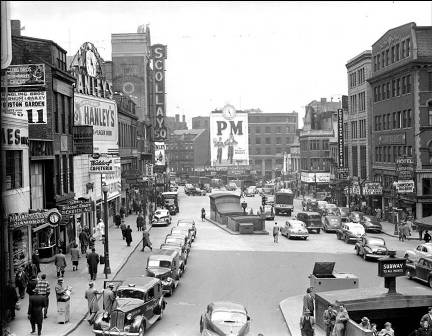

At a company presentation about environmental impact the other week a colleague included a historic photograph of Scollay Square in Boston. You are pardoned if, even after visiting or living in that city, this doesn’t sound familiar because all prominent characteristics of the area were summarily obliterated in the mid-twentieth century to make way for a potpourri of brutalist-style administrative buildings and renamed Government Center. Urban redevelopment arguments aside, the photograph reveals a particularly interesting detail about the function and use of streets virtually erased from our minds over the last century.

At a company presentation about environmental impact the other week a colleague included a historic photograph of Scollay Square in Boston. You are pardoned if, even after visiting or living in that city, this doesn't sound familiar because all prominent characteristics of the area were summarily obliterated in the mid-twentieth century to make way for a potpourri of brutalist-style administrative buildings and renamed Government Center. Urban redevelopment arguments aside, the photograph reveals a particularly interesting detail about the function and use of streets virtually erased from our minds over the last century.

In the center and bottom-right corner of the scene are subway headhouses, smack-dab in the middle of the street. Although Scollay Square is full of cars in this photo, it is clear that the configuration allows, or more accurately expects people to walk in and along the street to access the subway. Several people can be seen in the middle of the street, unencumbered by crosswalks, pedestrian signals, or medians. This is not a glimpse of utopia, but it certainly demonstrates that the street was once seen as a space for all users, not just for cars. As is the case with many of the contemporary trends in urban land use, the current call for returning to a streetspace environment where the public right-of-way is shared by multiple users is not a new idea. On the contrary, we have only just managed to forget the learned wisdom of thousands of years of urbanity in the Orweillian twilight of a car-culture gone awry. Photos like these, like Winston Smith's glass-encased tidbit of coral, tell of a different and friendlier world.

To be fair, one could make the claim that the photo also shows the natural tendency of pedestrians to keep to the sidewalk. True, but I submit that this is the effect of several causes that developed over a period of centuries. First, people tend to gravitate towards the attractive features of storefronts. Second, people tend to gravitate towards people. Third, the faster speed and larger size of horses, horse and buggy carriages, and eventually automobiles gradually pushed pedestrians towards the periphery of streets. Finally, the European design solution for rain and wastewater runoff (think bedpans emptied out of bedroom windows and horses in the hundreds) was the gutter, whereby the raised curb system used to whisk away water and waste resulted in a clean, elevated platform for pedestrians free of mud and puddles, and close to building fronts where there was also often shelter from rain. This last cause can be contrasted against the drainage solution often seen in many Japanese cities where a small channel is provided right in front of the storefront, and a short platform is used to bridge the gap between street and doorway. This alternate design results in a de facto shared street that freely mixes cars and pedestrians in even the most luxurious fashion, such as in Tokyo's glitzy Ginza district (see photo below).

In other words, the function of a sidewalk evolved out of various converging factors unrelated to an explicit attempt to create separate spaces for walking and driving. The domination of the street by cars in the last century is at least partially a result of an innocent tendency of pedestrians to traffic the sidewalk for various reasons, rather than a categorical forfeit of the majority of the public realm to one user-type. In the current, thrilling campaign by planners to return urbanity to something more human scale, a photo memorializing the multiplicitous modal functionality of Scollay Square before its razing is as good a symbol as any for wisdom that must be embraced once again.

Planetizen Federal Action Tracker

A weekly monitor of how Trump’s orders and actions are impacting planners and planning in America.

Chicago’s Ghost Rails

Just beneath the surface of the modern city lie the remnants of its expansive early 20th-century streetcar system.

San Antonio and Austin are Fusing Into one Massive Megaregion

The region spanning the two central Texas cities is growing fast, posing challenges for local infrastructure and water supplies.

Since Zion's Shuttles Went Electric “The Smog is Gone”

Visitors to Zion National Park can enjoy the canyon via the nation’s first fully electric park shuttle system.

Trump Distributing DOT Safety Funds at 1/10 Rate of Biden

Funds for Safe Streets and other transportation safety and equity programs are being held up by administrative reviews and conflicts with the Trump administration’s priorities.

German Cities Subsidize Taxis for Women Amid Wave of Violence

Free or low-cost taxi rides can help women navigate cities more safely, but critics say the programs don't address the root causes of violence against women.

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.

planning NEXT

Appalachian Highlands Housing Partners

Mpact (founded as Rail~Volution)

City of Camden Redevelopment Agency

City of Astoria

City of Portland

City of Laramie