As I write this column (2 February) the U.S. House Transportation Committee is debating changes in H.R. 3864, the American Energy and Infrastructure Jobs Act, which will determine future federal transportation policy.

As I write this column (2 February) the U.S. House Transportation Committee is debating changes in H.R. 3864, the American Energy and Infrastructure Jobs Act, which will determine future federal transportation policy. The current version significantly reduces support for walking, cycling, public transport and transportation demand management. For example, it would eliminate funding for Transportation Enhancements and Safe Routes to School, significantly reduce federal public transport funding, and gives priority to congestion reduction over air pollution reductions in the Congestion Mitigation and Air Quality (CMAQ) funding program.

This is part of a general debate concerning strategic transport policy directions that affects many planning decisions including roadway design, land use development, local and regional transport plans, and state and federal legislation.

Much of this debate is political and ideological, pitting organizations that support multi-modal transport planning, such as the Rails To Trails Conservancy and public health advocates, against major industry and ideological organizations that favor automobile-oriented transport planning, such as the American Trucking Association and the Reason Foundation. Since this is sure to be an on-going discussion, let's consider these issues from a planning perspective.

The House bill reflects the older transport planning paradigm, which assumes that transportation means driving, so transport problem refers to constraints on driving and transport improvement refers to reducing constraints on driving. The new transport planning paradigm recognizes that mobility is seldom an end in itself: the ultimate goal of most transport activity is accessibility(people's ability to reach desired goods, services and activities), that mobility is just one factor affecting accessibility, that transport planning often involves trade-offs between different forms of accessibility (for example, expanding roads and increasing parking requirements in development codes tends to improve automobile accessibility but tends to reduce accessibility by walking, cycling and public transport), and that an efficient transport system is multi-modal, encouraging travelers to use each mode for what it does best: walking and cycling for short trips, ridesharing and public transport for travel on congested urban corridors, and automobile travel when it is truly most efficient overall, taking into account all impacts.

As discussed in a previous column, current demographic and economic trends are reducing growth in automobile travel demand – in fact, per capita VMT peaked about the year 2000, and total VMT peaked in 2007 in the U.S. (see graph below) and most other developed countries, while demand for transport alternatives is expected to increase due to aging population, rising future fuel prices, increased environmental and health concerns, and changing consumer preferences. During the last century, when vehicle ownership and use grew steadily, it made sense to invest significant resources to expand road and parking facilities, but that is no longer justified. It now makes sense to respond to changing demands by shifting resources to create a more diverse and resource-efficient transport system.

Although some of us may be healthy and wealthy into our old age, it is good to prepare for the worst, which may include physical disability, poverty or much higher fuel prices that require us to drive less and rely more on alternative modes. It makes sense to improve transport options in response to these changing demands and future uncertainties.

Are walking and cycling significant forms of transport deserving of federal support? It depends on how they are measured. Older transport surveys, and often-used statistics such as Census commute more share, generally indicate that non-motorized modes represent just a few percent of total travel, but these statistics tend to undercount walking and cycling because they often exclude short trips, non-commute travel, recreational travel, and travel by children. More comprehensive surveys indicate that walking and cycling represent 10-15% of total trips, and a much higher share in large cities. Unfortunately, non-motorized modes receive far less than that share of transportation funding, typically less than 2% of federal and state funds.

Similarly, conventional planning tends to undervalue public transport benefits by focusing on a limited set of impacts and objectives (for example, parking cost savings, and public safety and health benefits are often overlooked), and because conventional models tend to undervalue the congestion reduction benefits of high quality public transport.

Critics argue that walking, cycling and public tranpsort are local modes which should be planned and financed at the local level; the federal government should focus on intercity travel. That argument is silly, however, since a significant portion of traffic on federally-funded highways is local. That is not accidental, much of the "Interstate" highway system is in urban areas designed to accommodate local trips (my father commuted every day on Interstate 604 in Los Angeles), and improving alternative modes can help improve the performance of these facilities.

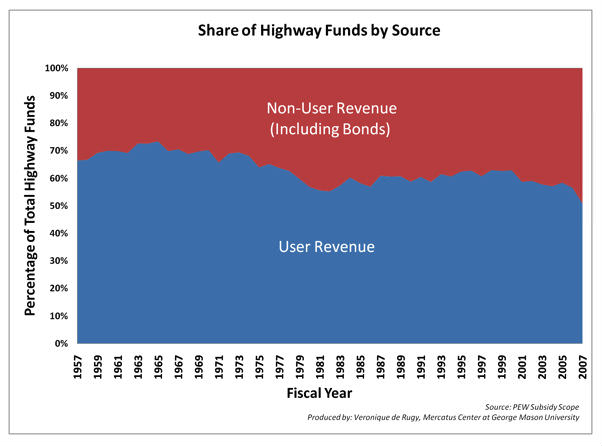

The main argument for reducing alternative mode funding is that most of the transportation funds are generated by vehicle registration fees and fuel taxes, so it is unfair to divert these funds to other uses, assuming that consumers should get what they pay for and pay for what they get. But this argument is applied inconsistency: if fairness requires that they money paid by motorists be spent on their facilities fairness also requires that all roadway costs be borne by motorists. In fact, less than half of roadway costs and only a tiny portion of non-residential parking facility costs are financed by motorists' user fees. Spending motor vehicle user revenues to improve walking, cycling and public transport benefits motorists directly by reducing their traffic and parking congestion and reducing their chauffeuring burdens, and helps offset some of their road and parking subsidies.

