What will it take to keep families in cities?

A few months back, Toronto's Deputy Mayor started a political flap, stating on the floor of City Council that downtown was no place to raise kids! "Where's little Ginny? Well, she's downstairs playing in the traffic on her way to the park," he exclaimed.

Flap, indeed. Urbanists and parents alike were quick to denounce the comment, including me. In a way though, we might thank the Deputy Mayor for saying candidly what unfortunately many politicians, and many parents, might still think.

I heard similar comments from a Calgary council member years ago while I was leading that city's Centre City Plan. We're dreaming if we think families will move downtown, the Alderman told me.

I heard it with great conviction from a San Francisco urbanist who shared a panel with me at a Rotterdam Smart Cities conference. Downtowns will never attract families, he proclaimed to the crowd.

Most recently, I heard it on a tour of Seattle's downtown, perhaps to rationalize that city's disappointment so far in attracting families, even as they build many new downtown homes. Do downtowns really need families to be successful neighbourhoods? What's wrong with singles and seniors, and lots of ‘em?

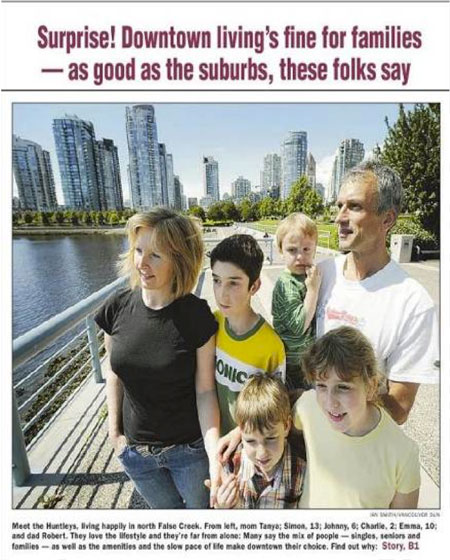

Having considered this issue in dozens of downtowns I've worked in, most recently as part of my six years as Chief Planner here in Vancouver (considered a significant North American success in attracting families downtown), I keep coming back to an old saying amongst urbanists: "kids are the indicator species of a great neighbourhood."

To elaborate, if there are no kids downtown, or in any inner-city neighbourhood, there's probably a good reason. There's likely something wrong or missing in the community, since families are a natural human condition. And as I'll explain in this post, it matters that something is missing. Further, you CAN fix what's missing, if you really want to. Unfortunately, many cities aren't doing what's necessary to make downtowns attractive to families.

The truth is that many downtowns are currently not great places to raise families, because they are not designed to be. It's a self-fulfilling prophecy. A city gives up on kids downtown, as does the home-building industry, so no one designs and plans for them. No schools. Little daycare. No playgrounds, facilities or a basic public environment to make downtown kid or teenager-friendly. Most importantly, no homes built that could actually fit a family. Perhaps a couple, but as soon as baby comes, they start planning the move. This perpetuates the theory that families would never want to live downtown.

My good friend Peter Rees, the Chief Planner for London, England, once proclaimed to a New York audience we were jointly presenting to, that "kids kill downtowns", referring to the NIMBY that can result when families complain about the noise from night-life and such. He has a point – I saw this in spades, when families in our very mixed Yaletown community argued successfully against a proposed rooftop patio on the Opus Hotel. Although his point is valid, his sphere of interest is that square mile of very central London, equivalent to our focused central business district. When we think of the downtown, we think much more broadly than the CDB. Peter agrees with this important distinction, and acknowledges the success we've had in our broader Vancouver downtown, mixing families, strategically located night-life, and urban energy by artful community and even building design. And yes, we have families in our CBD too – but not as many, as we emphasize job-space there, and are very strategic about housing of any type. Is it perfect? Far from it, and there are indeed tensions, but what it is, is urban, vital, and diverse – what downtowns should be.

So should we want families downtown?

I strongly believe we should. They're a big part of complete, mixed, vibrant and lively downtown neighbourhoods. Singles, seniors and couples downtown may be great, but kids and baby-strollers make communities more real, more human. They also support a broader local economy, and make the community safer.

Cities across North America and the world are having that tough discussion about what it really takes to attract families downtown. Oslo, Norway mandated in 2007 that half of all new homes be sized for 3 bedrooms and families. Minneapolis's Mayor has been asking the tough questions around attracting downtown families. Edmonton Alberta's Mayor recently hoped that their development of former inner city airport lands could specifically attract families. And yes, there's the debate in Toronto.

Further, the debate isn't confined to ‘traditional" downtowns. Families are clearly a big issue in inner-city and streetcar suburbs, but also in new suburban downtowns and transit town centres as we seek to urbanize the suburbs. This is a very good thing, as diversity including families will be a key success indicator for these new suburban downtowns as they develop.

The good news is that when downtowns are deliberately and proactively designed for kids, the families come. The proof is here in Vancouver. Within our general success story of growing our Downtown population from 45,000 decades ago, to over 100,000 people today, our growth in children is unique; about 7000 kids in our Downtown peninsula. That's a huge growth, inspired by vision, and achieved by design.

