This week, Hoboken is announcing its version of a highly successful awareness campaign practiced throughout Europe and, more directly translatable, the UK. In the UK, the campaign is called “20's Plenty for Us”, and in cities that adopt this policy, a 20mph speed limit area is established and signs are posted requiring drivers to obey the lower speed limit.

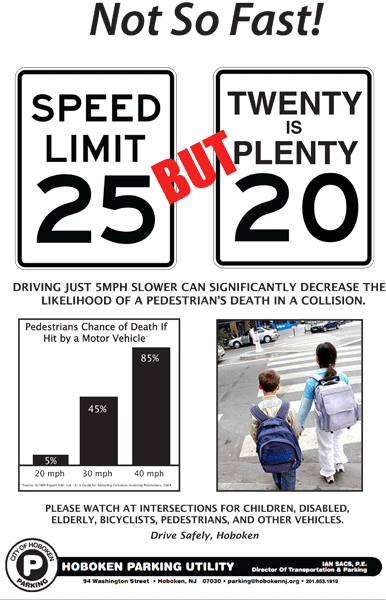

This week, Hoboken is announcing its version of a highly successful awareness campaign practiced throughout Europe and, more directly translatable, the UK. In the UK, the campaign is called "20's Plenty for Us", and in cities that adopt this policy, a 20mph speed limit area is established and signs are posted requiring drivers to obey the lower speed limit. While such a policy sends a strong message that residential and downtown areas should be synonymous to slow driving, illustrated in this production by streetfilms, implementation stateside is not nearly so easy. In Hoboken's version, "Twenty is Plenty", we are campaigning that drivers "consider driving" 5mph slower than the posted 25mph speed limit because this small change in speed has a major impact on the chances of fatality in a pedestrian-vehicle collision. We'd love to enact a lower city-wide speed limit, but we are bound to traffic engineering guidelines that were established when driving a car fast was all that mattered. If drivers agree with the message and choose to slow down, changing the speed limit may eventually come within reach. Will an appeal to sensibilities and safety work as well as a regulatory change?

Hoboken's "Twenty is Plenty" Flyer Makes An Appeal, Not A Rule

Thanks to us (we?) awesome traffic engineers, changing speed limits is not as simple as merely adopting such policy. You can't look at fast cars on a road that has a speed limit of 45mph and just decide that the speed limit should be changed to 35mph. The reason for this is twofold: First, most roads are engineered with a "design speed" that is generally 10mph higher than the anticipated speed limit. In the era of go-fast-twentieth-century-highway-skewed traffic engineering, assuming a faster design speed above an already high speed limit (where "limit" means the fastest one should be legally driving) is unfortunately how things were done. Perhaps this makes sense on highways, but the same rules have traditionally been applied to city streets. To the driver this translates to a road that "feels" safe when driving at or slightly above the posted speed limit, so merely changing the posted speed limit will not change the so-called "perceived risk" of the driver who will continue to drive at the speed that, to him, feels safe. Enforcement addresses this somewhat, but that's an uphill battle.

The second - and more restrictive - reason you can't just come along and change a speed limit is because there are specific traffic engineering guidelines on how a speed limit is changed, and they have absolutely nothing to do with the safety of bicycle riders or pedestrians on that street; instead, they are skewed towards accommodating an assumption that speed limits may sometimes need to be raised. More specifically, if an engineering speed study shows that an appreciable number of drivers regularly exceed the speed limit, a traffic engineer is justified in recommending that the speed limit be lifted. Sure, you can certainly use this same guidance to demonstrate that cars are driving slower, and therefore the speed limit should be lowered, but come on, who are we fooling?

It's certainly a conundrum. So how then do you get vehicles to drive at slower speeds when the gods of traffic engineering have sent you on an upward spiral? We think the answer may be outreach modeled on the UK campaign that does all but establish a new speed limit, at least in the short term. The idea is that if we appeal to the safety aspects of driving slower, and make the case that neighbors and relatives are the people using the same streets we drive on, then perhaps slower driving will become the norm and those pesky engineering studies can be used to eventually seal the deal. It's sneaky, but it could possibly work. What do you think?

Note: New York City recently announced a similar pilot study where they are "testing the feasibility" of lowering speed limits to 20mph on some residential streets. It will be interesting to see how the two parallel efforts, slightly different but with the same objective, pan out.

Maui's Vacation Rental Debate Turns Ugly

Verbal attacks, misinformation campaigns and fistfights plague a high-stakes debate to convert thousands of vacation rentals into long-term housing.

Planetizen Federal Action Tracker

A weekly monitor of how Trump’s orders and actions are impacting planners and planning in America.

Chicago’s Ghost Rails

Just beneath the surface of the modern city lie the remnants of its expansive early 20th-century streetcar system.

Bend, Oregon Zoning Reforms Prioritize Small-Scale Housing

The city altered its zoning code to allow multi-family housing and eliminated parking mandates citywide.

Amtrak Cutting Jobs, Funding to High-Speed Rail

The agency plans to cut 10 percent of its workforce and has confirmed it will not fund new high-speed rail projects.

LA Denies Basic Services to Unhoused Residents

The city has repeatedly failed to respond to requests for trash pickup at encampment sites, and eliminated a program that provided mobile showers and toilets.

Urban Design for Planners 1: Software Tools

This six-course series explores essential urban design concepts using open source software and equips planners with the tools they need to participate fully in the urban design process.

Planning for Universal Design

Learn the tools for implementing Universal Design in planning regulations.

planning NEXT

Appalachian Highlands Housing Partners

Mpact (founded as Rail~Volution)

City of Camden Redevelopment Agency

City of Astoria

City of Portland

City of Laramie