Ken Greenberg explores the need to develop new urban manners as the increasing interest in city-living drives North Americans to live in close quarters in denser urban neighbourhoods. The author of Walking Home: The Life and Lessons of a City Builder, which was recognized as one of Planetizen's Top Books of last year, Greenberg takes his argument further, by suggesting the behaviors by which competing interests can be balanced in our increasingly urban environments.

North Americans are moving into downtowns and older neighborhoods along transit corridors in unprecedented numbers. There, in the quest for shorter commutes and convenience, they are rediscovering a new competing urban version of the North American dream. It looks different – not the mansion on the hill set back in the landscape with a sweeping drive and fleet of cars, nor its scaled down cousin in an upscale subdivision, but living in a more modest dwelling in a neighborhood where you can walk to buy groceries and take transit to work. Beyond the real estate hype, this change in lifestyle brings a significant change in outlook as people make adjustments, weighing personal priorities like getting rid of the second car and even the first, getting on a bicycle or walking to work, living in a smaller space, trading a yard for a balcony or roof top garden, using smaller appliances and generally living with less stuff.

North Americans are moving into downtowns and older neighborhoods along transit corridors in unprecedented numbers. There, in the quest for shorter commutes and convenience, they are rediscovering a new competing urban version of the North American dream. It looks different – not the mansion on the hill set back in the landscape with a sweeping drive and fleet of cars, nor its scaled down cousin in an upscale subdivision, but living in a more modest dwelling in a neighborhood where you can walk to buy groceries and take transit to work. Beyond the real estate hype, this change in lifestyle brings a significant change in outlook as people make adjustments, weighing personal priorities like getting rid of the second car and even the first, getting on a bicycle or walking to work, living in a smaller space, trading a yard for a balcony or roof top garden, using smaller appliances and generally living with less stuff.

We are picking up a thread where we left off three generations ago when denser North American cities had apartment buildings, streetcars and active shops on main streets, dusting off and reviving an urban culture that had all but disappeared with the rare exceptions of parts of cities like New York, Boston, San Francisco, Montreal that maintained the kind of vertical and compact neighborhoods commonly found in other parts of the world. We are flexing urban muscles that we didn't know we had, rediscovering the joys of the flâneur, the wanderer with no fixed destination, trying out new places, experiencing the amazing diversity, rubbing elbows with people of different ages and moments in their lives.

Still, as with all major shifts, there are also big challenges. The most significant is maintaining and expanding the range of housing options in these newly forming neighborhoods for people of different income levels and different needs in a time of austerity but also a sometimes callous lack of commitment to social equity. It may feel like urban living is now reserved for the rich, but when the subsidies to the alternative are stripped away and the true costs revealed it is actually inherently more affordable. We need to level the playing field and make this work with inclusive zoning and price supports to address the needs of all ages and conditions including the growing population of seniors and young families who are seeking better alternatives.

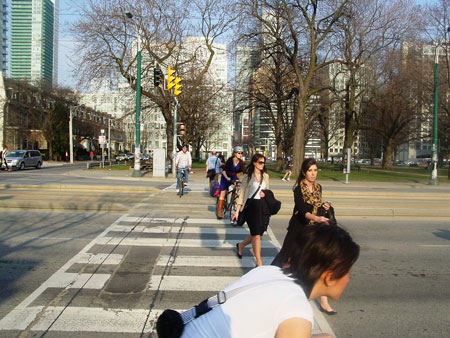

There are other growing pains related to how we share space in the city. We grew used to spreading out in the auto-oriented suburbs established in the decades following World War II, avoiding friction with our neighbors by using space as a buffer, driving from place to place for specific purposes but rarely overlapping on foot in public spaces. Backyards on leafy neighborhood streets were the outdoor living rooms for kids to play, dogs to run and the focus of family life. As this change to greater density gathers momentum a combination of urban newcomers – often young people living on their own for the first time and from an increasingly polyglot mix of cultures with as many assumptions as to what constitutes acceptable behavior, find themselves thrown together in close quarters. With the switch to denser apartment-style living chance encounters multiply and that means becoming more conscious about how we interact, sharing public space and negotiating a whole new set of relationships as part of city life. Here are a few of the frustrating situations coming to light as we bump into each other in some cases quite literally.

