One common argument against statewide zoning reform is that local control of zoning is a venerable democratic norm. But in fact, state government often controls local land use in a variety of ways.

In recent years, some state governments have sought to reform local zoning by limiting localities' ability to exclude new housing. One of the most common arguments against such reform is that local control of zoning is so well-established as to be a democratic norm. For example, Aaron Renn writes that banning single-family zoning involves a “shift from local to state control... [that] would completely upend this country's traditional approach to land use.” (1)

But in fact, state government already interferes with local control in a variety of ways, especially in regulation-addicted states like New York. For example:

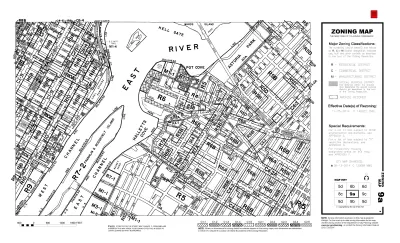

*The state caps floor-area ratio at 12. This means that a landowner cannot build anything with over twelve stories, unless it a) allows some floor area to go unused or b) purchases development rights from other landowners or otherwise takes advantage of arcane zoning loopholes. This law seems to be limited to New York City. Because car pollution is reduced when people are allowed to build housing and offices in places which (like New York City) have lots of public transit, this law seems to be environmentally harmful. (2)

*The state has an environmental review statute which ensures that large-scale construction can be delayed by environmental impact statements. Since state courts have the right to require supplemental environmental impact statements, this means that development opponents can (in theory) delay building by claiming that every environmental statement failed to consider something. Although this law is not limited to New York City, as a practical matter it targets infill development. Why? Because development at the edge of suburbia may not have as many neighbors as infill development, which means there are fewer people who are tempted to use state law to slow down such development.

*Rent control is governed by state law.

In addition, issues related to automobile traffic are often governed by state law. For example, the city had to get state permission to implement congestion pricing in Manhattan, and to slow down traffic with speed cameras.

Admittedly, some of the abovementioned laws are roughly similar to what some local governments would do without state interference: for example, New York City has its own floor-area requirements. But state law deprives cities of the flexibility that they can use to tweak or reform those laws.

So in New York, local control seems to be a widely accepted norm only as to regulations that limit housing supply or facilitate dangerously fast automobile traffic. But if a city's government wants to allow more housing or to protect its citizens from car pollution and traffic violence, the state is quite happy to intervene.

If New York's experience is typical, local control is our “traditional approach to land use” only when it creates suburban sprawl or makes streets more dangerous.

(1) Incidentally, this statement is questionable for a reason unrelated to this article: Renn admits that most of these reforms involve allowing landowners to substitute four-plexes for single-family homes. But since this still allows exclusion of larger apartment buildings, this seems to be to be a very modest reform—I suspect too modest to do much good.

(2) One common counterargument is that high-rises are less energy-efficient than shorter buildings. I have responded to that argument in Sec. IV_D of this article.

Maui's Vacation Rental Debate Turns Ugly

Verbal attacks, misinformation campaigns and fistfights plague a high-stakes debate to convert thousands of vacation rentals into long-term housing.

Planetizen Federal Action Tracker

A weekly monitor of how Trump’s orders and actions are impacting planners and planning in America.

San Francisco Suspends Traffic Calming Amidst Record Deaths

Citing “a challenging fiscal landscape,” the city will cease the program on the heels of 42 traffic deaths, including 24 pedestrians.

Bend, Oregon Zoning Reforms Prioritize Small-Scale Housing

The city altered its zoning code to allow multi-family housing and eliminated parking mandates citywide.

Amtrak Cutting Jobs, Funding to High-Speed Rail

The agency plans to cut 10 percent of its workforce and has confirmed it will not fund new high-speed rail projects.

LA Denies Basic Services to Unhoused Residents

The city has repeatedly failed to respond to requests for trash pickup at encampment sites, and eliminated a program that provided mobile showers and toilets.

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.

planning NEXT

Appalachian Highlands Housing Partners

Mpact (founded as Rail~Volution)

City of Camden Redevelopment Agency

City of Astoria

City of Portland

City of Laramie