The rules of placemaking haven't changed since ancient times - people seek comfort, variety, entertainment and walkability. As designers resurrect ideas discarded over the last few decades, landscape architect Trent Noll offers some best practices for placemaking using modern techniques.

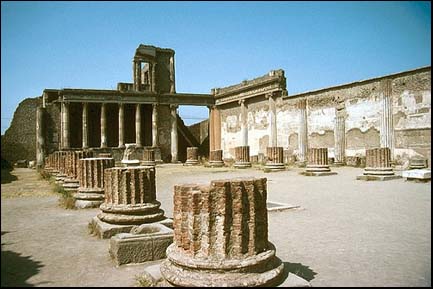

The business and practice of making a successful urban place may be nearly as old as cities themselves. Indeed, the discerning archeologist studying the habits of the early market street in excavated Kirkuk or Pompeii sees vestiges of the same elements developers today consciously employ in placemaking.

What attracted wayfarers to the main boulevards of ancient cities were entertainment, comfort, variety, walkability, sustenance, convenience, people-watching, safety and security, commons areas, and natural elements, such as trees, gardens, and water features. A successful place was enhanced by evocative or triumphal entrances, signage, iconic wayfinders, memorable architecture, and beautiful landscapes.

Today, the placemaker must meet timing expectations and budgets, be mindful of current regulations and building codes, and be especially aware of the immediate pressures of public development goals. Within the modern context, city planners or developers have a compressed delivery time to create what often took lifetimes of organic development (including much trial and error) in previous eras. The margin for missteps has been radically curtailed however, especially from the perspective of the private-sector developer.

Moreover, locomotion has changed from days of yore. As a practical matter of convenience, if a place is successful, there will be more visitors and hence increased demand for proximate parking. A transition to solve these challenges, which require convenient, yet not obtrusive or unsightly, parking structures, are commonplace in developments of today.

Modern Placemaking

Despite the financial pressures and perils of modern placemaking, domestically and globally we see cities and developers turning to architects, landscape architects, and urban planners to craft places that attract tenants and customers from early morn through late evening, thereby extending the urban life cycle of a place.

In many ways, the art of making a place where people want to gather and live today involves a restoration of nostalgic sensibilities that some Americans have lost, yet are still holding strong in small-town America-a central Main Street or square, fronted by town walks, civic buildings, specialty retailers, family eateries, downtown live-work housing, neighborhood theater, central park with town square, and massive street trees. In brief, the historic norm evolved functionally with gathering places to shop, mingle, live, work, eat, rest in the park, stroll, take in a movie, people-watch, and meet friends. Even before the emergence of "mixed-use" as a popular urban planning buzzword, Americans were naturally enjoying the benefits.

Domestic population growth, suburbanization, and the ubiquitous automobile in the Post-War era in many cities changed the traditional Main Street ideal. And for several decades, what replaced Main Street was not focused on a quality of experience, but on a drive toward the fastest, most convenient, and best value for the consumer. There is no gainsaying the convenience of the automobile, but many people-oriented Post-War business districts or shopping centers became inundated with cars, resulting in unsafe circulation conflicts. Too often what emerged in suburban America were strip- and big-box malls that were accessed primarily by cars conveniently parked in front of oversized buildings on large, treeless asphalt parking lots.

In some cases, new urban America gave way to single-use office campuses, the kind that emptied after the work was done. Office plazas became barren without healthy street-life, and were often unsafe for pedestrians. Most people arrived by car and punched out the same way. Nowadays developers and city planners understand that that inhospitality proved to be a bad business model. Public and private planners and developers are moving to partner together to refit failed projects of the past to bring new life to broken properties.

From misguided beginnings in the 1950s and 1960s, designers began to resurrect elements that had proved so successful in traditional placemaking. Landscape amenities in the resurrected town square, the street promenade, and central park gardens can change a place from vacant to inviting. Regional destination projects, including casinos and major-league athletic stadiums, have now evolved into mixed-used Meccas with resplendent landscapes, along with multiple dining and retail opportunities. And, of course, modern shopping developments are often full-fledged recreations of friendly, mixed-use urban zones.