In the many downtown city streets that were largely devoid of pedestrians for most hours of the day, cars once had their own way. Now with vast increases in residents, a growing number of walkers and cyclists are competing with drivers for limited space. This is leading to evident frustration and bad behavior, but more than that, the conflicts can be life threatening. Last year a pedestrian was hit by a car in Toronto every 3 ½ hours while a cyclist every 7 hours and 10 minutes, and these are just the cases reported to the Toronto Police. It is all very well to say people should just follow the rules, but what rules? All may be at fault – impatient drivers who think the roads are theirs alone gun their engines to beat the light ignoring pedestrians and cyclists; multi-tasking pedestrians who text obliviously while crossing the street; and kamikaze cyclists who weave through traffic and on sidewalks recklessly in their own bubbles. Compounding the problem, mid-twentieth century streets, inadequately designed for the volume and variety of new users, send ambiguous signals. How should a cyclist make a left turn at an intersection on a busy street? Go with the traffic and get in the left lane or join the crosswalk conflicting with pedestrians. It isn't obvious. Should cyclists stay off the sidewalks even where the lanes are too narrow and fast moving traffic is treacherous? Improvising is dangerous and anxiety-producing when there is no shared understanding about how to navigate the streets and sidewalks.

This is clearly a case where we need to both change our behavior and redesign the limited space available in the rights-of-way for the greater good, rather than seeing it as a zero sum game among competing users. The great examples, cities like Amsterdam and Copenhagen, have developed highly sophisticated designs for shared use that do just that, with separated lanes for cyclists in many locations, pedestrian priority crossings and signals adapted to all users. Seeing these solutions in action, it's obvious that when there's clarity, all users tend to be calmer and more considerate. Peer pressure and ‘follow the leader' behavior kicks in – at intersections, waiting at lights, etc. The flow works and there's less sense of the stress and danger which comes from uncertainty.

We can also learn from cities in the developing world. In India, for instance, the seemingly impossible nonstop rhythm of streets works only because of constant eye contact among pedestrians and the drivers of an unbelievable variety of conveyances-cars, trucks, buses, rickshaws (motorized and pedaled), bicycles, motorcycles and mopeds. This phenomenon relies on low tech human interaction as a complement to the minimum of essential signage and signals, and has been taken up in the latest sophisticated European engineered streets in what are sometimes called "naked streets." By deliberately reducing the number of traffic signs in the right circumstances, this approach encourages eye contact and increases pedestrian safety.

The need for actually seeing each other and overcoming our hurried self-absorption also holds true for sharing space in transit vehicles – increasingly crowded subways, streetcars, and buses. We need to become much considerate of the growing numbers of the less able, seniors for example, who are downtown dwellers or parents with children or pregnant women. Small gestures like giving up a seat, offering a helping hand or giving directions go a long way.

Another front where we are seeing intense competition for space in the emerging downtown neighborhoods is the tension that sometimes arises between dog owners and others including young parents with kids vying for space in city parks and squares. There has been an incredible proliferation of dog ownership especially among young people, and often more than one per household. In my neighborhood it is estimated that over 50% of the new units produce a dog. So dog walking and dog playing (often with ball throwing devices for greater distance), have begun to place an extraordinary demand on parks and have created a whole new form of socializing, which occurs several times a day. But this demand is increasing at the same time that other park uses are also growing, and young families want to be in the same parks with their kids who are often fearful around large dogs running freely. This is leading to unfortunate animosity as each side jealously guards its prerogatives and protects turf. A fair negotiation of the rules and a protocol for sharing of spaces is clearly needed. In many places, clearly defined on-leash and off-leash areas have been successfully established, but sometimes there is just not enough room for all who want to use park space. Innovative solutions for using found spaces such as rooftops and laneways, and carving out added park space are needed. But most important is the willingness to compromise, acknowledging the needs of the other.