Advocates of automobile-oriented planning claim that increasing motor vehicle travel is essential to support economic development. My research and recent research by Oregon State University researchers B. Starr McMullen and Nathan Eckstein indicates otherwise. In the future, as petroleum costs rise, energy conservation will probably provide even greater economic benefits. It therefore makes sense to implement policies now that help create a more energy efficient transport system in the future.

What do you think? Have I overlooked any important issue or perspective in this debate? How can planners help public officials develop transport policies that best meet future needs? Should they be more multi-modal? If so, why and how?

For More Information

Jeffrey R. Brown, Eric A. Morris and Brian D. Taylor (2009), "Paved With Good Intentions: Fiscal Politics, Freeways, and the 20th Century American City," Access 35 (www.uctc.net), Fall 2009, pp. 30-37; at www.uctc.net/access/35/access35.shtml.

Phil Goodwin (2011), "Peak Car: Evidence Indicates That Private Car Use May Have Peaked And Be On The Decline," Urban Intelligence Network (www.rudi.net/node/22123 ).

Peter L. Jacobsen, F. Racioppi and H. Rutter (2009), "Who Owns The Roads? How Motorised Traffic Discourages Walking And Bicycling," Injury Prevention, Vol. 15, Issue 6, pp. 369-373; http://injuryprevention.bmj.com/content/15/6/369.full.html.

Santhosh Kodukula (2011), Raising Automobile Dependency: How to Break the Trend? GIZ Sustainable Urban Transport Project (www.sutp.org); at www.sutp.org/dn.php?file=TD-RAD-EN.pdf.

John LaPlante (2010), "The Challenge of Multimodalism; Theodore M. Matson Memorial Award," ITE Journal (www.ite.org), Vol. 80, No. 10, October, pp. 20-23; at www.ite.org/membersonly/itejournal/pdf/2010/JB10JA20.pdf.

Todd Litman (2005), "Changing Travel Demand: Implications for Transport Planning," ITE Journal, Vol. 76, No. 9, September, pp. 27-33; at www.vtpi.org/future.pdf .

Todd Litman (2008), Introduction to Multi-Modal Transport Planning, VTPI (www.vtpi.org); at www.vtpi.org/multimodal_planning.pdf. Todd Litman (2011), The Value of Transportation Enhancements; Or, Are Walking and Cycling Really Transportation?, Planetizen (http://www.planetizen.com/node/52501).

David Metz (2010), "Saturation of Demand for Daily Travel," Transport Reviews, Vol. 30, Is. 5, pp. 659 – 674; summary at www.ucl.ac.uk/news/news-articles/1006/10060306 and www.eutransportghg2050.eu/cms/assets/Metz-Brussels-2-10.pdf.

John Poorman (2005), "A Holistic Transportation Planning Framework For Management And Operations," ITE Journal, Vol. 75, No. 5 (www.ite.org), May 2005, pp. 28-32; at www.ite.org/membersonly/itejournal/pdf/2005/JB05EA28.pdf.

Peter Samuel and Todd Litman (2001), "Optimal Level of Automobile Dependency; A TQ Point/Counterpoint Exchange with Peter Samuel and Todd Litman," Transportation Quarterly, Vol. 55, No. 1, Winter 2000, pp. 5-32; at www.vtpi.org/OLOD_TQ_2001.pdf.

Clark Williams-Derry (2011), "Dude, Where Are My Cars?", Sightline Institute (http://daily.sightline.org/blog_series/dude-where-are-my-cars ).

Maui's Vacation Rental Debate Turns Ugly

Verbal attacks, misinformation campaigns and fistfights plague a high-stakes debate to convert thousands of vacation rentals into long-term housing.

Planetizen Federal Action Tracker

A weekly monitor of how Trump’s orders and actions are impacting planners and planning in America.

San Francisco Suspends Traffic Calming Amidst Record Deaths

Citing “a challenging fiscal landscape,” the city will cease the program on the heels of 42 traffic deaths, including 24 pedestrians.

Defunct Pittsburgh Power Plant to Become Residential Tower

A decommissioned steam heat plant will be redeveloped into almost 100 affordable housing units.

Trump Prompts Restructuring of Transportation Research Board in “Unprecedented Overreach”

The TRB has eliminated more than half of its committees including those focused on climate, equity, and cities.

Amtrak Rolls Out New Orleans to Alabama “Mardi Gras” Train

The new service will operate morning and evening departures between Mobile and New Orleans.

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.

Heyer Gruel & Associates PA

JM Goldson LLC

Custer County Colorado

City of Camden Redevelopment Agency

City of Astoria

Transportation Research & Education Center (TREC) at Portland State University

Jefferson Parish Government

Camden Redevelopment Agency

City of Claremont