So how do you design a downtown for families? As a general philosophy, it starts with planning and designing with the parent and child in mind. Is this a place kids want to be? A place where parents have what they need, family-raising infrastructure and support systems? We like to say "a neighbourhood that's designed to work for kids, works for everyone."

Even if you get the design details right, families have a hard time making life work downtown without two key elements; child-care, and nearby schools. In Vancouver, we've been using density negotiations to have new developments pay for the construction, and sometimes part of the operating, for hundreds of new day-care spaces downtown, designed into new buildings (often on the roofs of podiums). This is a key amenity for families, as much or more than a park or a community centre can be. Although there has been real success in building new child-care spaces, the costs and waiting lists are still daunting.

As for downtown schools, this is one of the toughest parts, especially in American cities. In Canada, the public school system doesn't geographically skew funding of schools to the suburbs, so the key is usually to show the school boards that kids are there, or will be. A sort of "if they come (kids), they will build it (schools)." In Vancouver, we prioritized schools by negotiating 2 school sites from larger developments many years ago. The first elementary school, Elsie Roy, opened many years ago to full classrooms. The second site, in International Village, has finally had its construction funding announced by the Province of British Columbia. The wait has been long, even though the students have been there for many years, having to "commute" out of the downtown while waiting for construction. Many parents gave up after waiting years, illustrating the need to change Provincial school construction funding models to be more proactive and strategic.

If elementary schools are a challenge, perhaps high schools are even tougher. This is where Vancouver's achievement is less impressive. Once kids reach their teenage years, having to "commute" out of the downtown to a high school can make parents think twice about staying. This is especially true if bigger kids are making the home seem tighter, and if the community lacks hang-outs for teens. This is where community centres, skateboard parks, and other teen-focused amenities are critical.

Perhaps the most important family infrastructure a downtown can have, not surprisingly, is housing that actually fits families. It's amazing how many downtowns aspire to have families, and still don't ensure that family-friendly housing is built.

This was the exact debate in Toronto that sparked the Deputy Mayor's comments, a debate over requiring 10% of homes in projects be 3+ bedrooms. Toronto's Councilor Adam Vaughan (who made the motion) and his staff have met with us in Vancouver many times, and know well that for many years we've mandated 25% of units be 2+ bedrooms. Vancouver has debated internally if that's enough, or if we should have 10% of units be 3 bedrooms as well. I remain a supporter of such a change, as 2 bedrooms just aren't enough for many families.

Many will say that bigger downtown homes sized for families will be too expensive for families to afford. Although this is a key issue, I'm always quick to point out that larger units with more bedrooms usually sell for less per square foot than singles and studios (one of the reasons developers may not chose to build them, if they aren't required to), and are often on the ground floor (ie podium rowhouses) or lower in the building, with corresponding lower prices per square foot. Vancouver has shown that families CAN afford units downtown, even if not EVERY family can. When combined with Vancouver's rental and social housing requirements (20% of unit potential must be set aside for social housing, and rental housing is given density bonuses and other incentives), families of different economic circumstances can be part of the result. It's not easy, and affordability for families is a significant challenge, but it's simply not true that affordability will prevent families from moving downtown.

Even if all the vision, supporting design and family-friendly infrastructure is there, will parents choose downtowns over the suburbs? Vancouver has shown that not all parents will, especially if family-friendly housing downtown is too expensive for many. However many parents do, and enthusiastically so, because a well designed downtown is a great place to raise a family.

What's certain is that if cities have this vision, we need to stop designing downtowns to be un-welcoming to families, and start inviting parents to enthusiastically choose downtown living. Our downtowns, and our kids, will be better for it.

(A much shorter version of this article first appeared in Huffington Post BC)

Maui's Vacation Rental Debate Turns Ugly

Verbal attacks, misinformation campaigns and fistfights plague a high-stakes debate to convert thousands of vacation rentals into long-term housing.

Planetizen Federal Action Tracker

A weekly monitor of how Trump’s orders and actions are impacting planners and planning in America.

Chicago’s Ghost Rails

Just beneath the surface of the modern city lie the remnants of its expansive early 20th-century streetcar system.

Bend, Oregon Zoning Reforms Prioritize Small-Scale Housing

The city altered its zoning code to allow multi-family housing and eliminated parking mandates citywide.

Amtrak Cutting Jobs, Funding to High-Speed Rail

The agency plans to cut 10 percent of its workforce and has confirmed it will not fund new high-speed rail projects.

LA Denies Basic Services to Unhoused Residents

The city has repeatedly failed to respond to requests for trash pickup at encampment sites, and eliminated a program that provided mobile showers and toilets.

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.

planning NEXT

Appalachian Highlands Housing Partners

Mpact (founded as Rail~Volution)

City of Camden Redevelopment Agency

City of Astoria

City of Portland

City of Laramie