monitor of how Trump’s orders and actions are impacting planners and planning in America.

Maui's Vacation Rental Debate Turns Ugly

Verbal attacks, misinformation campaigns and fistfights plague a high-stakes debate to convert thousands of vacation rentals into long-term housing.

San Francisco Suspends Traffic Calming Amidst Record Deaths

Citing “a challenging fiscal landscape,” the city will cease the program on the heels of 42 traffic deaths, including 24 pedestrians.

Amtrak Rolls Out New Orleans to Alabama “Mardi Gras” Train

The new service will operate morning and evening departures between Mobile and New Orleans.

The Subversive Car-Free Guide to Trump's Great American Road Trip

Car-free ways to access Chicagoland’s best tourist attractions.

San Antonio and Austin are Fusing Into one Massive Megaregion

The region spanning the two central Texas cities is growing fast, posing challenges for local infrastructure and water supplies.

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.

Heyer Gruel & Associates PA

JM Goldson LLC

Custer County Colorado

City of Camden Redevelopment Agency

City of Astoria

Transportation Research & Education Center (TREC) at Portland State University

Jefferson Parish Government

Camden Redevelopment Agency

City of Claremont