The Portland Clean Energy Community Benefits Fund stands out as an example of local grassroots climate action—in this case, the kind of action that makes other climate projects and programs possible.

Leading U.S. cities are updating their climate action plans to emphasize racial equity and social justice, but their efforts are constrained by a scarcity of funding for implementation. One instructive exception is Portland, Oregon, where activists succeeded in creating a new source of ongoing revenue for climate justice initiatives—a surcharge on the gross receipts of large retailers.

The surcharge, which will generate between $80 and $90 million annually, came to be because of a ballot measure overwhelmingly passed by Portland residents in November 2018. The measure called for imposing a surcharge to create a dedicated funding stream to support climate initiatives that advance racial and social justice.

The law created by the ballot measure charges large retailers (with gross revenues of more than $1 billion nationally and $500,000 locally) a one-percent surcharge on gross revenues from retail sales in Portland (exempting groceries, medicines, utilities, and health care services). The millions of dollars the surcharge will generate is enough for more than a token commitment to climate justice.

Many outside people think of Portland as one of the nation’s most liberal and environmentally conscious cities. It’s a well-earned reputation: Portland was the first with a climate action plan (1993), one of the first to focus its climate action on equity (2015), and one of the first to impose a fossil-fuel ban that prohibits expansion of existing terminals and limits new ones (2016). But it took several years of grassroots organizing to get the political support needed for the ballot initiative. The Portland City Council wasn’t ready to embrace the idea when it emerged, and then-Mayor Charlie Hales spoke out against it publicly.

The idea was several years in the making. Environmental activists Lenny Dee and Adriana Voss-Andreae from 350PDX, a grassroots movement focusing on justice-based solutions to climate change and building a regenerative economy, Jo Ann Hardesty, president of the Portland NAACP chapter (now also a Portland City Commissioner), and environmental lawyer Brent Foster came up with the broad outline of the campaign and a commitment that it would be led by Black, Indigenous, Latino, and Asian-American organizations. This was a major transition for 350PDX, Voss-Andreae told me, and it took almost two years to organize the coalition.

Further, none of the groups had worked on a ballot initiative or directly confronted corporations before. As several organizers told me, such a campaign was “outside their organizing comfort zone.”

The coalition finalized the ballot initiative language in 2017 and soon after began hiring campaign staff to conduct outreach and media events, focusing particular attention on racially and ethnically diverse neighborhoods with typically low election turnout. By joining efforts with organizers of another ballot initiative, No on 105, which protected an existing sanctuary law and placed limits on police cooperation with federal immigration agents, the campaign was able to contact 60,000 people and deliver about 500,000 mailers. Eventually they collected more than 200 endorsements, including community and environmental organizations, labor unions, and businesses.

It helped that the opposition was not as strong as the organizers expected. Rather than building a business coalition in opposition, the big-box companies tried to enlist minorities as fronts for the opposition, which backfired. The Portland Business Alliance led a campaign, Keep Portland Affordable, which made an unconvincing case that the tax would cost Portland families $200 a year.

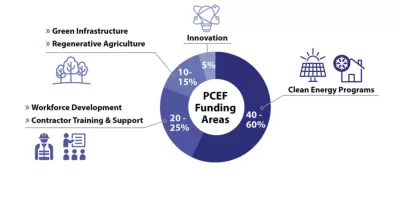

The Portland Clean Energy Community Benefits Fund (PCEF) is now a reality, prioritizing funding in four broad areas: 40-60 percent on renewable energy and energy efficiency programs; 20-25 percent on clean energy job training, apprenticeships, and contractor support; 10-15 percent on regenerative agriculture and green infrastructure programs; and 5 percent on future innovation. The four principles that guide the PCEF in choosing projects are that they must be justice driven, accountable, community powered, and focused on action with multiple benefits. In making awards, projects are required to use domestically produced renewable energy products; sign a Workforce Contractor Equity Agreement; and meet family wage standards.

For PCEF to allocate that much money and for organizations to spend it wisely takes considerable capacity building. In April 2021, PCEF distributed $8.6 million to 38 organizations for projects such as Depave, the African American Home Ownership Alliance, and Verde Builds.

The PCEF is administered by a nine-member grant committee appointed by the mayor and confirmed by the city council. The committee reflects the ethnic diversity of the city, with members who have demonstrated experience in the type of projects supported by the fund. Project staff are housed at the city’s Bureau of Planning and Sustainability. The grant committee makes funding recommendations to the mayor and city council.

To ensure that funds are spent wisely, the PCEF limits administrative spending to 5 percent of revenues, with exceptions in early stages of program development. Staff describe the status of the PCEF as program development and community capacity building—working with organizations on scaling up to handle this amount of money. As one community organizer told me, “if we don’t get it right, the press will be all over it.”

What can other cities learn from the nation’s first climate fund organized and managed by communities of color? Organizing an inclusive and effective campaign is everything and

Voss-Andreae, has published a detailed report, “Template for Building a City Green New Deal,” that organizers can use to replicate Portland’s approach.

However, Republican state legislatures are preempting local green initiatives in many states. Already, the Oregon Legislature, at the time majority Democrat, passed legislation that prohibits other Oregon cities and towns from introducing ballot initiatives to create similar funds. The preemption provision was added to an education bill years in the making, the Student Success Act, which would inject $1 billion of additional funding into the k-12 system. Business groups agreed to support higher taxes to fund the bill only if it contained a preemption provision so other cities and towns wouldn’t be able to replicate Portland’s surcharge. Many of the groups behind PCEF supported the much-needed education bill and did not voice opposition to the provision.

Still, green justice funds are moving in other cities unconstrained by state preemption. In November 2020, Denver voters passed Ballot Measure 2A, which increased the sales tax by .25 percent (from 8.31 to 8.56 percent) to generate about $40 million annually for programs to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and air pollution. Like PCEF, the funding will prioritize workforce training for low-income residents and target investments in communities of color and low-income neighborhoods.

Yet, even in a climate-leader city like Berkeley, Ballot Measure HH lost. It would have increased taxes on electricity and gas from 7.5 to 10 percent to create a Climate Equity Action Fund. This may have been tactically unwise, because the proposed tax hit citizens rather than a small number of corporations. It's not clear whether the loss in Berkeley signals that few cities will be able to replicate the successes of Portland and Denver. But, as I’ll reveal in my next posts, there are other options at the state level that will benefit cities committed to climate justice.

Maui's Vacation Rental Debate Turns Ugly

Verbal attacks, misinformation campaigns and fistfights plague a high-stakes debate to convert thousands of vacation rentals into long-term housing.

Planetizen Federal Action Tracker

A weekly monitor of how Trump’s orders and actions are impacting planners and planning in America.

Chicago’s Ghost Rails

Just beneath the surface of the modern city lie the remnants of its expansive early 20th-century streetcar system.

Bend, Oregon Zoning Reforms Prioritize Small-Scale Housing

The city altered its zoning code to allow multi-family housing and eliminated parking mandates citywide.

Amtrak Cutting Jobs, Funding to High-Speed Rail

The agency plans to cut 10 percent of its workforce and has confirmed it will not fund new high-speed rail projects.

LA Denies Basic Services to Unhoused Residents

The city has repeatedly failed to respond to requests for trash pickup at encampment sites, and eliminated a program that provided mobile showers and toilets.

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.

planning NEXT

Appalachian Highlands Housing Partners

Mpact (founded as Rail~Volution)

City of Camden Redevelopment Agency

City of Astoria

City of Portland

City of Laramie