We readily say we love mixed-use but it too can sometimes be a challenge. Restaurants and cafes can make great and convenient neighbors, but an overconcentration of a noisy, intrusive uses like nightclubs in residential areas steps on others' toes. Controlling the level of the music on patios and termination times, avoiding closing time rowdiness and antisocial behavior like throwing beer bottles and cigarette buts -- in short respecting the presence of others -- become the necessary pre-conditions that make this sharing of the neighborhood space possible and agreeable.

Living in a big city doesn't take away the human need to trust that our fellow citizens will show some level of respect, to feel welcome and safe, to take pride in and ownership of our surroundings. We do this wonderfully in times of great adversity, and come to each other's aid in crises, but what about the rest of the time? Every city has its unspoken codes, along with its more formal written laws and regulations, that shape the course of daily life and frame the ways people experience each other as fellow citizens and members of society. We use the term civility, from the Latin civilis (meaning "proper to a citizen") to describe how we believe people should behave in relation to others. As we change our living patterns to live at higher densities, we also need to become more mindful of others and our impacts. This is true even in dense cities with the relative anonymity that can be a welcome relief from the kind of small town community where everyone knows everyone's business.

All things being equal, the real measures of successful urbanity may be in the demonstrations of mutual respect while living at close quarters, the degree to which we are comfortable with each other, the room we make for children and seniors, the tolerance and even embrace of our differences, and the accumulation of small acts of kindness. This doesn't mean standoffishness or keeping one's distance. Our interactions can be gruff, teasing and humorous, or inquisitive and friendly; they can involve some measure of risk but still speak to some sense of fellow feeling and connection to our shared sense of place.

We are still in the early stages of this profound shift in how we will live in North America, and the conflicts described above are really enviable problems of urban success experienced as growing pains. People in cities do have the capacity to adjust. For proof that such adaptation is possible, we have only to look at things like the changing attitudes to smoking in public, the success of "poop and scoop", and the move to universal access. The ways in which this all gets worked out will of course be particular to each city, drawing on its local culture and traditions as it figures out ways to make life together bearable and even pleasurable. It may seem antiquated in a world of ubiquitous hand held devices and the temptation to tune out face-to-face contact, but critically important in all this is the need to see each other and make eye contact as we acknowledge each other's presence and needs.

Ken Greenberg is an architect, urban designer, teacher, writer, former Director of Urban Design and Architecture for the City of Toronto and Principal of Greenberg Consultants. He is the recipient of the 2010 American Institute of Architects Thomas Jefferson Award for public design excellence and the author of Walking Home: the Life and Lessons of a City Builder, published by Random House, which was recognized as one of Planetizen's Top Books of last year.

Maui's Vacation Rental Debate Turns Ugly

Verbal attacks, misinformation campaigns and fistfights plague a high-stakes debate to convert thousands of vacation rentals into long-term housing.

Planetizen Federal Action Tracker

A weekly monitor of how Trump’s orders and actions are impacting planners and planning in America.

In Urban Planning, AI Prompting Could be the New Design Thinking

Creativity has long been key to great urban design. What if we see AI as our new creative partner?

King County Supportive Housing Program Offers Hope for Unhoused Residents

The county is taking a ‘Housing First’ approach that prioritizes getting people into housing, then offering wraparound supportive services.

Researchers Use AI to Get Clearer Picture of US Housing

Analysts are using artificial intelligence to supercharge their research by allowing them to comb through data faster. Though these AI tools can be error prone, they save time and housing researchers are optimistic about the future.

Making Shared Micromobility More Inclusive

Cities and shared mobility system operators can do more to include people with disabilities in planning and operations, per a new report.

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.

planning NEXT

Appalachian Highlands Housing Partners

Mpact (founded as Rail~Volution)

City of Camden Redevelopment Agency

City of Astoria

City of Portland

City of Laramie