Over the past few years a variety of documents ranging from contemporary media to more serious research efforts have addressed the cost of auto ownership and use. These estimates are often used to address two important transportation issues, the household benefits of using transit in lieu of auto ownership and/or the consideration of household location decisions in the context of the total cost of housing and transportation. Two often referenced sources of research on these issues are the Center for Neighborhood Technology’s (CNT) initiatives in developing a housing and transportatio

Over the past few years a variety of documents ranging from

contemporary media to more serious research efforts have addressed the cost of

auto ownership and use. These estimates

are often used to address two important transportation issues, the household

benefits of using transit in lieu of auto ownership and/or the consideration of

household location decisions in the context of the total cost of housing and

transportation. Two often referenced sources of research on

these issues are the Center for Neighborhood Technology's (CNT) initiatives in

developing a housing and transportation affordability Index and the AAA updates

on auto operating cost estimates[i]. These initiatives are noble efforts in our

march toward holistic thinking about transportation and transportation policy. Transportation costs – both financial and

others – are important considerations in both household decisions and

infrastructure planning and investment policy decisions.

While estimating vehicle ownership and use costs can be of value

in making decision makers – including individual travelers – aware of

transportation costs that might otherwise not be transparent or accurately

perceived, there are some risks associated with failing to more carefully

explore the various estimates of transportation costs. Citing something a lot does not automatically

make it true or the most appropriate piece of information to use.

The CNT transportation cost estimates are based on a

model that produces household transportation costs for major metro areas in the

US with estimated values typically ranging from just over $10,000 to in excess

of $15,000 for personal vehicle ownership costs per household per year. Alternatively, the Bureau of Labor Statistics

Consumer Expenditure Survey estimates national average household spending on

transportation to be under $8,000 per year. And as anyone knows from driving down a

residential street in America and in talking to their friends and neighbors,

the vehicle transportation spending varies dramatically based on travel levels

and consumer tastes and priorities as it relates to vehicle investment and use. The

AAA produces their annual "Your Driving Costs" which

produces an annually updated cost of vehicle ownership based on a five year

ownership period and 15,000 mile per year travel rate and produces an annual

cost of $8,946 or $0.596 per mile for 2012[ii]. The IRS allowed $0.555 per mile for business

use of personal vehicles in the second half of 2011.

Using the newest Consumer Expenditure Survey (CES) data from

2010, the average US household is reported to spend $7,667 per year on all travel

of which $7,184 per year is attributed to vehicle travel[iii]. Based on national household travel survey

data from 2008 – 2009, the average household had 2.1 vehicles, each of which

was driven approximately 9,460 miles annually[iv]. This data produces an estimated per mile

vehicle ownership and operating cost of approximately $0.36. If divided by an average occupancy of 1.67 it

results in an approximate $0.22 per passenger mile expenditure.

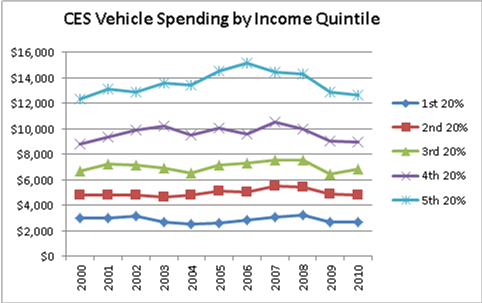

Figure 1 shows the spending trend on vehicle travel by

income quintile from Consumer Expenditure Survey data. Costs aren't particularly high and are not

growing – actually shrinking if adjusted for inflation - in spite of generally

rising fuel and vehicle costs[v].

The disparity between various high estimates of auto

ownership and operating costs and the measured average captured by the Consumer

Expenditure Survey partially lies in the very meaningful differences between

new car ownership and the reality that much of America isn't driving new cars

with high depreciation levels. Average

vehicle retention has increased to 71 months meaning that households are

retaining vehicles nearly 6 years, a trend attributed to both longer financing

terms and longer warrantees and improved vehicle reliability. The average age of autos has reached a record

high 10.8 years as of July 2011.[vi] In the U.S. light vehicles were noted in a

2006 study to be nearly 18 years old with approximately 170,000 miles on them

when they were scrapped on average[vii]. Depreciation costs become insignificant at

some point.

It's easy to see how ownership cost get quite high

with luxury and near luxury vehicle leases running above $500 per month plus equity

investment, insurance, gas, parking, etc. and it's not hard to imagine cost per

vehicle at or above the kinds of numbers cited by CNT or AAA. On the other hand, the young person or low

income worker who is driving aunt Martha's hand-me-down 14-year-old Ford or

Toyota that they purchased for a few hundred dollars, maintain in their driveway,

and drive with minimal insurance if any (various estimates suggest that as many

as 30% of vehicles do not have automobile insurance) might be defining the

other end of the household vehicle travel expenditure range[viii].