It was not only nostalgia or "modern urbanism" that led to the placemaking renaissance, but a need to salvage revenues from failed commercial development models. If a casino, mixed-use office park, downtown shopping mall district, or resort isn't thriving 18 hours a day, it's bad planning and poor use of the developer's dollar and a city's taxable assets. It may seem expensive to provide landscape amenities, but for cities and developers it has become more expensive not to.

'Instant' Placemaking

Today's developers are redefining their properties with a "sense of place". From entrance to seating to shade, each component is a basic requisite that together creates authentic people places. What developers strive to create is a place that embodies a grand theme or captures a cohesive brand presence in order to drive maximum identification and appeal while enhancing the visitors' experience. Here are a few points about what goes into the art of placemaking:

Entrance, Portal, Welcome

At best, there is grandeur, even a hint of the momentous or mystical in the entrance. Ideally, passing through portals should not only literally but figuratively transport visitors into an alternative world, where business is more pleasant, and leisure finds delight in all five senses. Ideally, the successful place should be easily identified from approaches by such architectural features as grand gates, triumphal arches, distinctive signage, and monumental landscapes. The pavement should be textured and evocative, rather than simple asphalt. Colonnades of mature entranceway trees might enhance the approach, as would planted urns or hedges. Beautiful flowers can add to the ambiance.

Parking

Today, easy-to-read and thematic signage starts in the parking lot to connote "place" through color, font, or imagery. If possible, there should be views from the parking areas to monumental wayfinders at the store front. Negative views-of nearby freeways or adjacent industrial uses-should be softened or screened with walls, hedges, or trees. Shaded pedestrian promenades replete with linear canopy trees, pleasing pavements, landscaping, and lighting should guide visitors from vehicle parking to destination. Many projects can afford to build structured parking, which gets customers closer to their destination while shading the cars from the hot sun. These sometimes tall structures should be looked at for their architectural character and for signage opportunities. Structure edges can be softened by hedges, terraced gardens, and tall trees to transition them to the retail environment.

Orientation

Once people enter the entry promenades, walkways, and plaza gardens, they should be enveloped in a balance in scale of common gathering areas, preferably central commons areas, supported by proprietary outdoor patio dining spaces and inviting storefronts. Amenities, such as synchronized fountains, children's gym-sets, music, or koi ponds, should be deployed to entertain and provide interest. Hedges, trees, and potted plants help to further define edges while keeping sightlines open. A "ceiling" of mature trees provides filtered shade and varying light. Canopies and awnings identify retailers and add visual interest. Monumental wayfinders-such as tall obelisks or clock-towers-help patrons orient themselves and provide meeting points. Most successful places revolve around a commons area, be it a central park or linear street, that facilitates the flow of pedestrians within the development.

Pedestrian-Friendly Promenading

Though rarely mentioned, semi-private patio dining spaces and valet drop-off zones should have a view of common areas and promenades. Why? People-watching rarely wears thin-and to see and be seen is an ancient human diversion. The sense of shared public space and belonging to community mixed with semi-private sidewalk patio refuges is particularly effective. In brief, it is fun to be in the passing parade or to watch it-and people go to places that are fun. It goes without saying that promenading requires walkability, and people tend to feel more secure in places with lots of eyes and ears. The walking experience should be enhanced by appropriate signage, pavement, landscape definition and edging, and lighting. Colonnades and canopies of trees are especially delightful. Built-in seating on low-slung walls define the walkways while providing handy resting and waiting points.

Comfort

People need comfortable seating that is shaded, heated, or protected by wind screens. Depending on climate, there should be heaters or misters mounted to trellises or grand umbrellas. Shade and seating should be inviting and thematic, with ample lighting at night. In the drive for perceived authenticity, more planners and developers are specifying theme-appropriate shade trees for their courtyards, commons areas, atriums, and gardens. Architectural styles may come and go-what may seem lively one year is hopelessly garish the next-but nature is eternal and classic.

People need comfortable seating that is shaded, heated, or protected by wind screens. Depending on climate, there should be heaters or misters mounted to trellises or grand umbrellas. Shade and seating should be inviting and thematic, with ample lighting at night. In the drive for perceived authenticity, more planners and developers are specifying theme-appropriate shade trees for their courtyards, commons areas, atriums, and gardens. Architectural styles may come and go-what may seem lively one year is hopelessly garish the next-but nature is eternal and classic.

