In a history of the skid rows in American cities from the late 19th century until the urban renewal era of the 1960s, Ella Howard tells of the impoverished people who inhabited them and the policy choices that supported their existence.

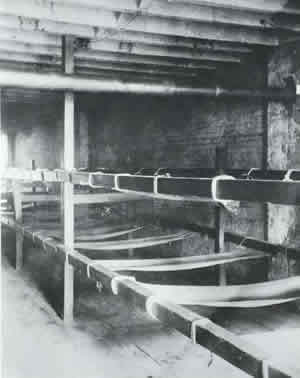

Ella Howard opens her study of the politics of homelessness, the experience of the homeless, and the skid rows they inhabited, Homeless: Poverty and Place in Urban America (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013), by telling of New York City Mayor Robert Wagner’s 1961 announcement of a redevelopment plan for the Bowery, Manhattan’s skid row. The plan was to renew the people and to reclaim the valuable central city land being used for single room occupancy hotels, dive bars, religious missions, low-cost restaurants, and public shelters. Howard focuses on the Bowery and uses historic photos of the living conditions there, such as the Jacob Riis image of a lodging house below, but her work is relevant to the many skid rows housing migrant workers and unemployed men that existed in American cities from the late 19th century to the post-World War II era of urban renewal.

Center city land became too valuable to remain as slum quarters for the impoverished; finding higher income producing uses for the land was easier than transforming the down-and-out into the productively employed. Today, the number of unsheltered persons is growing, but they no longer have the modest spheres afforded by downtown precincts with rudimentary supports. Howard uses the image below to show that some of the Bowery lodging houses included spaces where men could sit and pass their days in company.

In telling the story of poverty and place, Howard cites Kenneth L. Kusmer's Down and Out, On the Road: The Homeless in American History (Oxford University Press, 2003). Known as the "wandering poor," "sturdy beggars," or just as vagrants, they have been a part of the American landscape since colonial times when the unemployed and those displaced by war or natural disasters congregated in urban seaports. Howard describes the nation’s growing industrial cities of the 19th century as segregated by class, race, and ethnicity, with skid rows hiding the impoverished from society and allowing them to be considered the "other," undeserving of respect, regard, and social supports.

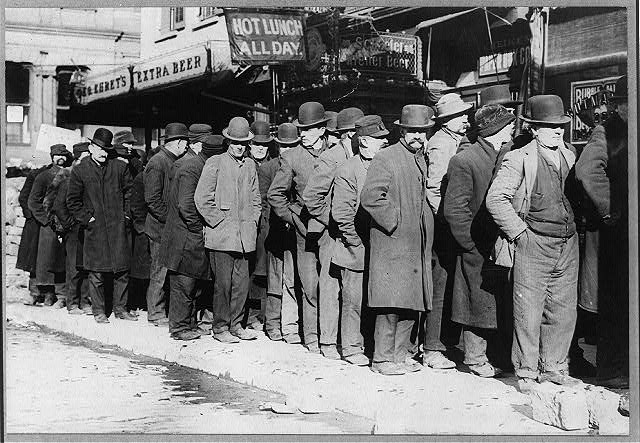

Ethnic and religious associations and a few public organizations offered succor until the Great Depression swelled the numbers of the poor far beyond the capacity of existing programs. National, state, and local governments were shocked into action by seemingly endless food lines, squatter shacks in public parks, hordes of beggars, and marching protesters. Many local and state officials refused to provide aid to those considered transients. While the numbers of impoverished and the presence of women and families among them forced public acknowledgement of their need, policies continued to focus on place—residency requirements for aid excluded persons who could not prove they belonged in the city. Howard shares an iconic Dorothea Lange image, “On U.S. 99. Near Brawley, Imperial County,” of a homeless mother and her youngest child of seven walking the highway from Phoenix, Arizona where they picked cotton, to San Diego, where the father ‘hopes to get on relief because he once lived there.’” The issue of what level of government and which local governments should be responsible for homeless persons continues to this day. Many local citizens insist that the indigent persons camped on their streets arrived from other places in search of generous handouts. Yet, many persons were already in a given community when they became homeless. (link to http://www.sfgate.com/bayarea/article/What-San-Franciscans-know-about-h…)

In the post-World War II era of prosperity, homeless declined in number, but faced additional stigmas. Howard describes the reaction of Michael Harrington, an activist who wrote of the Bowery's residents as suffering "the bitterest, most physical and obvious poverty that can be seen in an American city." In the midst of plenty, the homeless were considered to be sick. Rather than acknowledging the shortcomings of an economic structure that rewarded winners with prosperity and consigned losers to impoverishment, aid for the homeless consisted of efforts to reform their behavior, especially their drinking behavior. With fewer on skid row and those few considered capable of employment, potential for developing increasingly valuable center city real estate was enticing and could be supported by federal urban renewal money. Skid rows were replaced by commercial properties, the homeless scattered throughout downtowns, and proposals to create supportive housing were rejected in favor of returning the homeless to “normal” living. While social scientists looked for causes of poverty in choices made by individuals, other causes such as a decline in living wage jobs for unskilled workers, racism, sexism, homophobia, and unaffordable housing were not investigated.