Unless one chooses not to believe the Consumer

Expenditure Survey data, Middle America has managed to control personal vehicle

expenditure costs making personal mobility surprisingly inexpensive. While this ignores the indirect costs and

perhaps understates other costs (arguably we are under investing in

transportation infrastructure and recent evidence suggests we've been

depreciating our vehicle fleet asset as well) and there seems to be an

increasing trend to use general revenue streams such as impact fees and

property taxes to support transportation infrastructure, thus leaving some

costs out of vehicle ownership and use cost estimates. But consumers are likely to make

economic decisions based on the direct costs that they bear.

So what does this all mean in terms of transportation policy

and planning? Clearly, many American

consumers of travel are not basing their travel decisions on vehicle ownership

and use costs that are nearly as high as those referenced in various resources and

research reports- several of which reflect an advocacy perspective. Take for example somebody seriously thinking

about using transit and perhaps giving up a household vehicle. In all probability they would be giving up a

lower cost/value vehicle – perhaps one that was fully depreciated or needed to

be replaced. There would be some savings

in operating cost but a significant share of the household mileage would likely

be shifted to the remaining household vehicles with increases in their

operating costs and depreciation rate. Persons

sensitive to travel costs who might be considering this decision are likely to

be individuals in low to moderate income categories where their household

spending on vehicle travel might be below or well below the mean levels of the

total population. Interestingly,

consumer expenditure data also show that even zero-vehicle households have

significant spending on vehicle travel. Giving

up or not purchasing a household vehicle is more likely to result in the use of

rental and/or borrowed vehicles or providing gas money to friends and family

for providing trips. Thus, presumptions

about total savings from relinquishing a vehicle need to reflect the full reality

of how travelers are behaving.

Data indicate that consumers have made decisions to reduce

auto ownership – or the economy has made it for them. Auto ownership levels have declined. While stories about home foreclosures are

regular headlines, less noticed is the reduction in personal vehicle ownership

from approximately 236 to 230 million registered vehicles nationally between

2008 and 2010[ix].

Assumptions about travel cost savings associated with

various residential location choices also require review relative to other

sources of household spending on travel. Again, there can be large variations in

context. For example, 27.2% of US

households have no workers in them – thus, their household travel costs can be

more controlled by their own choice decisions regarding trip destinations for

their travel. Another few percent (and

growing) have work-at-home members of the labor force. Unfortunately, fixed costs associated with

relocating a household particularly for home owning households, make

optimization of household location with respect to employment or travel generally

an unpromising proposition in an era of job mobility, multi-worker households, upside

down home-equity, and significant home purchase/sale transactions costs. However, recent data suggest a decline in

homeownership – while a consequence of the economic conditions, this perhaps provides

an opportunity to enable more households to more easily minimize commuting

costs[x].

While pointing out potential auto operating savings might be

an appropriate strategy for an advocacy entity, serious policy deliberations

are misinformed if they don't use a far more nuanced and empirically based set

of data on household travel expenditures and travel behavior as well as recognizing

the full costs of accommodating the changes in behavior, be they increased

transit demand and the corresponding costs or changes in population and employment

location preferences.

Consumers are generally rational creatures making what in

their eyes are sound decisions on spending.

It is important that planners and policy makers appreciate the revealed behavior

of various segments of the population when they make their location, vehicle

ownership, and mode choice decisions. Travel

costs are a factor in vehicle ownership, mode choice and household location

decision-making, but perhaps these costs are not well represented by the

savings potential that some analyses are implying or contending.

[viii]

LOWER-INCOME HOUSEHOLDS AND THE

AUTO INSURANCE MARKETPLACE: CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES, Stephen Brobeck and J. Robert

Hunter, January 30, 2012, http://www.consumerfed.org/news/450

[x] Home

ownership dropped from 68 to 62 percent from 2011 to 2012, according to an

April 2012 Gallup Survey. http://www.gallup.com/poll/154124/U.S.-Homeownership-Hits-Decade-Low.aspx

Maui's Vacation Rental Debate Turns Ugly

Verbal attacks, misinformation campaigns and fistfights plague a high-stakes debate to convert thousands of vacation rentals into long-term housing.

Planetizen Federal Action Tracker

A weekly monitor of how Trump’s orders and actions are impacting planners and planning in America.

San Francisco Suspends Traffic Calming Amidst Record Deaths

Citing “a challenging fiscal landscape,” the city will cease the program on the heels of 42 traffic deaths, including 24 pedestrians.

Defunct Pittsburgh Power Plant to Become Residential Tower

A decommissioned steam heat plant will be redeveloped into almost 100 affordable housing units.

Trump Prompts Restructuring of Transportation Research Board in “Unprecedented Overreach”

The TRB has eliminated more than half of its committees including those focused on climate, equity, and cities.

Amtrak Rolls Out New Orleans to Alabama “Mardi Gras” Train

The new service will operate morning and evening departures between Mobile and New Orleans.

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.

Heyer Gruel & Associates PA

JM Goldson LLC

Custer County Colorado

City of Camden Redevelopment Agency

City of Astoria

Transportation Research & Education Center (TREC) at Portland State University

Jefferson Parish Government

Camden Redevelopment Agency

City of Claremont