Sustenance, Food & Drink

Planners and developers are specifying that the landscape and architecture enhance a wide range of food and drink choices, some in or around the commons area, to encourage patrons to extend their stay. In response, many modern developments have vendors ranging from formal sit-down restaurants with patios to food kiosks. A food patio or court adjoining the commons area is often advantageous to activate all uses in the people space. The landscape firm enhances the activity with comfortable seating, fountains, foliage, attractive pottery, sculpture, art, and colorful landscape amenities.

Security

City planners and developers know that security is a prerequisite, and proper hardscape design and area lighting in the landscape design can contribute to that end. Darkened corners or back alleys are to be avoided for patron comfort and perceived safety. Open sightlines are important, and foliage or monuments should not result in 'hidden" areas. Whether a public or private space, the use of security cameras and information concierge booths and guard stations near entrances can be beneficial. A balance of building-mounted lighting, post-top mounted lighting on pathways and parking lots, and landscape lighting of trees all contribute to the sparkle and beauty-along with security-of a night-time space. Good lighting extends the retail usable hours of a center, encouraging users to stay longer.

Design-Build Placemaking

Plainly, the modern art of successful mixed-use placemaking-on time and on budget-is much more design-intense than the process of single-use office districts or tract housing developments.

For city planners and developers, the challenge is to create urban places with memorable characteristics that will entice retailers to invest in them. Too much uniformity in the fashion mix, little diversity in food and beverage choices, or not enough interesting interactive landscape amenities can spell defeat. For private developers, the goal is to make a long-lasting place that is flexible enough to grow and change over time, while making money doing it.

A worthy option is to turn to a design-build team from the start. Design-build helps control costs in such immensely detailed undertakings, in part because constructability is vetted from the get-go, and the relationships between designers and contractors throughout the design and construction processes are integral and unified.

In either public- or private-sector placemaking, landscape has become expected to reach success, due to the enduring human yearning and love for nature, and the developer's need to create projects that attract customers and tenants through the entire extended business clock.

In the design-build process, prime landscape opportunities are brought to the fore early on, before schedule constraints dictate either additional expenses or hard choices that could undercut the aesthetics and sense of place. Without expertly designed and built hardscapes and landscapes, the winning sense of place becomes almost unachievable. Most important, a unified design-build team can help ensure that overall project aesthetics and costs are consistent from the big idea to the smallest design detail where individual cost is married to project success.

The end result is a richer physical environ, and better return for all involved.

Trent Noll, ASLA, is senior principal and director of design for ValleyCrest Design Group, a global collective of award-winning landscape architects and designers specializing in world-class, sustainable, and forward-thinking landscape design. The company is lauded for its integrated design-build approach, completing projects from offices in Los Angeles and Orange County, Calif.; Orlando; Denver; and Shanghai, China.

Image credits:

2 Malibu Lumber Yard, Malibu, CA. photo: Williamson Images

3 Four Seasons Resort at Troon North, Scottsdale, AZ. photo: Williamson Images

Planetizen Federal Action Tracker

A weekly monitor of how Trump’s orders and actions are impacting planners and planning in America.

Chicago’s Ghost Rails

Just beneath the surface of the modern city lie the remnants of its expansive early 20th-century streetcar system.

San Antonio and Austin are Fusing Into one Massive Megaregion

The region spanning the two central Texas cities is growing fast, posing challenges for local infrastructure and water supplies.

Since Zion's Shuttles Went Electric “The Smog is Gone”

Visitors to Zion National Park can enjoy the canyon via the nation’s first fully electric park shuttle system.

Trump Distributing DOT Safety Funds at 1/10 Rate of Biden

Funds for Safe Streets and other transportation safety and equity programs are being held up by administrative reviews and conflicts with the Trump administration’s priorities.

German Cities Subsidize Taxis for Women Amid Wave of Violence

Free or low-cost taxi rides can help women navigate cities more safely, but critics say the programs don't address the root causes of violence against women.

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.

planning NEXT

Appalachian Highlands Housing Partners

Mpact (founded as Rail~Volution)

City of Camden Redevelopment Agency

City of Astoria

City of Portland

City of Laramie