Efforts to address individual behavior while ignoring social and economic context included local ordinances that prohibited camping, sitting on the sidewalk, and aggressive panhandling. By the later decades of the 20th century, the homeless population expanded to include women, families, and mentally ill persons who had been deinstitutionalized in the movement to return care to the local level. They were ever more visible and ever more subject to the ire of the community. Some city residents were aghast, insisting that a city's public spaces should be reserved for their intended uses—not for sleeping, bathing, and toileting. Advocates challenged the criminalization of homelessness, through statutes against vagrancy and public drunkenness, and the Supreme Court struck down vagrancy laws as a violation of the 14th Amendment in 1970. Yet cities continued to address inappropriate street behavior, bolstered by the "broken windows" theory as an explanation for the acceptance of lawlessness.

Efforts to address individual behavior while ignoring social and economic context included local ordinances that prohibited camping, sitting on the sidewalk, and aggressive panhandling. By the later decades of the 20th century, the homeless population expanded to include women, families, and mentally ill persons who had been deinstitutionalized in the movement to return care to the local level. They were ever more visible and ever more subject to the ire of the community. Some city residents were aghast, insisting that a city's public spaces should be reserved for their intended uses—not for sleeping, bathing, and toileting. Advocates challenged the criminalization of homelessness, through statutes against vagrancy and public drunkenness, and the Supreme Court struck down vagrancy laws as a violation of the 14th Amendment in 1970. Yet cities continued to address inappropriate street behavior, bolstered by the "broken windows" theory as an explanation for the acceptance of lawlessness.

Responding to the problems of the unsheltered by increasing police enforcement of street behavior ignores the increasing diversity of homeless populations. As of 2015, 37% of homeless people were families with children, 64% experienced homelessness as individuals, and 6% were children.

Howard concludes on a hopeful note by citing the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development’s (HUD) Interagency Council on Homelessness’s (USICH) 2010 plan, “Opening Doors: Federal Strategic Plan to End Homelessness,” which builds on existing programs with the goal of ending homelessness of veterans in five years, of families in ten years, and all homelessness, eventually. The plan moves away from blaming the poor, accepting the reality of lack of affordable housing and the need for income supports and access to health care.

Homeless: Poverty and Place in Urban America was published in 2013. As an update, note that President Trump’s 2018 budget proposed eliminating funding for USICH [pdf] and allowing the agency to sunset when its authorization expires on October 1, 2018. However, the tax plan approved by the House of Representatives maintains current levels of spending for homeless assistance. The Senate's version of the tax plan slightly increases spending, which allows for programs to maintain capacity, but falls further behind the actual need.

Howard's work is important for understanding this heartbreaking social problem because it links the people who experience homelessness to the places they inhabit in American cities. Policy makers are faced with the cost of responding to the disparate needs of the unsheltered in a context of some city residents' consternation over the visible evidence of extreme poverty spreading beyond downtown into the neighborhoods. For examples from my home city of San Francisco, here are images of encampments, one under a freeway and the other on a residential street.

(Images courtesy of Christopher Kent O’Leary)

Now the city’s public spaces, its sidewalks, parks, and libraries, are the province of the unsheltered, while privatized public spaces, where standards of decorum can be enforced, are enjoyed by persons who do not appear bedraggled. At the Ferry Building, a restored 1898 Beaux Arts style building on the bay that continues to serve as a ferry terminal, its ground floor transformed into a food hall celebrating the bounty of Northern California, people wait in line to enjoy a $50 oyster bar lunch. While just outside, in Justin Herman Plaza and Sue Bierman Park, the indigent are encamped with shopping carts that carry their toilet paper and other worldly possessions.

Maui's Vacation Rental Debate Turns Ugly

Verbal attacks, misinformation campaigns and fistfights plague a high-stakes debate to convert thousands of vacation rentals into long-term housing.

Planetizen Federal Action Tracker

A weekly monitor of how Trump’s orders and actions are impacting planners and planning in America.

In Urban Planning, AI Prompting Could be the New Design Thinking

Creativity has long been key to great urban design. What if we see AI as our new creative partner?

King County Supportive Housing Program Offers Hope for Unhoused Residents

The county is taking a ‘Housing First’ approach that prioritizes getting people into housing, then offering wraparound supportive services.

Researchers Use AI to Get Clearer Picture of US Housing

Analysts are using artificial intelligence to supercharge their research by allowing them to comb through data faster. Though these AI tools can be error prone, they save time and housing researchers are optimistic about the future.

Making Shared Micromobility More Inclusive

Cities and shared mobility system operators can do more to include people with disabilities in planning and operations, per a new report.

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.

planning NEXT

Appalachian Highlands Housing Partners

Mpact (founded as Rail~Volution)

City of Camden Redevelopment Agency

City of Astoria

City of Portland

City of Laramie